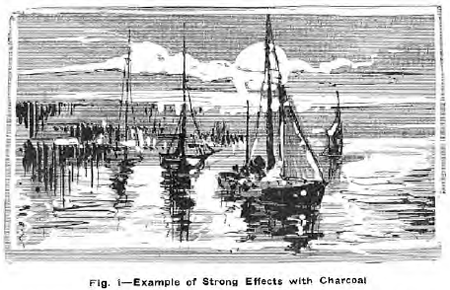

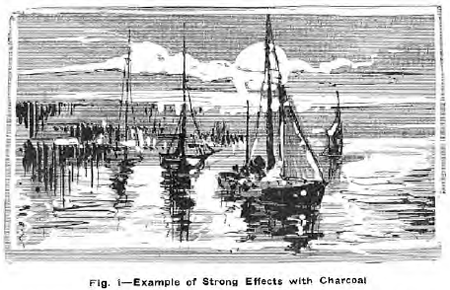

Charcoal is a material that can be used with striking effect and on a large scale. It is also adapted to the most careful work, where a high degree of finish is required. Charcoal is especially valuable as a medium, for the reason that it can be so easily erased. Charcoal is used in the principal art schools of the world for drawing from the cast and from the human figure. It is well adapted to sketching from nature. By its use, the most charming landscapes and marine effects may be obtained. For monochrome, moonlight effects, it is not to be surpassed.

Two Methods of Drawing in Charcoal Prevail.—First, that in which the charcoal point is used alone, the shading being put in with lines which are not blended, without the use of the stump or rubbing of any kind.

Second, that in which the charcoal is blended with the stump or a soft rag, no lines being visible in the modeling. This manner of drawing is most popular in schools, and with reason, for it is susceptible of higher finish than the first method described. It is by this means that charcoal and crayon portraits are drawn.

Paper for Charcoal and Crayon Drawing.—For general purposes, the rough charcoal paper, made especially for the purpose, is the best.

Crayon.—Black crayon comes in several numbers or degrees of hardness and is to be had in two forms. First, the wooden pencils, and also in the shape of short sticks. The latter should be fastened in a crayon holder while using. For most purposes, crayon No. 2 is sufficient.

In addition to this, a fine, black, powdered crayon, called "sauce crayon," may be used. It comes in handy when large masses of dark are necessary and is rubbed on with a stump.

Stumps are made of leather, chamois skin and paper. For school purposes, paper stumps will be all that need be used. The stumps come in two forms, one made in various sizes of rough paper, measuring from one-fourth to an inch or more in diameter.

The other form of paper stump is known as the tortillon, and is made of strips of paper rolled to a point, like spills. It is used in detail work, where the other form of stump would be too coarse.

Ordinary bread, at least a day old, that is free from butter, lard or milk in its making, is used for rubbing out charcoal or crayon, erasing mistakes, and taking out lights from a mass of dark. In order to correct a line or erase the charcoal by means of the bread, take a small piece between the fingers, roll it into a ball and shape it to a point, use it as you would a rubber eraser only more slowly.

A fine, soft, cotton rag is a necessary adjunct to work with charcoal or crayon. It is used sometimes to dust the charcoal from the paper, and if the charcoal has not been very heavily used, the rag is often sufficient to make an erasure without the use of bread or rubber. A rag is useful also when too much charcoal or crayon has been rubbed on a tone. If a shadow appears too black, a soft rag may be passed gently over the surface, when the superfluous charcoal or crayon will come off, leaving behind a tone more soft and light in quality. This tone can be worked over in any manner desired. The rag, too, may be used in sketching landscapes to spread a soft, flat mass, such as a sky. In many cases, it is preferable to use the stump for this purpose. In lieu of the "sauce," charcoal may be powdered and used in the same manner as the "sauce."

To "Fix" Drawings.—Unprotected, a charcoal drawing will become smeared and defaced. Hence it is necessary the drawing by the application of some varnish-like preparation. To use a brush for this purpose would be obviously wrong. A fixative may be made by using four ounces of alcohol, in which has been dissolved a few grains of white shellac. Fixative also comes ready prepared in bottles.

The fixative is applied to the surface of the drawing by spreading it by means of an atomizer. The atomizer used for medicinal and perfume spraying is not applicable to this purpose; the shellac in the fixative soon clogs the tubes. The cheapest, and as good as any, consists of two small tubes of tin. These are connected and fastened by a small hinge or pivot. One end is placed in the fixative and the other end taken in the mouth, and the breath blown through it. This causes the liquid to mount in the lower tube and dissolve in a cloud of spray so light as not to dislodge the delicate particles of charcoal, and yet attach them so firmly to the paper that ordinary rubbing will not efface the drawing.

