Today we will show you how to draw or animate the human figure walking or running. This drawing lesson is perfect for the person who wants to make an animation of a person walking or running…or for the artist who needs references of walking figures. This tutorial is taken from a book from E.G. Lutz..he was the master of animation before the use of computers.

How to Draw and Animate the Human Figure Walking or Running – Huge Guide and Tutorial

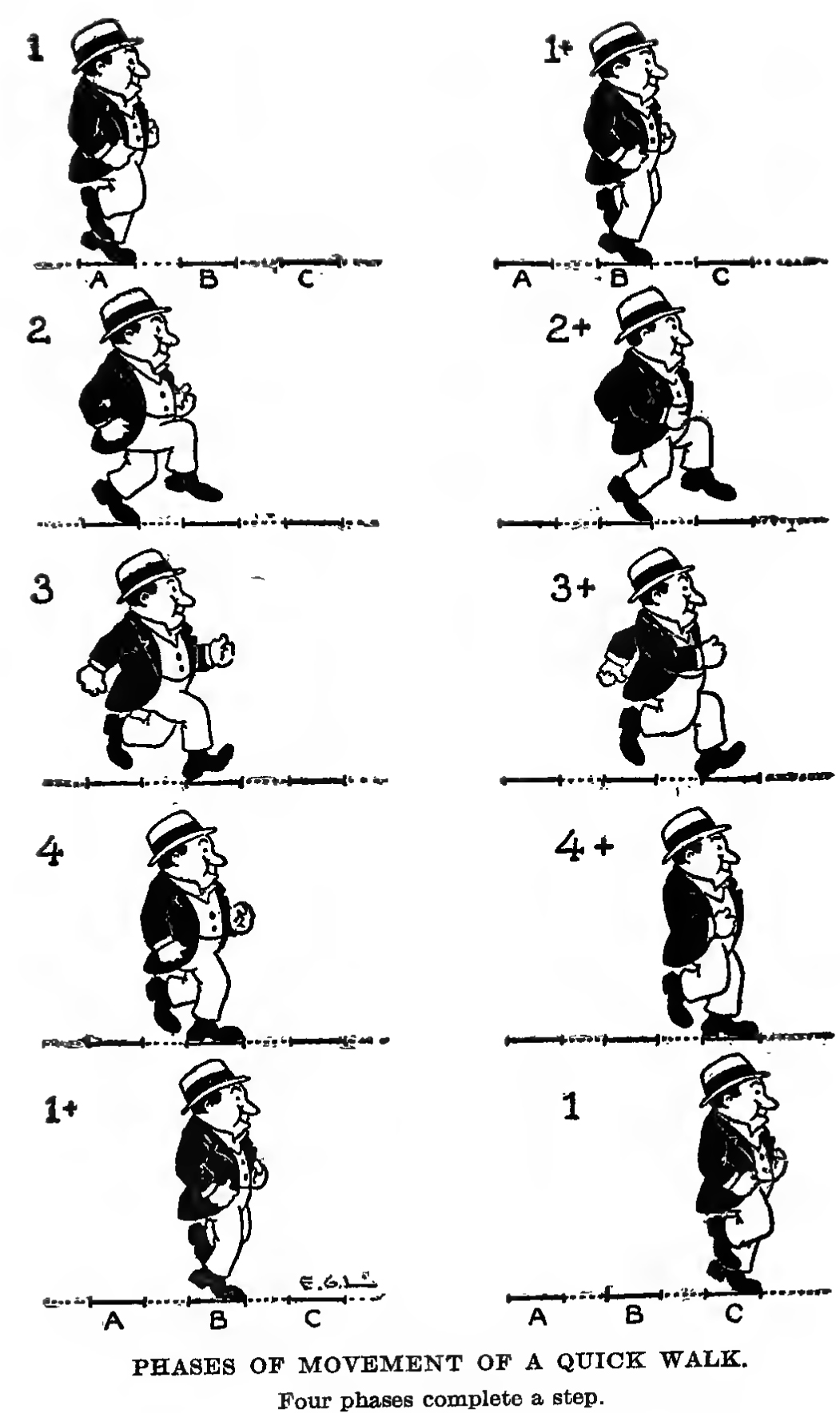

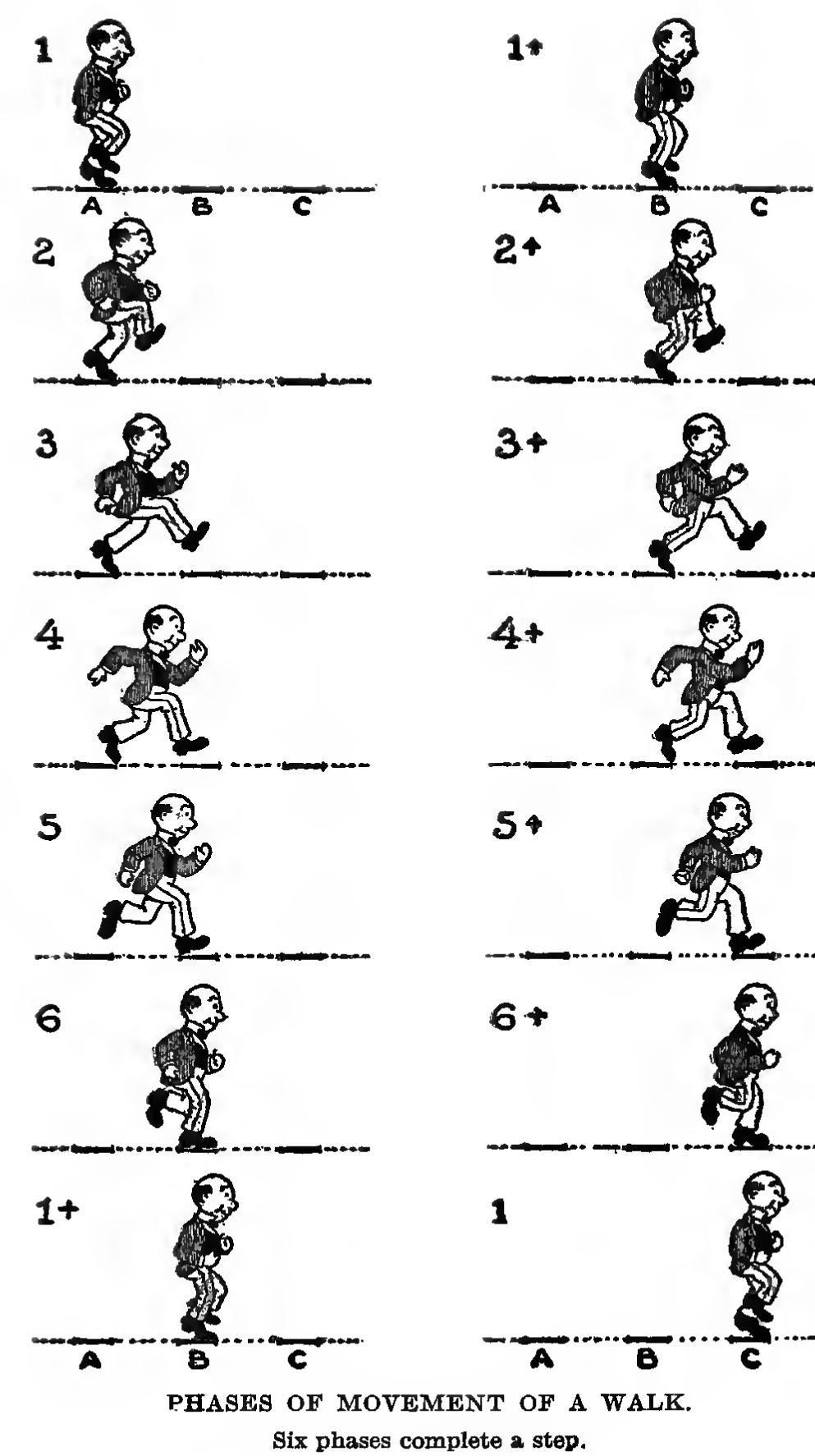

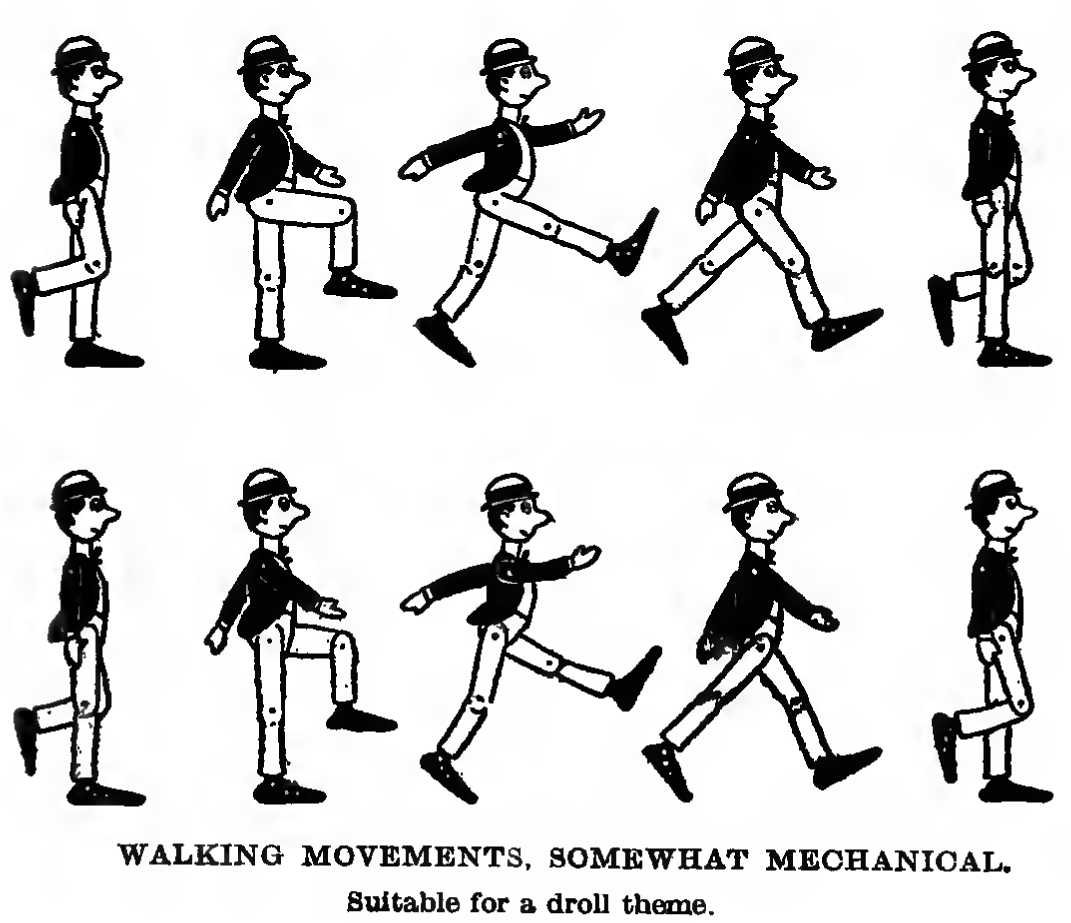

If you want to learn how to animate, one of the first things you will need to learn how to draw is the animated walk. You must become skilled in this before mastering running. The movement of the limbs and torso give the appearance of walking, and