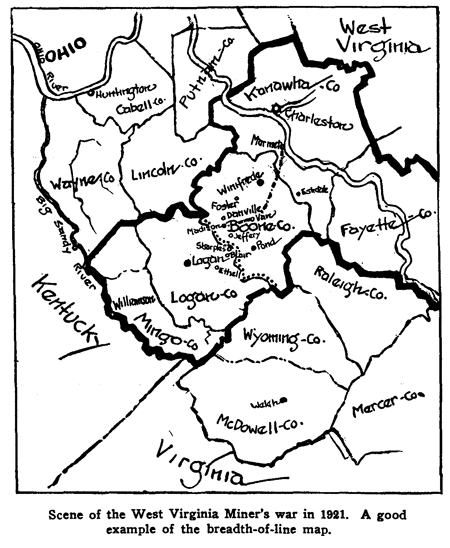

MAKING NEWSPAPER MAPS : Graphic Presentation of Scenes

During wars and conflicts, the staff artist very often has an occasion to be something of a geographic draftsman. Maps were made of the many important moves in the Civil War. These maps lacking colors which are added to maps to distinguish, at a glance, one section of country from another, this extremely useful device had to be suggested by tone or breadth of line in maps for newspaper publication. Now only occasionally will the staff artist have to draw a map. Usually it will be a map relative to the location of a strike zone, or it may be a road map for the automobile section of the newspaper.

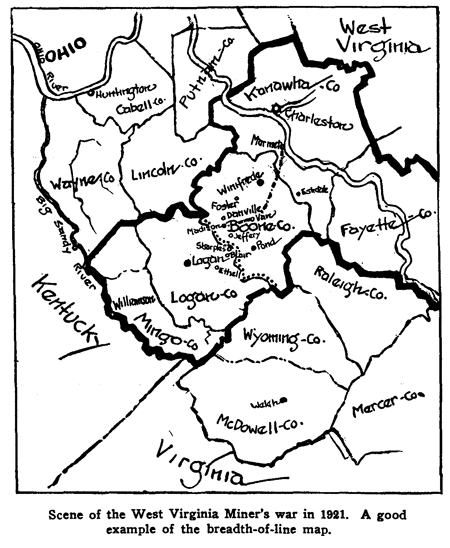

At the top is a map showing those portions of the British Empire which at one time were creating trouble for the US government (obviously, a very old map then). This map will often be of use in case of national distrubances of any kind, or can be used to cover a State and even smaller territories. At the Bottom is a graphic picture indicating the line-up of rival football teams.

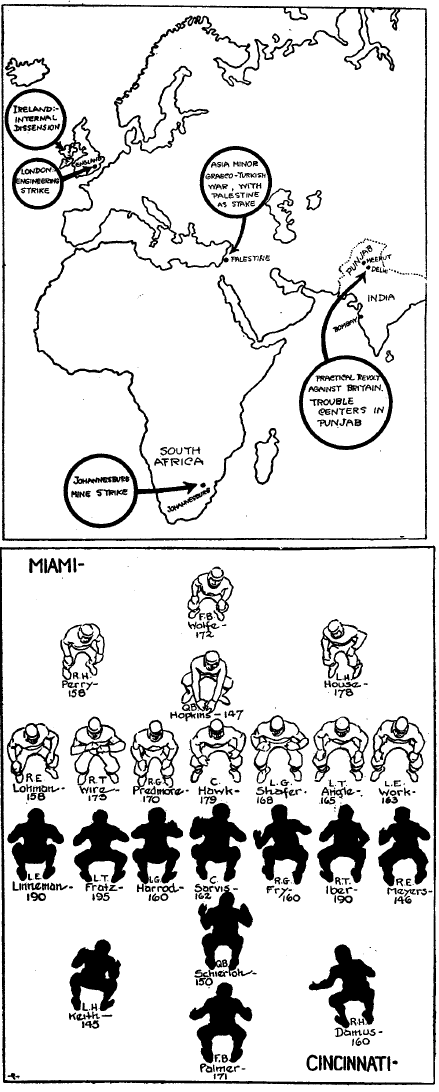

Sketch mapping the scene and the commission of a crime.

On a map wherein you have many cities to place, it is best to define the area by breadth of line. You may add a distinguishing tone, however, lest you confuse it with the lettering and thus hide a few names.

An accompanying plate shows a map of the West Virginia miners' uprising in 1921, and is an example of the breadth-ofline map.

The added advantage of a breadth-ofline map as against one of tone is the fact that the names will stand out most distinctly in the former, whereas they are apt to be lost between the lines in a tone effect.

This map, like most maps, was drawn by tracing over another map (using transparent paper) . What was not wanted and was not essential to the purpose was omitted, giving greater clarity to the value of the map used.

A pantagraph can be used to good advantage for such a purpose. The tracing paper, in this case, was pasted down on a stiff bristol board, then inked. This saves the time and bother involved in re-tracing the map on some paper that would hold a heavy dab of ink without wrinkling.

Note the simplicity and clearness of the British "trouble map."

