Home > Directory Home > Drawing Lessons > Sketching Nature > Sketching in Black and White

ART MATERIALS FOR PAINTING, DRAWING AND SKETCHING NATURE INCLUDING PAINTING SUPPLIES AND TOOLS

|

GO BACK TO THE HOME PAGE FOR TUTORIALS FOR BEGINNING ARTISTS

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

MATERIALS AND APPARATUS, INCLUDING PIGMENTS.

Pencils, charcoal, chalk, and etching have been described.

Of paper it is best to use that of Whatman's manufacture only. A very convenient form for water-colour drawing, is Whatman's paper pasted on to millboard or cardboard, and known generally as Cottam's boards. They are rather heavy to carry in large quantities on a journey, but one or two will be both lighter and more convenient to carry when out sketching than either a block or drawing-board. When larger than half imperial size (21 in. by 144- in.), they require some support at the back.

Blocks for small-sized sketches.—When many sketches have to be made, as on a tour, it will be found most useful to have them bound like sketchbooks at one side, so that each leaf as it is detached goes to form part of a book that is complete when the block is finished. Or it might be furnished with a pocket to put the leaves in as each is removed from the others. Blocks without these adjuncts should be exclusively reserved for use in the house.

Whatman's paper is made with four kinds of surface—rough, medium, smooth, and hot-pressed. The first three are known as " Not " paper (i.e. not hot-pressed). Neither the first nor last should ever be used for sketching from nature. The medium quality is the most generally useful. In imperial size Whatman's paper can be obtained in different thicknesses known by numbers that indicate the weight in pounds per ream. Thus "go Not medium," would mean " paper not hot-pressed, medium grain, and weighing go lbs. to the ream." For small blocks this is the most useful weight. Paper as light as 6o is made, but is only suitable for sketch-books.

Again for sizes over 1 imperial, it is as well to use a thicker or heavier paper, such as 140 Not. Large-sized paper is made, called double Elephant and Antiquarian, but these are too large for the convenience of amateurs sketching from nature.

Drawing-boards are best when made with a frame furnished with small points that fasten the paper to the board. The paper should be put on wet, and several sheets may be wetted and stretched together. When everything is dry the positions of these sheets may be easily interchanged, so that several drawings may be carried about on the same board, and each one worked on at pleasure. It is always best to use the thickest paper with these boards.

Canvas is made of all widths and qualities. For sketching use single prime of a pale greyish hue, as the glare of the white canvas out of doors is very disturbing to the eye. It is better for the canvas to be smooth in surface, and not to show its texture through the work, yet it should not be so smooth that the paint does not "bite" easily. Like paper, a rough-surface canvas marks the work to a certain extent, and makes the pupil think his work is better than it is. The texture should be given by the work.

Paper for oil-painting can also be bought, and is very useful for sketches and studies made for a purpose to which no permanent value is attached. The form of tablet for oil-painting called "Academy board" is seldom made of a larger size than " Royal " (22 in. by 19 in.), and is extremely convenient to carry for small paintings. It is pleasant to work upon, but it is only suitable for the slightest sketches, and the colour should be used without varnishes, maguilp, or other mediums, otherwise cracks invariably occur in the sketch that after a time go right through the priming of the board.

Brushes of small size for water colours are best made of yellow sable set in tin with black handles. Of large size it is scarcely worth while to have them of sable, camel's hair being more easy to handle and far cheaper. Everything should be of the best quality ; it never pays in the long run to buy a cheap brush.

For oils, hog-hair brushes should be bought in abundance, and only a few sable, and these of small size. It is as well to have a few very small sable brushes with very long hair for painting reeds, grass, etc.

A really good Sketching Easel is a thing yet to be invented. It should be light, strong, steady in a wind, and adapt itself easily to uneven ground. The most generally useful is the French easel with sliding legs. Its only drawback is that, on account of its lightness, it is not very steady in a wind. It is perhaps more convenient to place than most others, and certainly takes a shorter time to put up. All easels should be sufficiently large to enable the painter to work at them standing. Often five minute's work at a sketch in a standing position, for correcting the drawing and tone, is worth a whole morning's work when sitting.