In blowing through an atomizer, care should be taken to make the breath steady, avoiding short unequal puffs. The atomizer must be held sufficiently far from the paper to avoid causing the fixative to run down in streams, to the ruination of the drawing. If held too far from the drawing it will vaporize too much and fail to "fix" the charcoal.

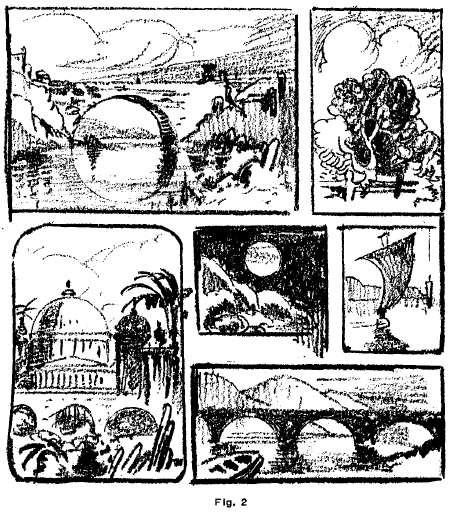

Simple exercises in charcoal. Fig. 2 is a group of sketches in which semi-circular shapes purposely prevail. By practicing curved lines, gracefulness of handling is acquired.

Charcoal.—In laying out a drawing, to be made by means of charcoal or crayon, make a faint outline of the shadows where they meet the light. After having done so, charcoal the mass of shadow within the outline, making a flat, even, dark tone. In order to do this with the charcoal, draw straight parallel lines, slightly oblique, almost touching each other, until the whole shadow is covered. A large paper stump, or the rag, is now used to unite these charcoal lines into one flat tone of dark. The stump is held in the fingers, so that about an inch of the point lies on the paper, not merely the tip end. With this, the charcoal is rubbed in until no lines appear, but instead an even tone of dark fills in the outline of the shadow.

Should too much charcoal get on the paper, while laying in a mass of shadow, it may be wiped off lightly and evenly with the rag. Then, if the tone has become too light, work on it again with the charcoal, as before, using the stump in the same way until it is satisfactory.

In this exercise, cover the entire surface of the paper with a single dark tone. Add the blacks and take out the high lights with white crayon or chalk. After all the shadows are put in and the proportions are found to be correct, further details may be added with the point of the charcoal or crayon. Keep a clean stump always at hand for delicate half tints. "Sauce" is sometimes used for putting in large masses of dark, such as shadows, drapery, etc. Sauce is a finely powdered crayon, but not used as such. The "sauce" should be rubbed off on a small piece of charcoal paper, and tacked on one side of the drawing for convenience. It is used for especially delicate tones. The charcoal or crayon point is always used in finishing up a drawing, with the darkest accents being put in last. The high lights are taken out with the bread rolled to a point, and should be made sharp and distinct.

Keep Paper Covered.—In rubbing on charcoal, and before using the stump, be sure to cover- the paper well, so that very little rubbing will spread the tone into an even mass. No matter how much charcoal is put on at first, the superfluity can be taken off with a rag. On the other hand, if there is not enough and one is tempted to rub the surface too hard, the paper becomes rotten and spoiled.

It is even more necessary than when using the pencil to avoid letting the hand rest directly on the paper ; have a sheet of clean writing paper to place underneath the hand.

In blocking-in, or when drawing long, sweeping lines, the hand should not be steadied upon the paper as in writing, but the pupil should try to acquire freedom of handling by practice, resting the hand upon the paper only when absolutely necessary, as in drawing fine details or when great precision is required.

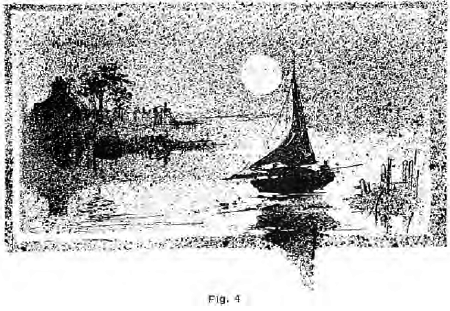

Charcoal Sketch.—Use tinted paper in making this sketch (Fig. 4), a gray tint being preferable. If tinted paper is unobtainable, use the stump or cloth according to previous directions, covering the entire surface of the paper as evenly as possible with a medium dark tint of the charcoal. Outline the details and put in the sky and sky reflections in the water. Next put in the heavy masses, such as the house at the left, and a boat with its reflection. Then the solid black and sharp details, such as the windows of the house, the spars of the boat, etc. If tinted paper is used, make the high lights, including the moon, by means of white chalk. If white paper is used, take out the high lights with a pointed rubber or bread.