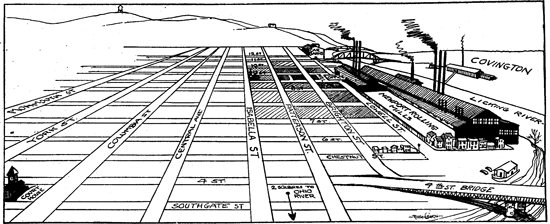

Accompanying this lesson is a map showing the zone covered by the military in a recent industrial war between the Newport, Kentucky, Rolling Mills Company and its striking unskilled labor.

During the latter period of the strike it became imperative for the troops to guard, not only the district about the mill, but also the entire west-end of the city. Therefore the city editor ordered a map showing the area placed under martial law.

To draw this map correctly I journeyed to the scene and from a prominence in the i foreground made a sketch and notes of the scene before me — particularly a view of the mill and the sky-line, the hill in the background, and the first residential block.

Next I obtained a small map of the city (at a drug store), returned to the office, and laid out the drawing by the following method.

Map showing area involved in strike zone. Note the shaded portions to show area under machine gun fire.

Counting up the number of streets across the area and into the scene I roughly placed them in perspective (hard pencil, 3-h.), and added the hills and river. Then I located the mill structure, drew that in (replica of the structure) , also the church, which was struck by bullets, and car barn and bridges. These buildings, being prominent in the news story, gave the readers a series of keys to the location of the land and the distance between them and the mills.

Those structures were blackened to make them stand out.

On the first square opposite, a suggestion is made of the workers' dwellings to suggest that the squares are not vacant areas but lots on which mill workers' homes are located. This is enough, for to fill up the other two blocks would be a waste of energy and tend to distract the reader's attention from the map.

The shaded portions, according to tone, show where the hail of machine gun bullets landed in homes about the mill entrance.

The lettering should be plain and the context very brief. For example, to have added more letters to the numbered streets would have crowded the numbers and made them hard to read. Therefore "4 st" suffices, without the "th" after the "4."

Smoke from the mill was suggested -- darker at the top of the smokestack and fading away. The smoke suggests activity in the plant.

The continuation of the streets beyond the restricter area — it should merely be suggested. The reader, presumably, understands that there is a continuance.

Descriptive maps of murder scenes are similarly handled, substituting the building or scene and human figures. The artist usually visits the scene and constructs his sketch after a tour over the grounds. Or the staff photographer's picture of the scene can be livened up by small action drawings of cross sections of the house, showing important events in the tragedy. These small drawings usually are made in proportion to the photograph, and are pasted thereon, and thus reproduced.

Another method is to trace the photograph onto the bristol board and the action drawings thus made thereon in proper place. The rest of the layout of the house and scene is made solid black, so that the engraver may better note where to strip in the film of the photograph. This process is quite similar to the making of an ordinary layout.

An interesting, graphic manner of showing the line-up of a football team is shown in one of the plates. This is a form of map that is especially effective, as it plainly illustrates the position and the weights, etc., of the players, thus giving the reader a complete, definite idea of the field.

You will find it simplest to make these figures black, with the opposition white. The referee may be put in a gray tone. Silhouettes are easiest to draw. A bit of detail, however, may be put in. This form of map is the best method of showing a particular play and is adapted to practically every sort of game.

Avoid unnecessary details and wording, so that the plays may be observed at the reader's first glance.

CRIME SCENE

An accompanying sketch is of a tragedy — a murder that occurred at night. It is not essential to draw a massed tone to suggest darkness or nightfall in merely a descriptive scene; the text will explain. A suggestion of night suffices, and is quite preferred to losing the descriptive figures by conflict with a mass of darkness.

A passing automobile will give you your model for the back of the car in the picture.

The circle about the bandits suggests the radius of the spotlight and also points them out. This is sufficient to show it is night.

Sometimes an accident or other news event occurs and the city editor decides that a photograph will best show the scene. The photographer is dispatched and returns with a "still" view of the scene, a view that shows the location but is without a suggestion of the action of the event. This is where the artist fits in. The river sketch is a case in point. The story is as follows : a river packet had turned over in midstream with the loss of several lives. The packet was a side-wheel steamer called the "Helper." A picture of a sister ship was found in the "morgue" and from that the details of the ship were noted.

The procedure in making such a drawing is : first obtain the photographer's print of the scene. Place thereon a sheet of paper (tablet paper) which is sufficiently thin to be transparent. To best assure its transparency place the photograph up against the window and lay the drawing paper thereon — you see through it clearly if it is sufficiently transparent. Draw in the scene desired, in proportion and perspective. Next, neatly cut out the drawing and paste it upon the photograph. Draw a line or two connecting the lines, on the paper, with a similar line fading off into the photograph. Draw this line with a greased crayon pencil or wash — a pen will do, but it gives a harder line. Paint in a stroke or more with Chinese white —to serve the same purpose as the line.

The drawing and photograph are now ready for the engraver. He will reproduce the entire composite picture in a half-tone screen.

The same scene could be painted in on the photograph with a wash (lamp black, Chinese white and water mixture)— however the method described above is by far the quickest method and is very satisfactory. And as most such tasks are "rush edition", you will appreciate its advantage.