DRAWING CLOUDS, WATER, AND REFLECTIONS

CLOUDS, WATER, AND REFLECTIONS

T. most sketchers clouds are the most fascinating and the most tantalizing part of his subject. At one moment they may

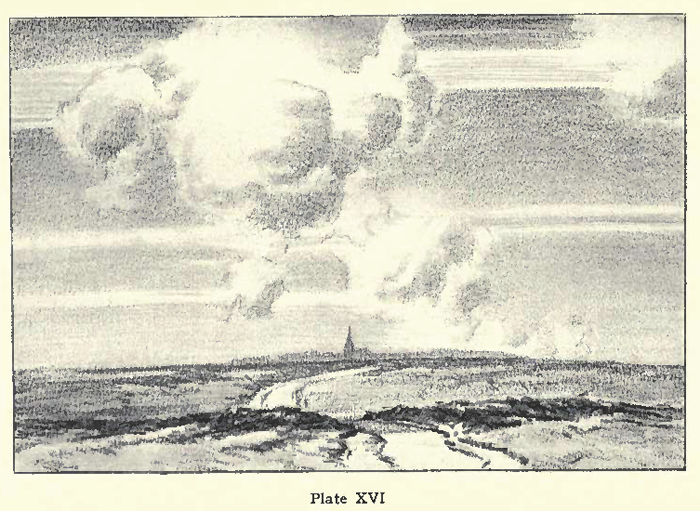

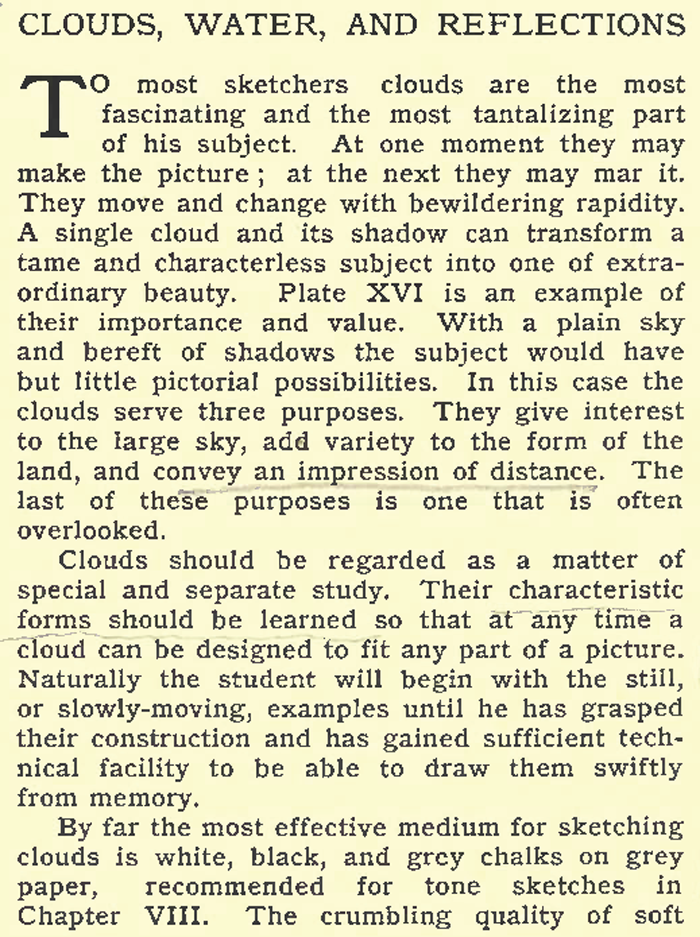

make the picture ; at the next they may mar it. They move and change with bewildering rapidity. A single cloud and its shadow can transform a tame and characterless subject into one of extraordinary beauty. Plate XVI is an example of their importance and value. With a plain sky and bereft of shadows the subject would have but little pictorial possibilities. In this case the clouds serve three purposes. They give interest to the large sky, add variety to the form of the land, and convey an impression of distance. The last of these purposes is one that is often overlooked.

Clouds should be regarded as a matter of special and separate study. Their characteristic forms should be learned so that at any time a cloud can be designed to fit any part of a picture. Naturally the student will begin with the still, or slowly-moving, examples until he has grasped their construction and has gained sufficient technical facility to be able to draw them swiftly from memory.