What is known as the " hook " easel is very convenient for oil-painting, where the three legs consist of poles that pass through brass eyes that are fixed to the frame of the canvas itself. Many artists prefer this to all other systems, and it certainly has the merit of great simplicity, though the picture cannot be raised and lowered as easily as with the French sketching easel.

A Sketching Umbrella in sunny weather, and where the shadow of a wall or some opaque object is not attainable, is a perfect necessity. It should always be lined with some dark colour, so as to make it quite opaque, otherwise it is worse than useless.

The usual semi-transparent brown holland umbrellas should be studiously avoided, as the glare that passes through them on to the paper or canvas entirely precludes the possibility of seeing the tone of the work in the picture.

Tents are made in many forms, but all are comparatively useless, the trouble of taking them to the spot, putting them up, and then afterwards removing them, is too great for artists engaged in sketching from nature, even if there was not the difficulty (before touched upon) of lighting the drawing inside the tent.

Sketching Stools are made in great variety. The best to sit upon is the ordinary camp-stool, but the easiest to carry is the three-legged stool which folds into a stick that can be strapped to the easel. The seats of these stools are scarcely ever made strong enough, and it is best to have one made of leather by a saddler, or else carry a spare seat or two.

There is a combination of easel and stool that is much used by some people. It has the great drawback, however, of fixing the artist at one level and one distance from his work, and hence cannot be recommended.

Pigments are the most important materials in sketching in colours. Although there is an immense variety of them, comparatively few can be here recommended. Use as few as possible, and the best work generally results. The permanency of colours is a subject that has been but too little studied until lately. It was the serious fading of many of Turner's works (especially in water- colours) that awakened the general public, and particularly artists, to a sense of the importance of learning what colours were permanent and what were fleeting.

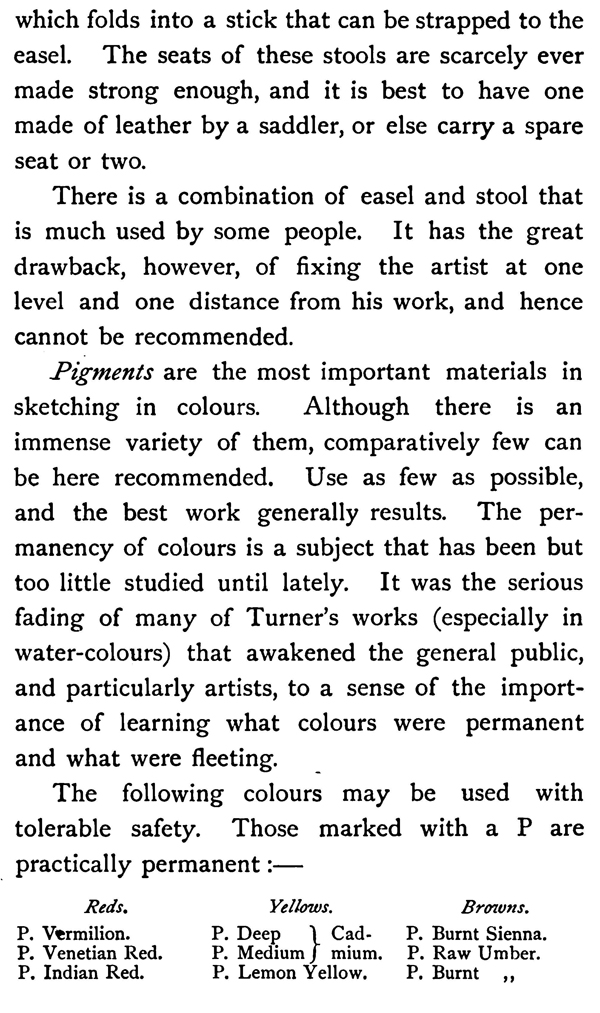

The following colours may be used with tolerable safety. Those marked with a P are practically permanent :—

Reds. Yellows. Browns.

P. Vermilion. P. Deep 1 Cad- P. Burnt Sienna.

P. Venetian Red. P. Medium f mium. P. Raw Umber.

P. Indian Red. P. Lemon Yellow. P. Burnt „

Reds. Yellows. Browns.