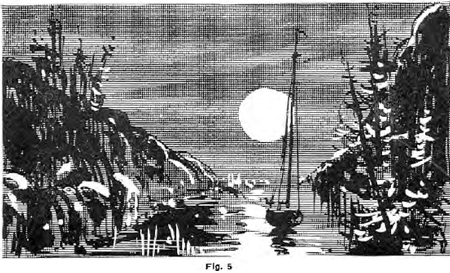

The moon is especially adapted as a leading motif in charcoal drawing, and for this reason so many moonlight scenes are introduced into the exercises in this chapter.

Pastel Painting

Pastel painting is akin to working with colored chalks or crayons. Pastels are soft enough to be powdered under the finger and graduated and blended by means of stumps. The latter is applied to cigar-shaped rolls of leather or paper, especially made for the purpose. Pastels lend themselves readily to the painter who desires to produce quick effect. They require no elaborate preparation and, unlike watercolor work, may he interrupted and resumed at will.

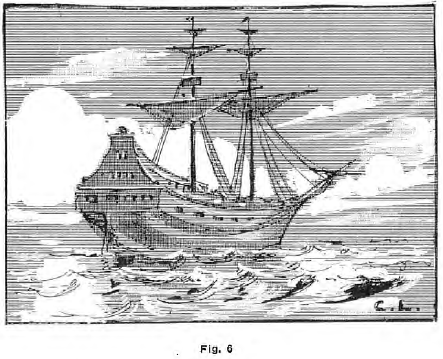

Pastels Produce Pretty Effects.-Applied to paper or cardboard, the pastel produces soft opaque shadows that have not the depth of oil painting, neither do they create the transparent effect of water-color painting. But the colors show freshly. Flesh tints may be produced with tenderness and brilliancy, while in landscape work, it appeals strongly to one desiring to produce sky effects, especially those of sunrise and sunset. Little skill is required in the blending of colors, but crisp detail and vigorous touches are generally found wanting in pastel painting. Very pretty effects may be had by cutting out stencils and instead of a brush using a soft cloth or piece of chamois, as described in the chapter devoted to Pastel-Stenciling. The pastels may then be rubbed on the cloth and by gently rubbing transferred to the paper. Different portions of the subject may be treated with various tints and the details afterward put in with a crayon. The examples in Figs. 6 and 7 were made by this means, although here shown in black and white. By making a single unit of ornament and repeating it, various designs, such as borders, etc., may be made.

While a drawing may sometimes be improved if the pencil or crayon lines are gently rubbed with the finger tip, rubber or. paper stump or soft rag, such devices should be avoided in early practice work. This method of softening is too temptingly easy and its use is apt to make the pupil careless in the matter of producing of soft effects with the point alone. "Stumping" must be done with considerable care or it will give the shading and outlines a dulled or rubbed appearance, not readily restcred by retouching.

In shading with pencil, crayon, etc., it is well to keep a piece of glazed or blotting paper under the hand to prevent rubbing. This will also prevent the paper from becoming warped through the warmth of the hand. Another precautionary measure against smudging, when shading, is to work downward from the upper part of the drawing. In a very important drawing the precaution may be taken to cover the entire drawing surface with a sheet of thin paper which may be torn away, piece by piece, as the finishing of the drawing progresses.

A FEW NEVER, NEVERS.

Never "rub off" a pen drawing until the ink is quite dry. If there are large wet spots of ink that simply won't. dry, dab them very slowly but gently with the corners of a blotting paper. Do not press the blotter flat as you would in blotting a letter. Do not try to get the ink quite dry with the blotter. Let the final moisure dry naturally so as to leave a smooth surface of ink.

Never make a very long tapering point to the lead pencil, unless there is some very fine detail to be worked up.

Never leave your ink bottle unstopped when not in use unless you want the ink to get thick, not to mention possibilities in the way of spilling.

Never dip your brush into the ink bottle, unless you are very careful not to touch the neck of the bottle with the brush. If the brush strikes the neck of the bottle while inserting it, the hairs will become separated and likely remain so. Of course there is no danger of doing so when withdrawing it from the bottle—in that case the brush can be wiped off on the inside of the neck of the bottle. The best plan is to pour out a few drops of ink on a saucer or ink slab. By so doing one can more easily regulate the supply of ink taken up by the brush.

Never leave less than a half inch margin of plain paper around your drawing, more will be better. Never try to see how many drawings you can get on one paper.

Never have two or more drawings facing different ways on a piece of paper. Do not draw on both sides of the paper. If you are suffering from a paper famine economize on the number of pictures. Keep down on the production but don't crowd.

Never use light greyish ink, or in fact any except very black ink.