By far the most effective medium for sketching clouds is white, black, and grey chalks on grey paper, recommended for tone sketches in Chapter VIII. The crumbling quality of soft

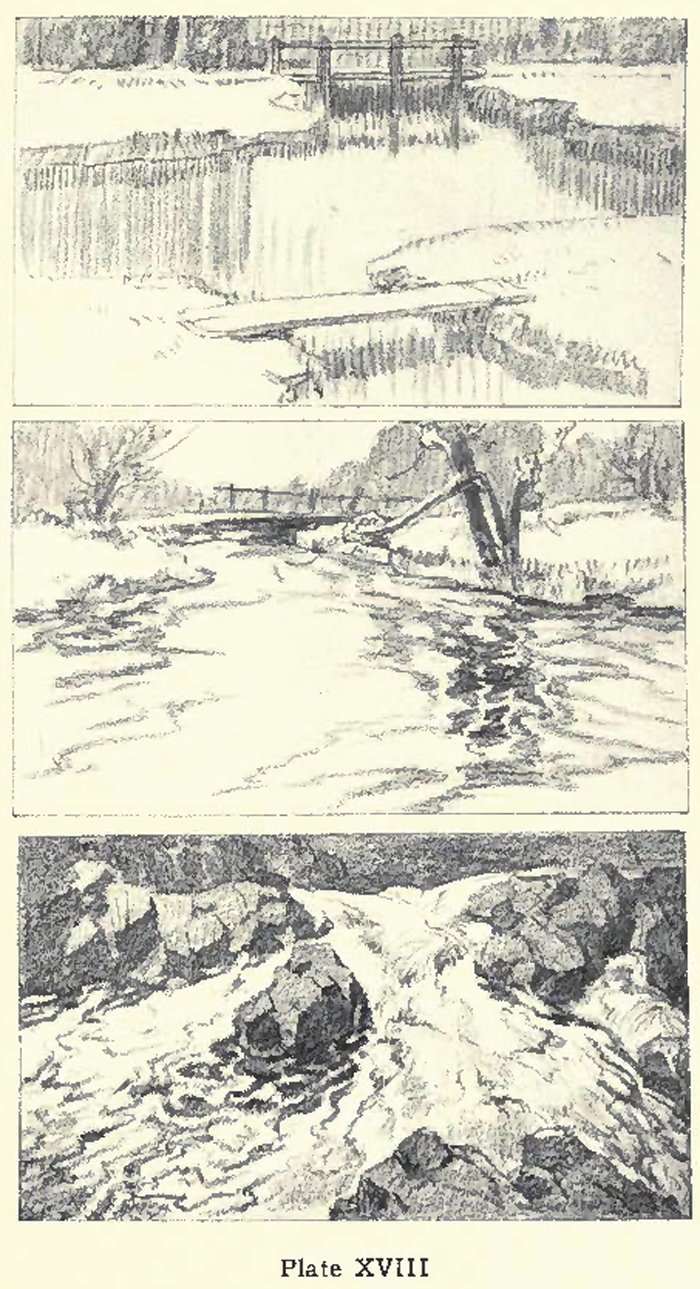

Plate XV I I I

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Plate X I X

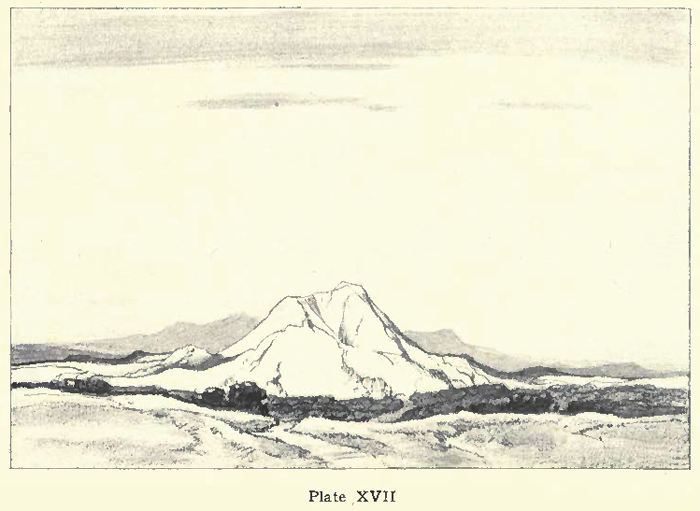

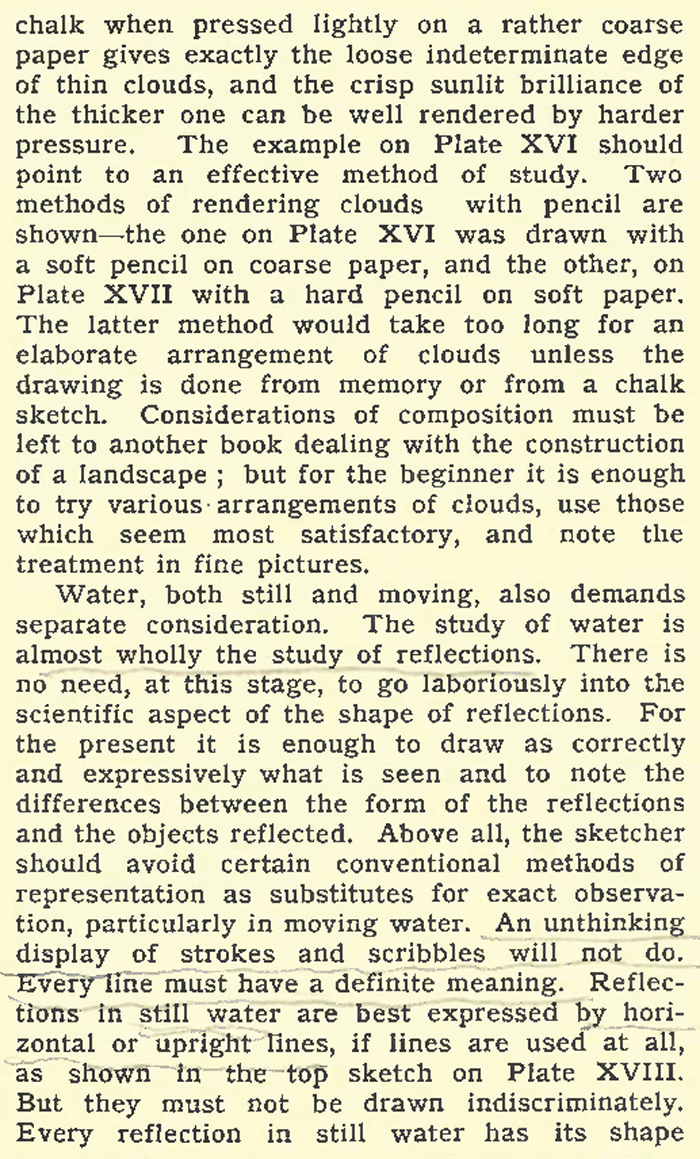

chalk when pressed lightly on a rather coarse paper gives exactly the loose indeterminate edge of thin clouds, and the crisp sunlit brilliance of the thicker one can be well rendered by harder pressure. The example on Plate XVI should point to an effective method of study. Two methods of rendering clouds with pencil are shown—the one on Plate XVI was drawn with a soft pencil on coarse paper, and the other, on Plate XVII with a hard pencil on soft paper. The latter method would take too long for an elaborate arrangement of clouds unless the drawing is done from memory or from a chalk sketch. Considerations of composition must be left to another book dealing with the construction of a landscape ; but for the beginner it is enough to try various arrangements of clouds, use those which seem most satisfactory, and note the treatment in fine pictures.

Water, both still and moving, also demands separate consideration. The study of water is almost wholly the study of reflections. There is no need, at this stage, to go laboriously into the scientific aspect of the shape of reflections. For the present it is enough to draw as correctly and expressively what is seen and to note the differences between the form of the reflections and the objects reflected. Above all, the sketcher should avoid certain conventional methods of representation as substitutes for exact observation, particularly in moving water. An unthinking display of strokes and scribbles will not do.

ieirline must have a definite meaning. Reflections in still water are best expressed by horizontal or upright Fines, if lines are used at all, as shown in the top sketch on Plate XVIII. But they must not be drawn indiscriminately. Every reflection in still water has its shape

and needs to be studied as carefully as the ObjeEt reflected.

Moving water cannot be represented ; it can only be suggested. Here it is the movement that has to be expressed. Generally the strokes should follow the form of the ripples as shown in the other two sketches.