you must get it just right to form that illusion. The movement of the lower limbs affects the torso as well as the arms. The arms and shoulders swing is rhythm with the legs to maintain the equilibrium of the person. When you, as an artist, understand the basic facts of the movement of the human figure, you will then be ready to understand the movement of animals as well.

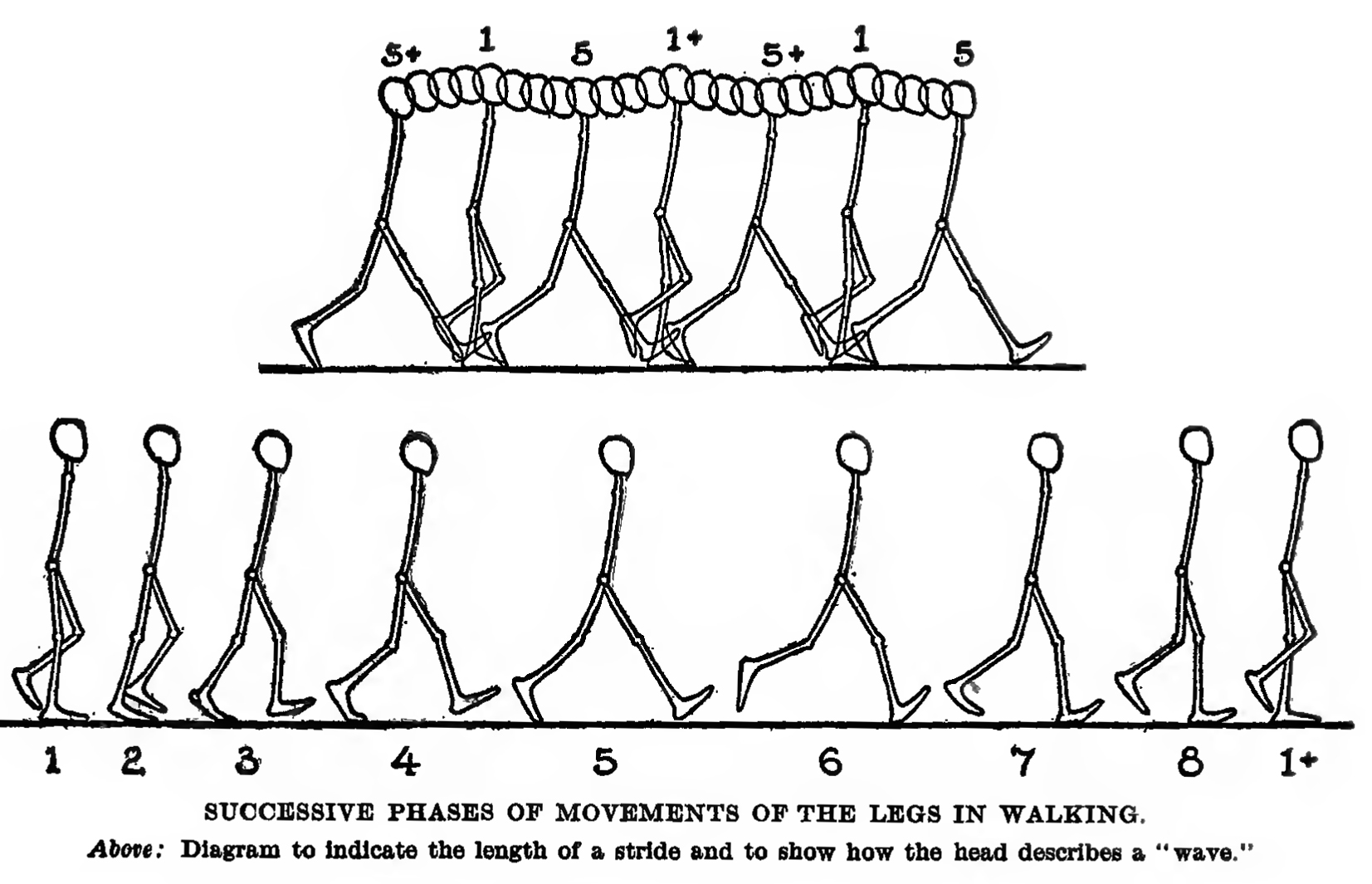

To start, we are just going to focus on the movement of the legs. Imagine now that the person you are drawing is walking. The body in the air, about thirty inches above the ground, is moving forward. Attached to this figure are the legs, alternately swinging and supporting the body in its position above the ground. Further to simplify our study, we will, at first, consider the mechanism of one limb only.

