Here is a blurb from an old book that sheds light on how artists use to figure out the correct measurements and proportions of the human body.

Attempts hove been mode ever since Antiquity to submit the proportions of the human body to a formula. In comparatively recent times Durer made on exhaustive study of bodily proportions which is still valid as a point of reference for modern research. Since no two bodies grow to the some proportions, the search must start with on average of many measurements. From this it is relatively simple to find the individual character of a real body. All research on this subject has concluded that the human body is constructed by and large according to the proportions of the golden mean. This proportion is a division of a given distance so that the smaller section stands in the some relation to the larger as the larger does to the whole. The algebraic formula is m:M=M:(m+M); where m=minor, smaller section, M = major, larger section. This division can be exactly found only in a geometric construction, but it yields on approximate figure of 0.618, which serves as multiplier for the value of the distance to be divided. The result gives the value of the larger section with sufficient exactitude.

This theory ought to be understood; though, since calculations and geometric figures or out of place in a freehand drawing, it is enough to judge by eye or to use the simplest measurements, with folded strips of paper or a pencil held out to mark off distances. This technique should be mastered, for it is essential to be able to divide distances. More theory: the Fibonacci series in which each succeeding number is the sum of the two preceding ones yields increasingly close approximations to the golden section:

(1 : 1, 1 : 2) 2 : 3, 3 : 5, 5 : 8, 8 : 13,13 : 21 and so on. It is close enough to stop at the proportion 3:5, according to which 8 ( 3 + 5) con be divided easily according to the golden section . If a length is 176 inches, on eighth is 22 inches (5/8 = 110″ + 3/8 = 66″ ) .

[ad#draw]

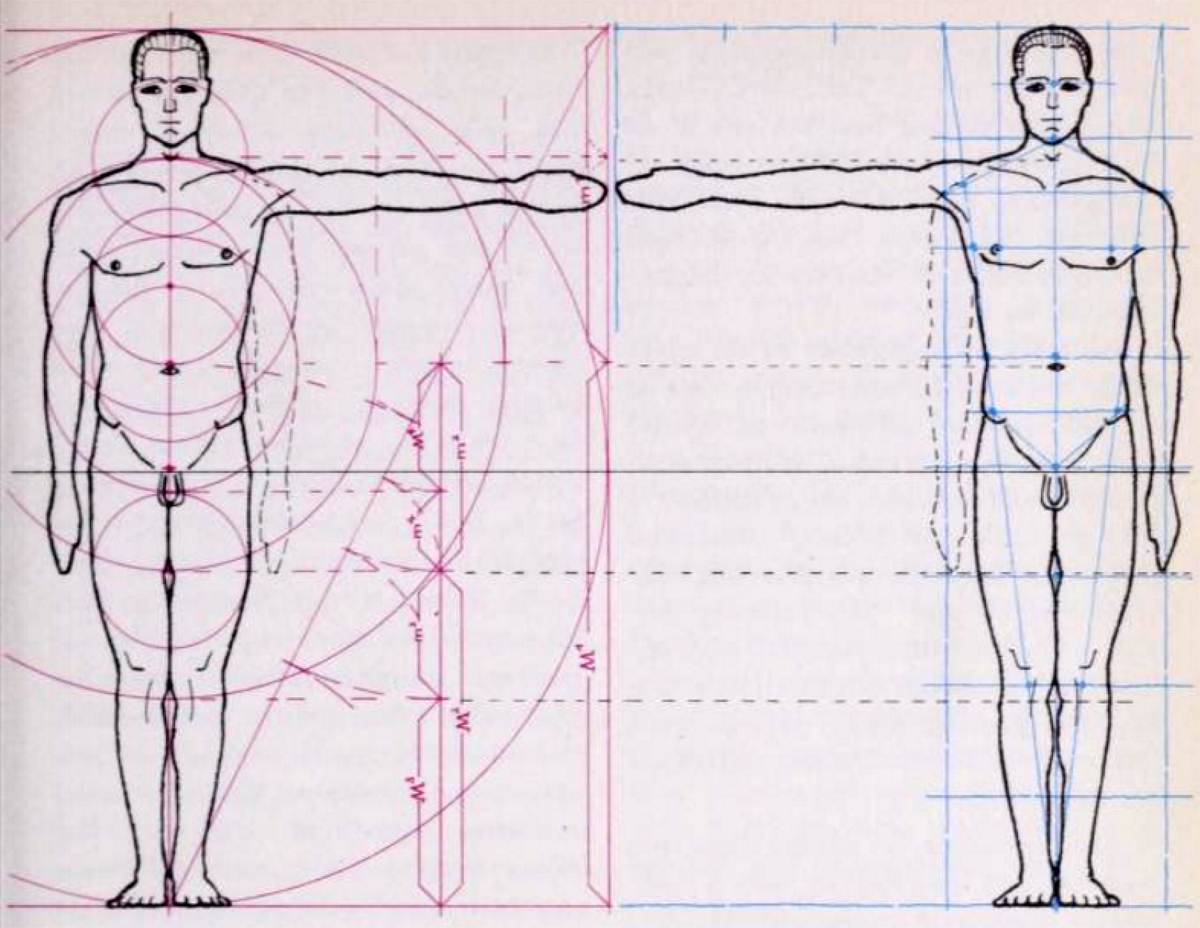

Of course, no figure drawing is started by making a series of measurements. All we need to do is to mark down the height from the standing line to the crown, and then to halve it. These divisions are halved again, and yet again until the height is divided into eighths. The third and fifth sections divide the whole height by golden section. Ever since Antiquity the following rules have been valid: the human head, measured from the under edge of the chin to the top of the crown without hair is on eighth the length of the whole height of the body. The novel is to five-eighths of the height of the body from the ground. If this distance is again divided according to the golden section in a relation of 3:2 it meets important lines of proportion on the shin. The diagrams show how divisions into eighths mark out other important points on the body.