P. Light Red. P. Aureolin. P. Sepia.

P. Carmine Madder. P. Yellow Ochre. P. Vandyke Brown.

P. Rose„ Sienna. P. Lamp Black.

Crimson Lae. P. Naples Yellow. P. Purple Madder.

P. Strontium. P. Brown „

P. Cologne Earth. P. Mummy.

Greens. Blues. Whites.

P. Cobalt Green. P. Real Ultramarine. Flake White. P. Zinc

P. Malachite Green. P. French „ P. Chinese „ Bismuth „

P. Green Oxide of P. Cobalt.

Chromium. P. Ultramarine Ash.

P. Cerulium.

Antwerp Blue.

It will be observed how very few greens are here put down though so many are manufactured. Most of them are very fleeting and unnecessary, as nearly all greens that are required in painting can best be made by the mixture of blue and yellow.

In the list of reds one of the most beautiful, viz. carmine, is left out. It is about the most fleeting of all colours, and should never be used. Carmine madder takes its place sufficiently. Crimson lake is not fleeting, but is liable to turn dark, and hence should only be used where such a change is not of much consequence, as in shadows.

Of the yellows the well-known gamboge and Indian yellow are absent. They are both very fleeting colours, the latter especially, and should never be employed. Lemon yellow is not a very permanent colour, though very nearly so when mixed with others. It is only slightly fleeting, but its whole colour never goes, so it is much used, especially as it is the most delicate and useful yellow we possess.

The browns call for no special remark, except that there is a great deal too many varieties of them.

Of the blues, we have omitted the useful indigo and strong brilliant-coloured Prussian. Neither of these should ever be used ; they both turn rapidly black, and the former finally fades. Antwerp blue can generally be made to take the place of these, but should be used sparingly, as it fades slightly. It is also dangerous to mix with the cadmiums or Naples yellow, as the mixture turns black. Real ultramarine is the only perfectly permanent blue, but it is too expensive for ordinary use. The French blue can be employed instead, and is practically permanent, though it fades slightly in course of time. Cobalt, the most useful blue in distances, has a slight tendency to turn green after a long time, especially in oil-colours.

Of whites, the most useful for oils is, without doubt, flake white, though when exposed to the air it turns gradually black. This can be prevented in oil-colours by varnishing, but it is quite useless in water-colours. Zinc white is the only perfectly permanent white, but it is so thin that it is very difficult to handle. The densest is made by Windsor and Newton, but even then it is unpleasant to paint with. Chinese white, the water-colour preparation of the same material, is most useful, and it is quite safe when properly employed. Bismuth white is scarcely ever used.

Of mediums, use as little as possible. It is necessary to rub some drying oil over a first painting before the second is applied, but it should always be cleaned off as much as possible. If we want to thin the colour for fine sable brushes, when putting in small branches of trees, foreground, rushes, etc., a little amber or copal varnish thinned with oil of lavender makes an excellent medium. This may be also used in those places where quick drying is required. Pure copal varnish is liable to crack, and mastic should not be employed except to varnish a picture after it is dry, as, if laid on before, it will rapidly make the picture turn yellow. In fact all mediums except turpentine have a tendency to turn oil-paintings yellow and finally brown or black through the oxidation of the air. Turpentine dries off completely, and if the pigments were ground with this instead of with oil they would be permanent in colour, but would have no cohesive strength. It has also the disadvantage of bringing the different pigments when mixed into such close juxtaposition that chemical action is set up, and the colours alter or destroy each other. The same pigments, when mixed with linseed oil, have no tendency to act in this way. The object of varnishing is to keep out the air, as it is the active agent of destruction. This is best done about a year after painting, when the picture is dry, first covering it over with a very thin coating of copal varnish. In about a week cover again thickly with mastic. The copal will not crack when thus protected from the air. When the mastic is dirty or yellowed it can easily be cleaned off with spirit, the thin film of copal completely protecting the picture from being cleaned away in the process.

Privacy Policy ..... Contact Us