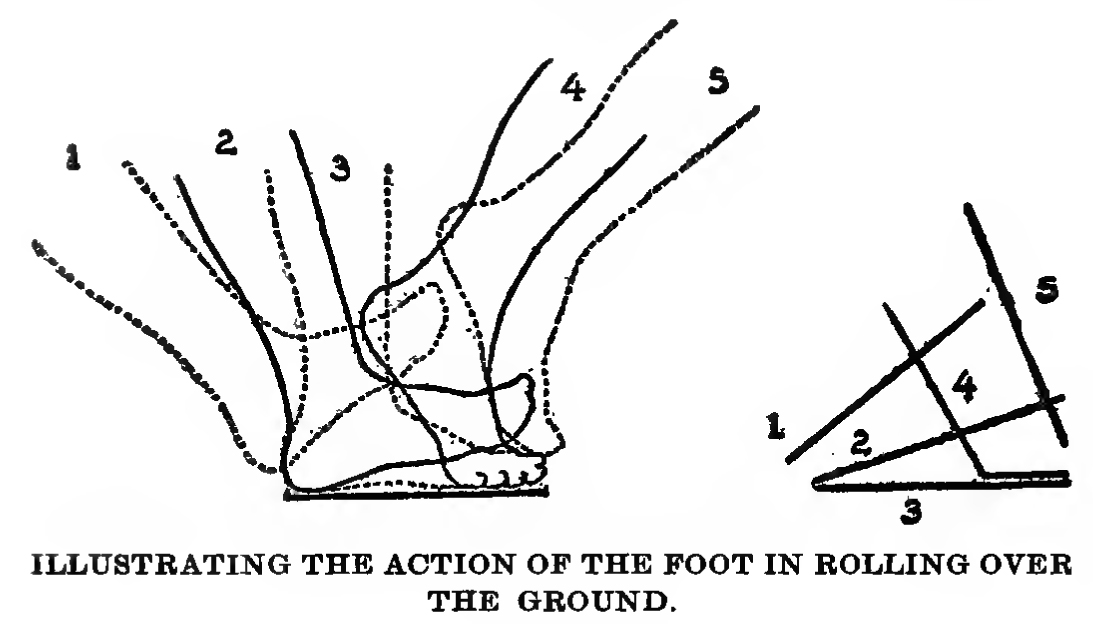

one foot swings forward and reaches a certain place, it seems to hesitate for an instant and then comes down, heel first, on the ground. As the heel strikes, the body is slightly jarred and the oblique line of the limb, its axis, moves and approaches the vertical. In a moment, the limb is vertical as its supports the trunk and the sole of the foot bears on the ground. Then the axis of the leg changes its vertical-ness and leans forward, carrying with it the body. Soon the heel leaves the ground and only the fore part of the foot-the region of the toes-remains on the ground. But before the foot is entirely lifted from the ground, there is a slight pause, almost immeasurable, coming immediately before the foot gives a push, leaves the ground, and projects the body forward.

[ad#draw]

During the time of the phases of movement described above, the foot, in a sort of way, rolls over the ground from heel to toes. Immediately after the toes leave the ground, the knee bends slightly and the limb swings pendulum-like forward, then, as it nears the point directly under the center of the trunk, it bends a little more and lifts the foot to clear the ground. After the limb has passed this central point under the trunk and is beginning to advance, it straightens out ready to plant its heel on the ground again. When it has done so it

has completed the step, and the limb repeats the series of movement phases again for the next step.

Now, the limb of the other side has gone through the same movements, too, but the corresponding phases occurred alternately in point of time. One of these positions of the leg, that when it is bent at the knee so as to clear the ground as it passes from the back to its advancing movement forward, is rarely represented by the graphic artist in his pictures. The aspect of the limbs when they are at their extremes-spread out one

forward and one to the back, is his usual. pictorial symbol for walking. But the position, immediately noted above, is an important phase of movement, as it is during its continuance that the other limb is supporting the body.

A movement of the body in walking can be seen turning from side to side as it swings in rhythm with the upper limbs while they alternately swing forward and backward. It is a movement that animators do not always

think about, since only an accomplished animator can imagine movement clearly enough to recreate it. To describe the movement better we will consider it visually.

We are looking at the walker from the side now and can see the body in profile-exactly in profile. When the walker’s arms are at the middle position. As the near-side arm moves forward we see a slight three-quarter back view of the upper part of the body / torso, then when the arm swings back we see the profile again, and with the arm moving still further back, the corresponding side of the shoulder moves with it and the upper part of

(1) A three-quarter view from the front;

(2) profile;

(3) a three-quarter view from the back, and then carries them back and forth

It gives to person, when slightly exaggerated in a funny cartoon picture, a very funny swaggering gait.