The proportion 3 : 5 is not for advanced in the Lame series and is, therefore, not very exact A multiplication 176 by the index 0.618 arrives at 108.7. This makes a difference from the division into eighths of 1.4. The practical effect is that the navel has to come very slightly lower than the five-eighths line a correction which can be made by eye.

The drawings illustrated side by side show a comparison of the exact and rough schemes, demonstrating that the Iatter is perfectly adequate for freehand drawing The exact scheme con be arrived at only with compass and set square, and these hove no place in on artist ‘s equipment. The difference is so small that a scaffold of 16 squares is perfectly satisfactory It is quite sufficient to draw this scaffold freehand and by eye.

Some other measurements are of use. The two diagonals from the standing point to the corners of the complete double rectangle have been found to launch important points, though they bear no relation to the golden mean…Neither do the two outside lines of a rectangle formed by one-eighth squares on either side of the center axis, but these ore easy to find and give useful indications for the breadth of the body If the upper four squares ore divided into sixteenths, the lines ore valuable for finding the proportions of the head as a basis for the shoulder triangle and for the distance between the breasts another division into sixteenths in the fifth squares will give the triangle of the pelvis. Unlike many other guiding lines this one is not altered by movements of the body, as the pelvis is rigid within its own bone structure. No guiding lines can do more than give points of reference for comparing with the model.

The only generalization to be made about the adult human body, in view of the extraordinary differences of proportions from one individual to another, is that all healthy bodies are consistent: a thickset trunk has thickset head and limbs; short armed people generally hove short legs as well. This harmony persists in the soft port s, too: the musculature, fat and skin tissues. There are, broadly speaking, three general types into which all the multifarious individuals can be divided:

1. The slender type, tall and thin and long-limbed, with a long,

narrow trunk and correspondingly narrow shoulders and a long, narrow skull.

2. The athletic type with broad shoulders, a high solid skull, powerful trunk with large chest, firm abdominal muscles, little fat tissue, making the muscle contours clearly visible attached to large bones. The body has on overall wedge shape.

3. The compact, thickset type, of medium height, with round skull, short

neck, and a deep chest. A tendency to grow fat tissue inclines to make the muscle contours even out; the face is soft and plump and the body paunchy. This type loses its harmonious proportions if, through hunger or diet cures, an attempt is made to approximate it to on irrational ideal.

Fundamental differences between the mole, female, and child’s body structures also exist alongside individual differences. The male body is generally used for the study of anatomy as it shows the bones and muscles most dearly. Male and female differences ore to be explained through their difference in biological function, the mole being more adapted to work and the female to the demands of reproduction-hence, for in stance, the greater breadth of the female pelvis. This in turn causes a strong curve inwards of the upper leg bones, which is why women lend to be knock-kneed.

The pronounced narrowing of the female waist is in part due to the broader pelvis and in port to its stronger turn forward The female rib cage is generally longer, deeper, and narrower than the mole, and more rounded off at the top. The shoulders drop correspondingly lower and tend to be more rounded and sloping; sometimes the neck , too, seems longer and more slender. On the female body the chest muscles are almost completely hidden by the breasts, which very enormously in shape with individuals. There is no biological nor aesthetic norm to be found for them. The canons of earlier limes maintained that on the whole the female body is smaller and gentler, shorter legged and armed, and with proportionately smaller hands and feel. A comparison of earlier representations of the female body, until the later half of the nineteenth century with photographs of modern sportswomen shows plainly how little these canons apply to the over-aged modern woman. Rather do we see now that the proportions of the female body or not so different from those of the male, a reflection of the changed role which women play in social life. Sloping shoulders have become much rarer in women. A long leg is now the ideal of female beauty, and nowadays it is unusual to see such breadth of hip as used to be taken for normal in the old days.

It Is biologically impossible that the skeleton should hove altered so much in a century; the change con be explained only by the social tendencies of the modern age: women now hold themselves more upright and walk with more freedom and self confidence. Muscle tone, influenced by these factors, can disguise much and make the anatomy seem very different from what it really is, implying that there is still some mysterious chameleon-like quality in us that can even alter the shape of our soft tissues.

Sport and Human Anatomy usual for girls as for boys, and thus girls, too, develop their muscles at the expense of the fat tissues. Some medical opinion attributes a tendency to greater stature directly to the influence of sunlight on the body, particularly in early childhood. It can be seen from the diagram of physical growth from birth to maturity how different ports of the body grow at different rates. In linear measurement the head, for example, only increases from between a half and a third, whereas the shin is four times as long in a man as in a newborn baby. All the other parts of the body increase in different proportions within these extremes.

The five stages illustrated are not taken at regular intervals of age. Generally, a person grows most quickly between the fourteenth and sixteenth years, and often reaches full stature during this period. It is clear how important it is to uninhibited movement in sun and air with observe the characteristic proportions a minimum of clothing hove become as when drawing children.

Technorati Tags: human proportions, figure drawing, body measurements, body proportions

Today, I'll show you how to draw a cartoon girl pointing at herself with step-by-step…

Today, I'll show you how to draw a crying cute little cartoon guy who is…

Today, I'll show you how to draw an adorably super-cute cartoon owl on a witch's…

Today I will show you how to draw a super cute baby-version of Winnie The…

Today I'll show you how to draw the famous Pusheen cat from social media, such…

Today I'll show you how to draw this super cute chibi version of Deadpool from…