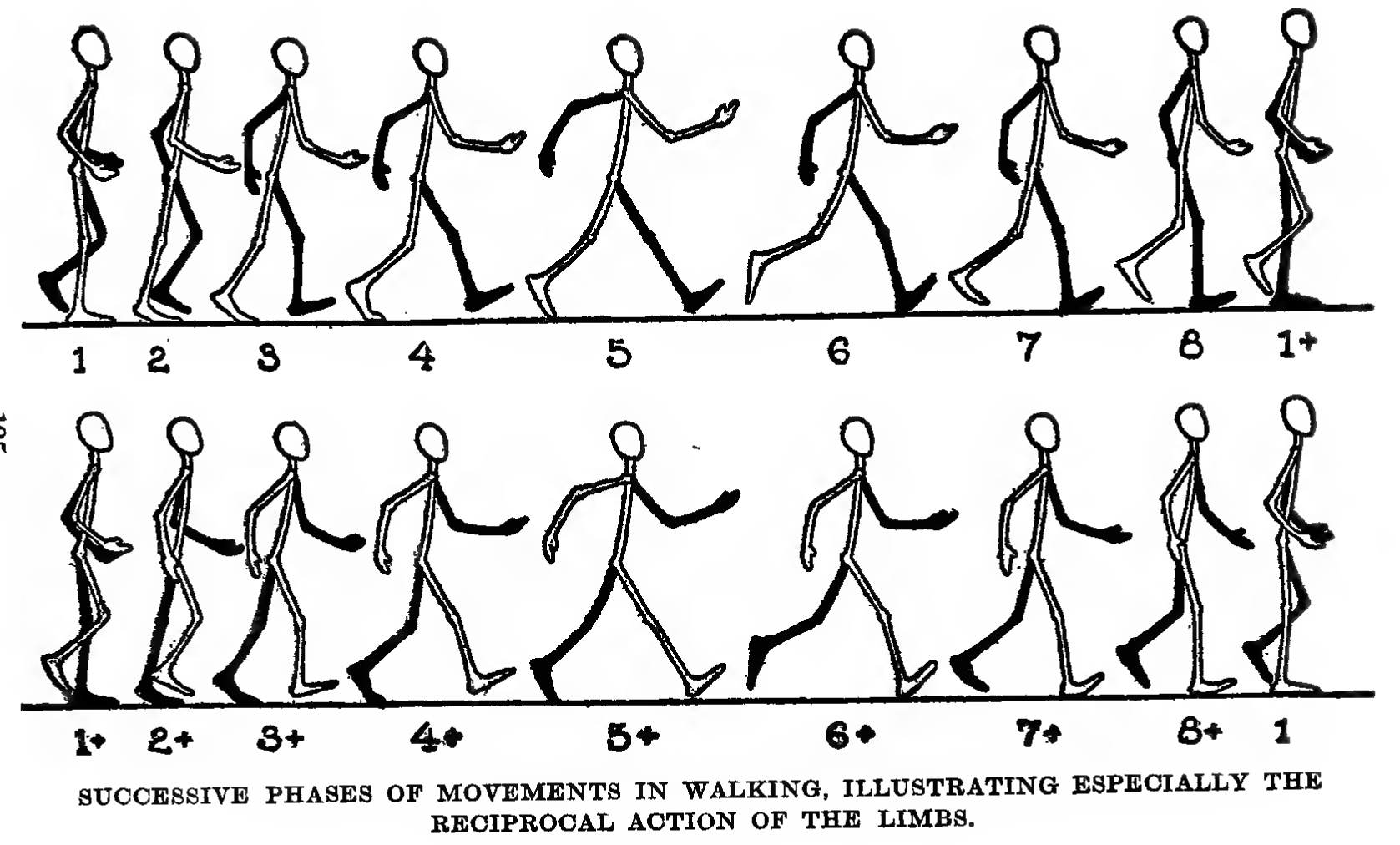

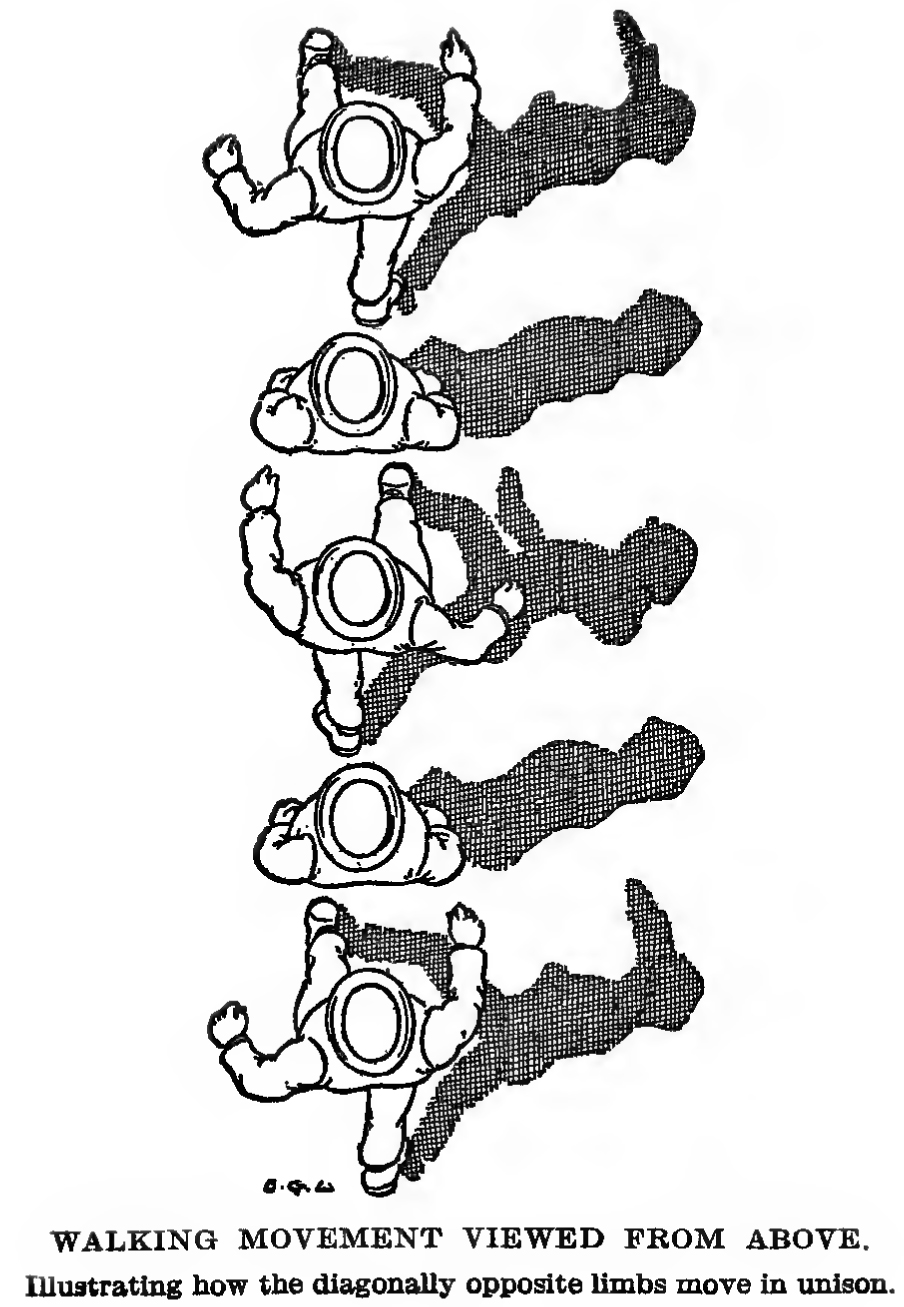

The arms were mentioned as swinging in a walk so as to help maintain the person’s equilibrium.I don’t think you will have a hard time understanding the phases through which they go if you just remembered that an arm moves in unison with the lower limb of the opposite side. This can be seen if you go and look from an upper window down at walkers that are passing by. I want to note that one arm as it hinges and oscillates from the shoulder-joint, follows the lower limb of the opposite side as it hinges and swings from the hip-joint.

Contemplating the arms only, it will be seen that they keep up a constant alternate swinging back and forth. The point where they pass each other will be when they both have approached their respective sides of the torso. This particular moment when the arms are opposite one another and close to the trunk, or at least

near the vertical line of the body, is coincident with the phases of the lower limb movements when one is nearly rigid as it supports the body and the other is at its median phase of the swinging movement.

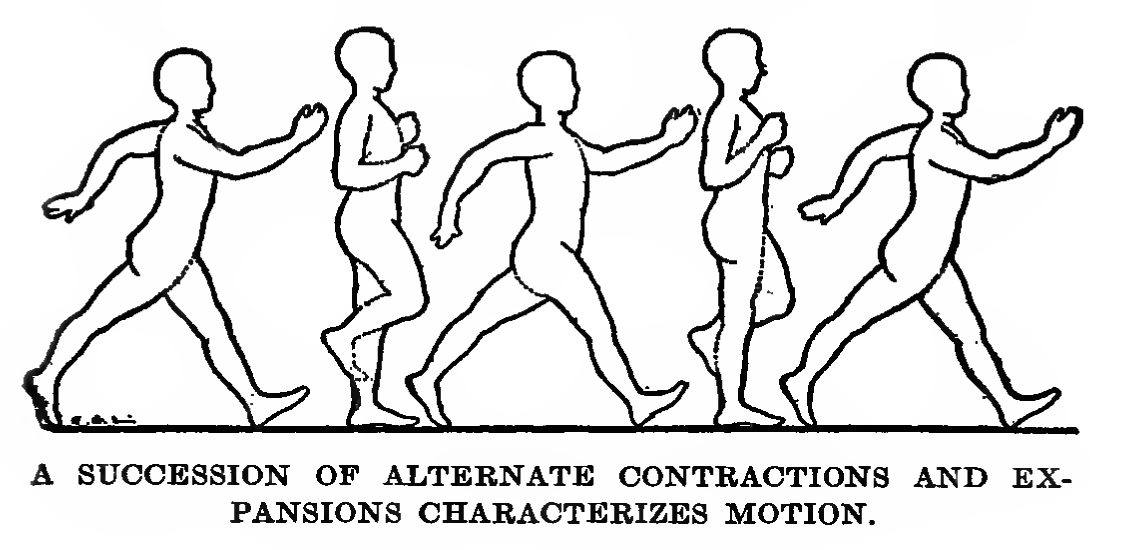

These middle positions of the four limbs-the lower near to each other, and the upper close to the body-is a characteristic that you should take note of and remember. This is a sort of opening movement following by a closing one. These reciprocal changes, expansion and retractions in people and animals, symbolize the activity

of life.

In the human body, for instance, during action, there are certain times when the limbs are close to the torso and at other times when they are stretched out or extended. This is can be plainly seen in the jumping figure. Specifically, this can be seen in the position of the person before the actual jump, the appendicular members bend and lie close to the trunk. The entire body is compact and repressed like a spring. Then when the jump takes place, there is a sudden opening as the limbs flinging themselves outward.

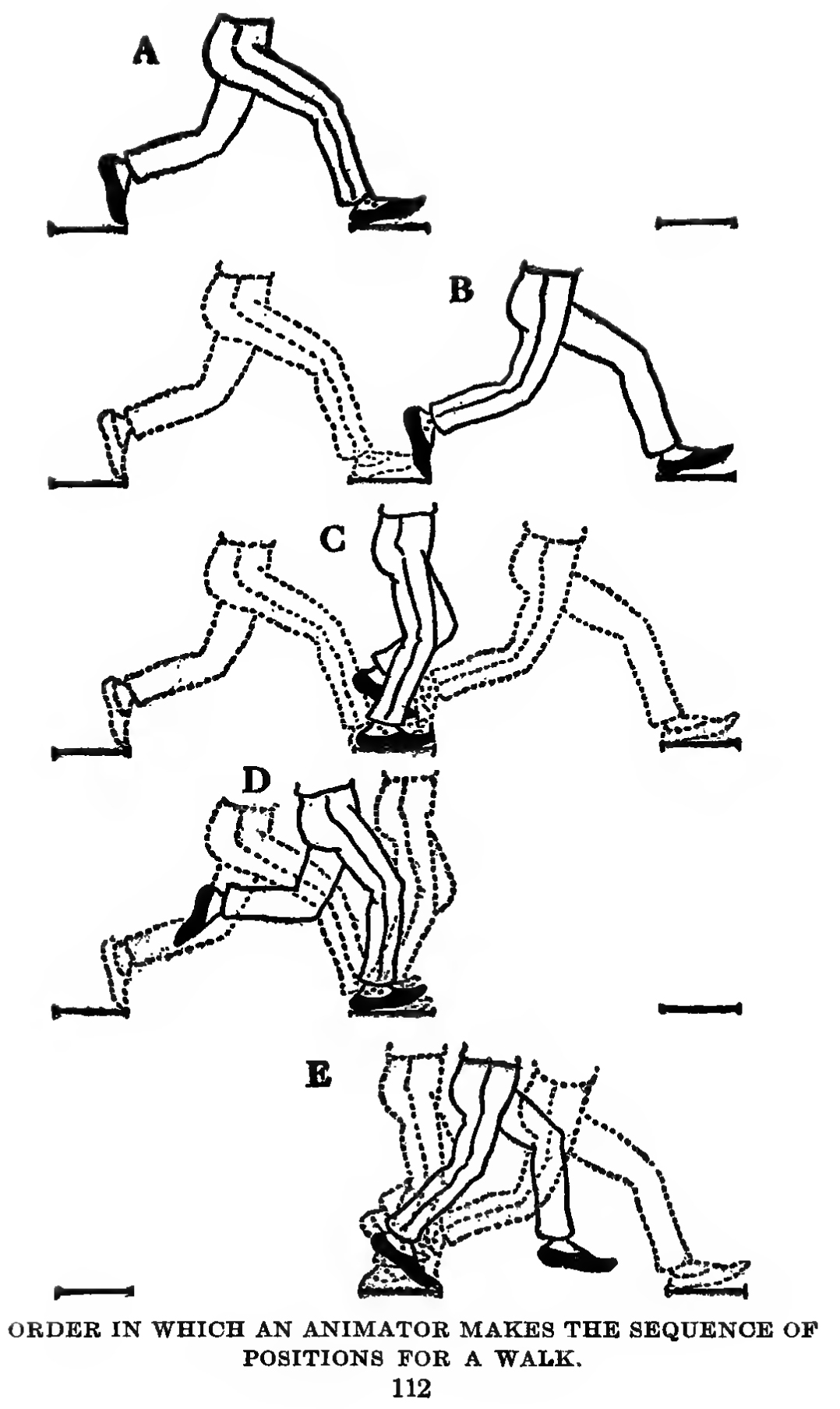

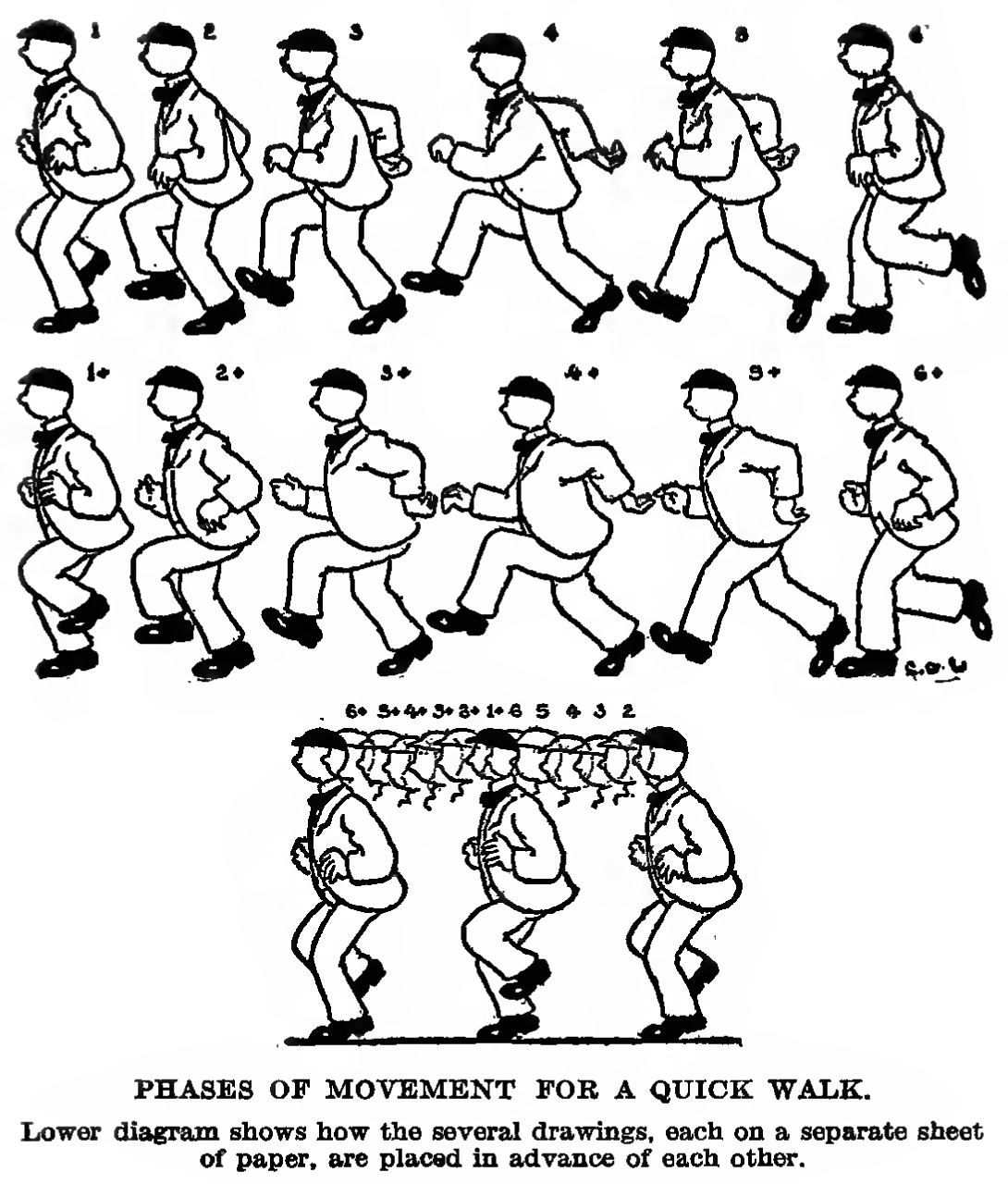

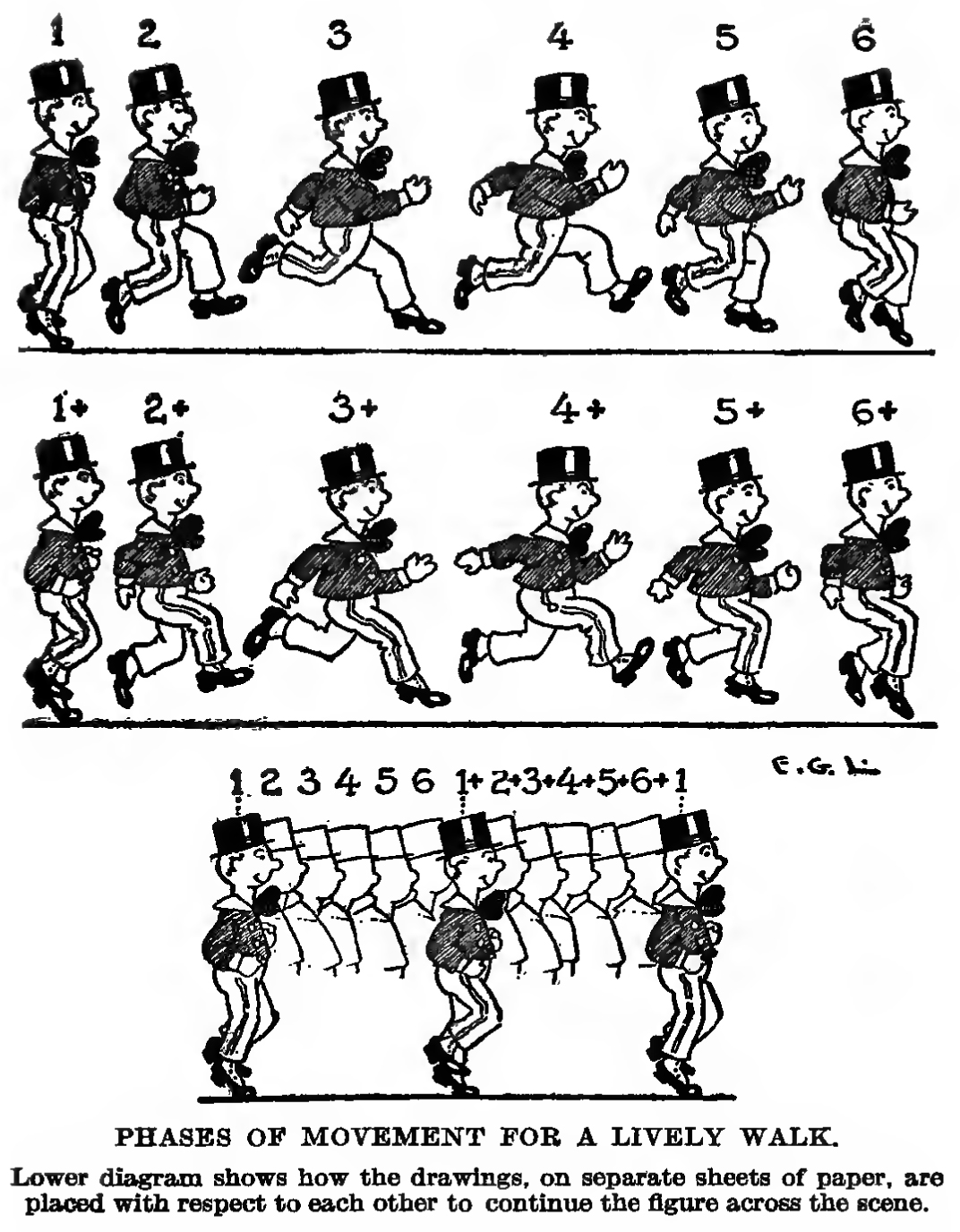

In planning out the positions for a walk, the artist first draws one of the extreme outstretched positions (A). (It is assumed that we are drawing a figure that is going from left to right.) Then on another sheet of paper the following outstretched position (B), but placed one step in advance. These drawings are now placed over the tracing glass of the drawing-board. All the following drawings of this walk are to be traced over this glass, and they will be kept in register by the two pegs in the board. As now placed, the two drawings (A and B) cover the distance of two steps. A foot that is about to fall on the ground and one that is about to leave it meet at a central point. Here a mark is made to indicate a footprint. A similar mark for a footprint is made on each side to show the limits of the two steps.

A sheet of paper is next placed over the two drawings (A and B), and on the central footprint the middle position (C) of the legs is drawn. In this the right limb is nearly straight and supporting the body, while the other limb, the left, is bent at the knee and has the foot raised to clear the ground. The next stage will be to make the· first

in-between position (D) between the first extreme and the middle position. It is made on a fresh sheet of paper placed over those containing the positions just mentioned. The attitude of the right limb in this new position would be that in which it is about to plant its foot on the ground and the left limb is depicted as if ready to swing into the position that it has in the middle one (C).

Then with the middle position (C) and the last extreme one (B) over the glass, on another sheet of paper, the next in-between one (E) is drawn. This shows the right foot leaving the ground and the left leg somewhat forward ready to plant its heel on the ground. We have now secured five phases or positions of a walking movement.

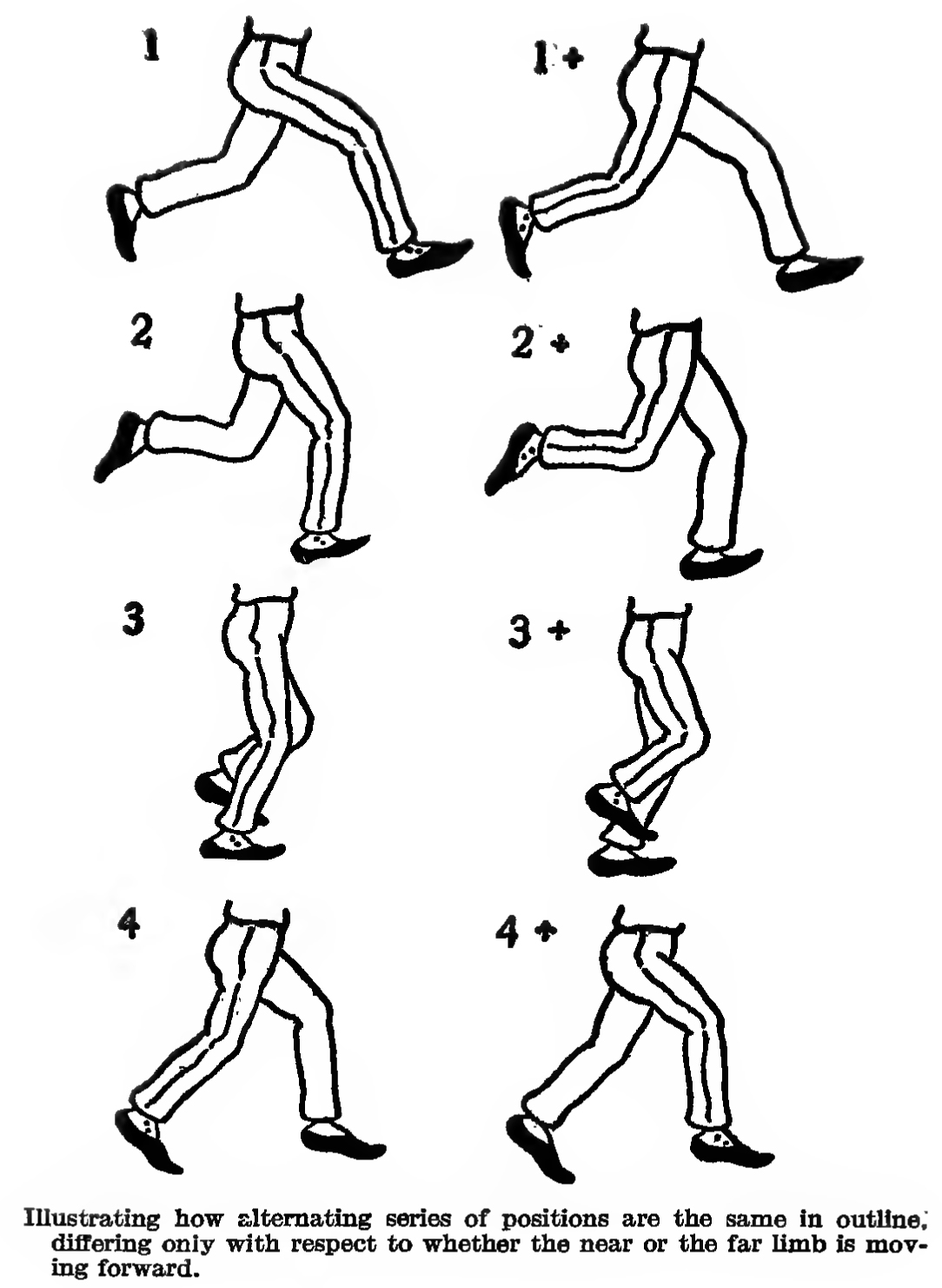

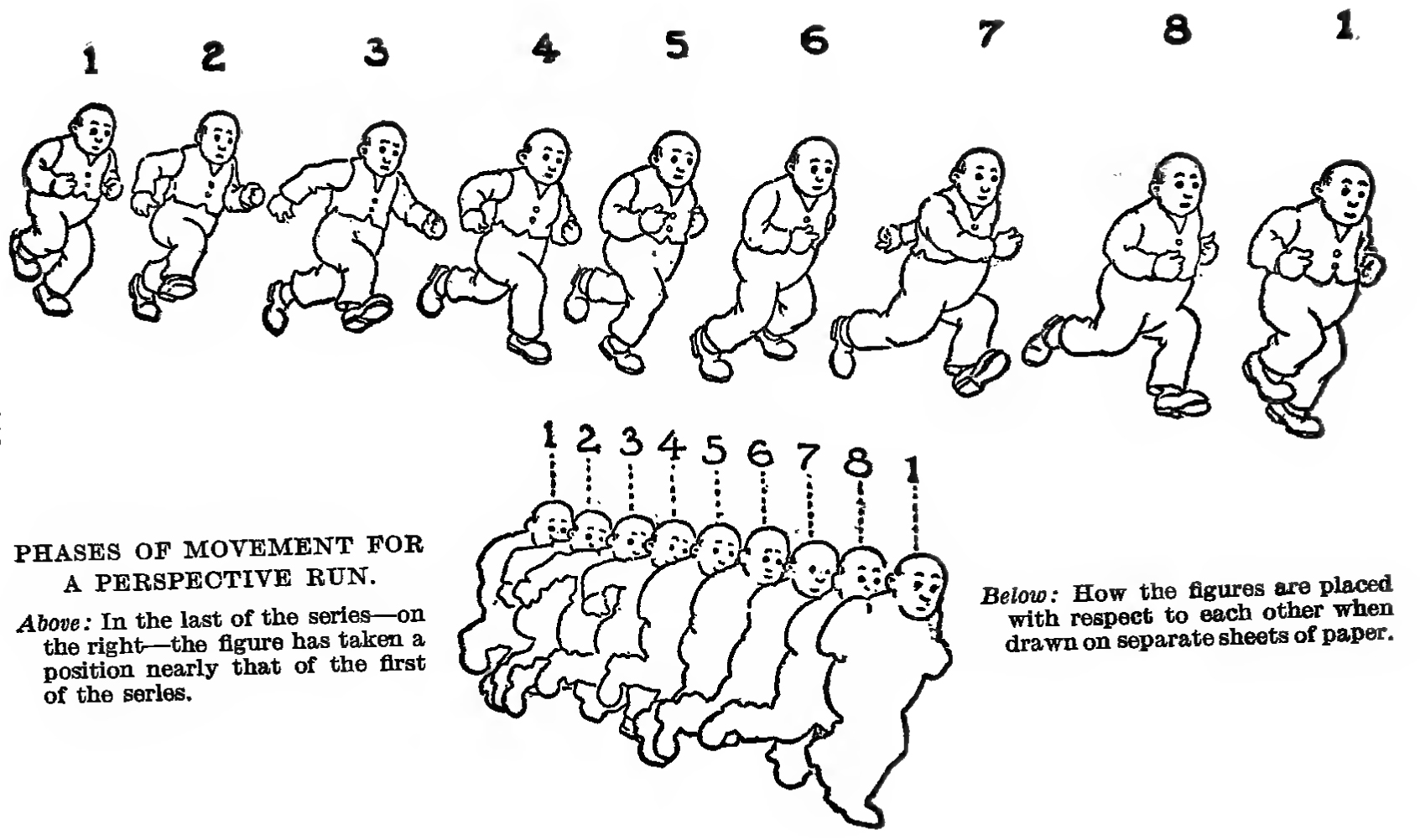

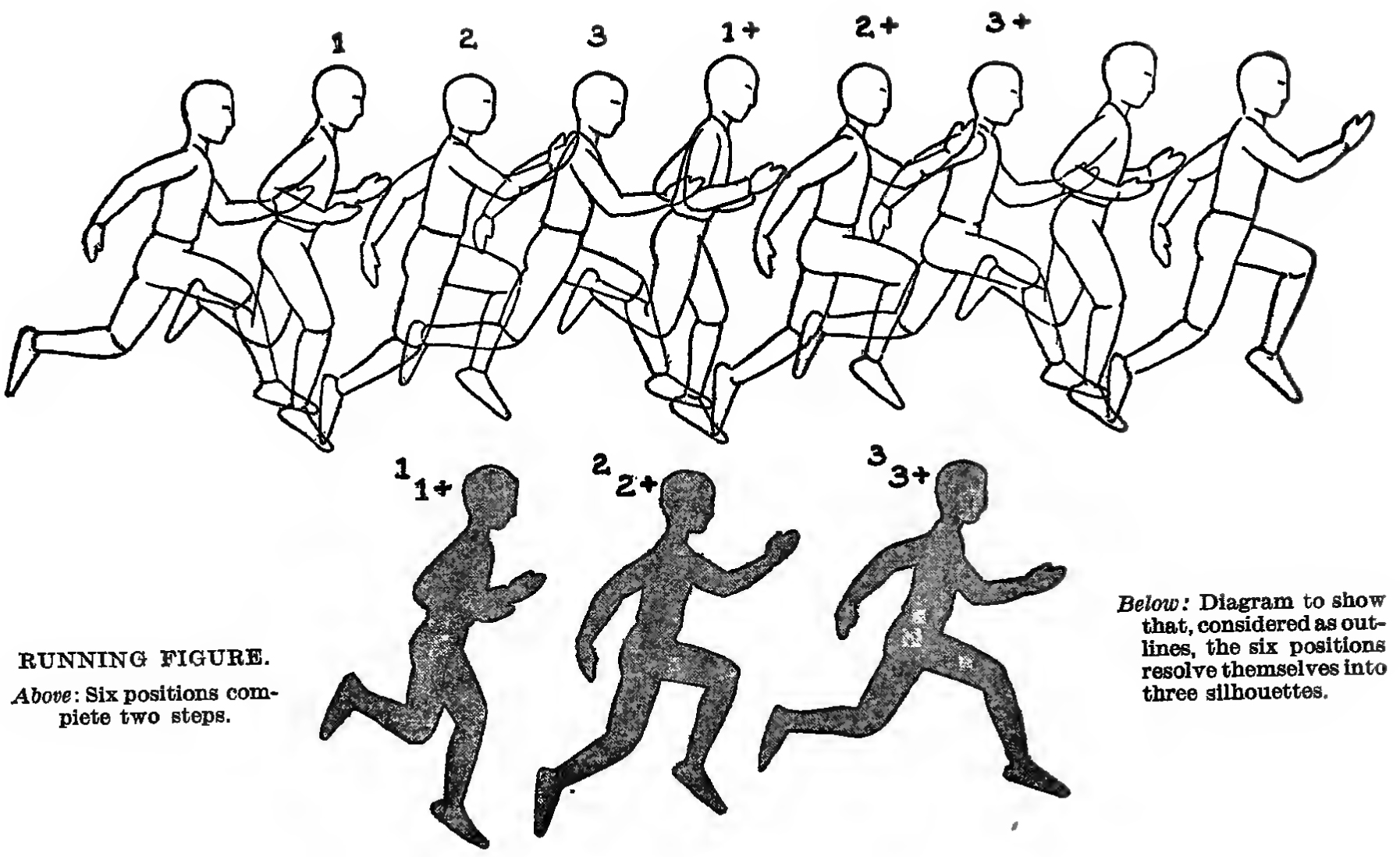

The two extremes (A and B) spoken of as the outstretched ones have the same contours but differ in that in one the right limb is forward, and the left is directed obliquely backward, while in the other it is the left limb that projects forward and the right has an obliquity backward.

Now, if we make tracings, copying the outlines only, of the three other positions (C, D, and E), but reversing the particular aspects of the right and the left limbs, we shall have obtained enough drawings to complete two steps of a walk. As a better understanding of the preceding the fact should be grasped that while one limb, the

right we will say, is assuming a certain position during a step, in the next step it is the turn of the other limb, the left, to assume this particular position. And again in this second step, the right limb takes the corresponding position that the other limb had in the first step. There are always, in a walk, two sets of drawings, used alternately. Any particular silhouette in one set has its identical silhouette in the other set, but the attitudes of the limbs are reversed. To explain by an example: In the drawing of one middle position, the right leg supports the body and the left is flexed, in its coincidental drawing, it is the left that supports the body and the right is flexed. (See 2 and 3+, of the drawing 2 above .. not directly above, but the one before it).

From this it can be seen that the two sets of drawings differ only in the details within their general contours. These details will be such markings as drapery folds, stripes on trousers, indications of the right and the left foot by little items like buttons on boots. Heeding and taking the trouble to mark little details like these add to the

value of a screen image.

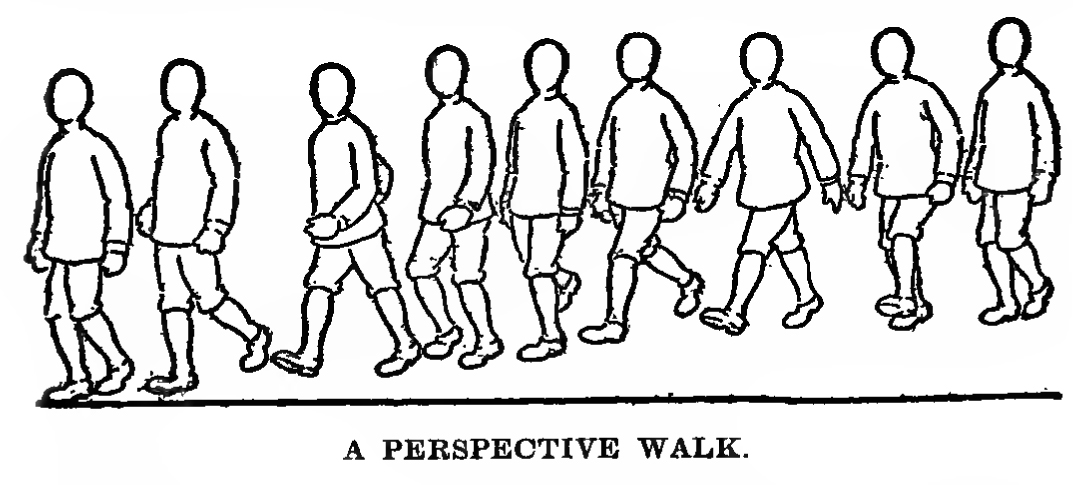

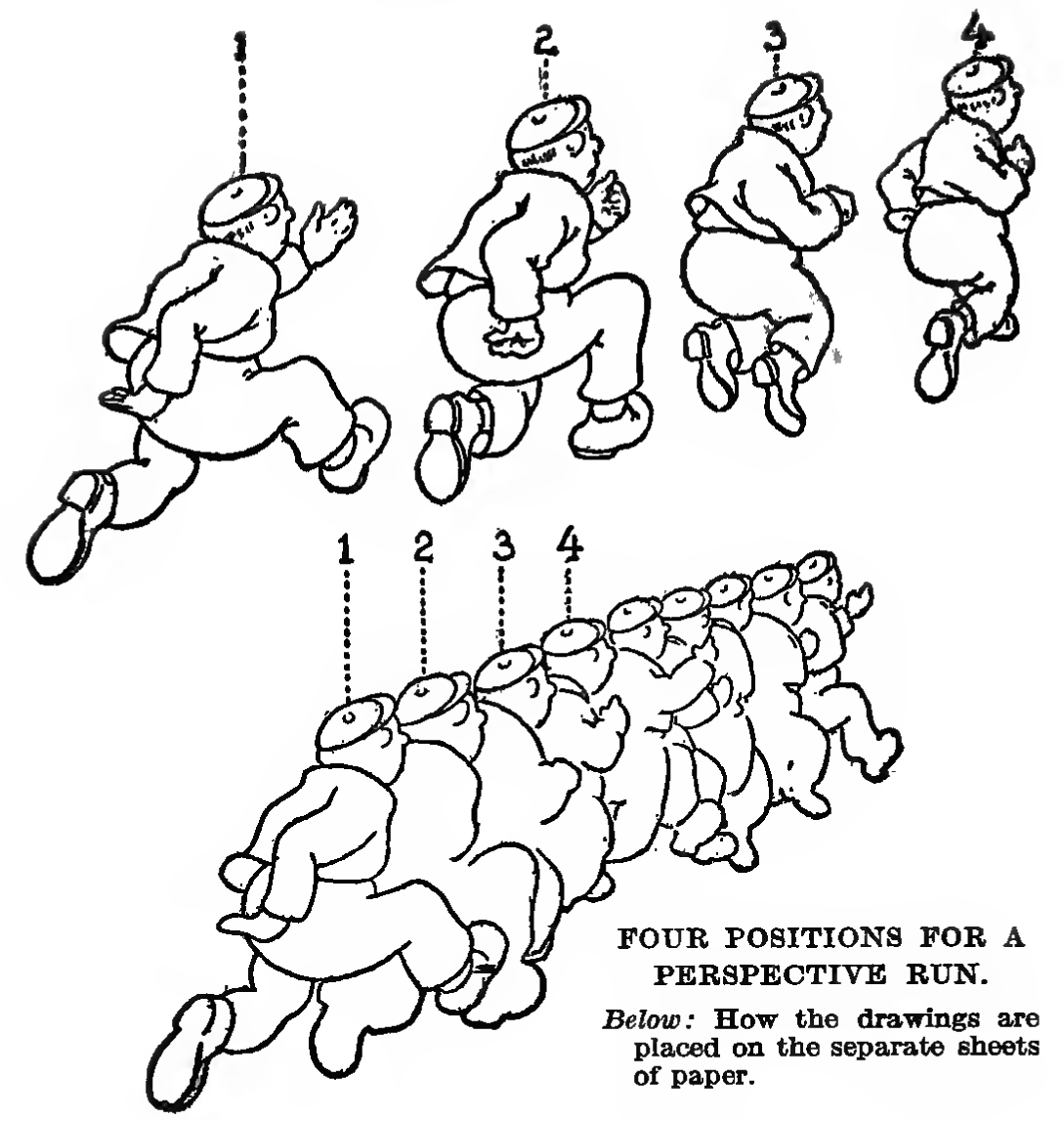

One of the most difficult actions to depict in this art is that which the animator calls a perspective walk. By this term he means a walk in which the figure is either coming diagonally, more or less, toward the front of the picture or going away from it toward the horizon. It is obvious that according to the rules of perspective,

in coming forward the figure gets larger and larger, and in travelling in the opposite direction it gets smaller and smaller. To do this successfully is not easy. Only after a worker has had a great deal of experience in the art is he able to draw such a movement easily.

The constant changing sizes of the figures and getting them within the perspective lines in a graduated series are perplexing enough matters. But this is not all. There is the problem of the foreshortened views as the limbs are beheld perspectively. Imagine, for instance, an arm pointing toward the spectator in a foreshortened view.

Every artist would have his own individual way of drawing this. Those with a natural feeling for form and understanding anatomy solve problems of this kind by methods for which it is impossible to give any recipe. Some would start with preliminary construction lines that have the appearance of columnar solids in perspective, while others scribble and fumble around until they find the outlines that they want.

Happily in most of the occasions when a perspective walk is required in a story it is for some humorous incident. This signifies that it can be made into a speedy action, and that but a few drawings are needed to complete a step.

Artists when they begin to make drawings for screen pictures find a new interest in studying movement. In the study of art the student gives some attention, of course, to this question of movement. Usually, though, the study is not discriminating, nor thorough. But to become skilled in animating involves a thoughtful and analytic

inquiry into the subject. If the artist is a real student of the subject its consideration will be more engrossing than the more or less slight study given to the planning of the single isolated phases, or attitudes, of action in ordinary pictorial work.

A great help in comprehending the nature of movement and grasping the character of the attitudes of active figures are the so-called “analysis of motion” screen pictures. In these the model, generally a muscular. person going through the motions of some gymnastic or athletic activity, is shown moving very much slower than the

movement is in actuality. This is effected by taking the pictures with a camera so constructed that it moves its mechanism many times faster than the normal speed.

The animated drawing artist becomes, through the training of his eye to quick observation and the studying of films of the nature immediately noted above, an expert in depicting the varied and connected attitudes of figures in action. Examples for study on account of the clear-cut definitions of the actions, are the acrobats with

their tumbling and the clowns with their antics.

Then in the performances of the jugglers and in the pranks of the knock-about comedians, the animator finds much to spur him on to creative imagery. The pictorial artist for graphic or easel work, in any of these cases, intending to make an illustration, is content with some representative position that he can grasp visually, or, which is more likely to be the case, the one that is easiest for him to draw. But the animator must have

sharp and quickly observing eyes and be able to comprehend and remember the whole series of phases of a movement.

A fancy dancer, especially, is a rich study. To follow the dancer with his supple joints bending so easily and assuming unexpected poses of body and limbs, requires attentive eyes and a lively mental· photography. The limbs do not seem to bend merely at the articulations and there seems to be a most unnatural twisting of arms, lower limbs, and trunk. But it is all natural. It simply means that there is co-ordination of movement in all parts of the jointed skeletal frame. This co-ordination-and reciprocal action-follows definite laws of motion, and it is the business of the animator to grasp their signification. It is, in the main, the matter already spoken of above;

namely, the alternate action of flexion or a closing, and that of extension or an opening.

With these characteristics there is also observable in the generality of dancing posturing a tendency of an upper limb to follow a lower limb of the opposite side as in the cases of walking and running.

Very strongly is this to be noticed in the nimbleness of an eccentric dancer as he cuts bizarre figures and falls into exaggerated poses. For instance, when a lower limb swings in any particular direction, the opposite arm oscillates in the same direction and brings its hand close enough to touch this concurrently swinging lower

limb.

This symbolical phenomenon of the activity of living things-the negative quality of a closing or flexion, and the positive one of an opening or extension-is not a feature entirely confined to human beings and animals, but is a characteristic showing in the mechanics of many non-living things.

Technorati Tags: walking, running, how to draw people walking, drawing people walking, how to draw people running, drawing people running, animate walking figure, animate walking person, animate running figure