As explained at the beginning of this treatise on pen and ink work, and also in the preface to this book, engravings to be run with type are made by two processes; viz., zinc etching and half tone. The halftone process will be explained, later, in connection with wash drawing. Zinc etching requires that everything to be engraved by that process should be in black on white, and practically anything that is black on white can be reproduced to a certain degree of fineness. For example, a page of this book, with the type on it, can be made into an engraving. And this page can just as readily be made the same size, or twice the size, or half the size, though, for various reasons, engravers prefer a reduction. From this, it will be readily seen that other things besides pen drawings may be reproduced by zinc etching—printed pages, illustrations, or, in fact, practically anything that is drawn in black on white paper. A drawing for this purpose could be made in lampblack, ivory black or crayon, and the last is often used, either by itself or in connection with pen lines.

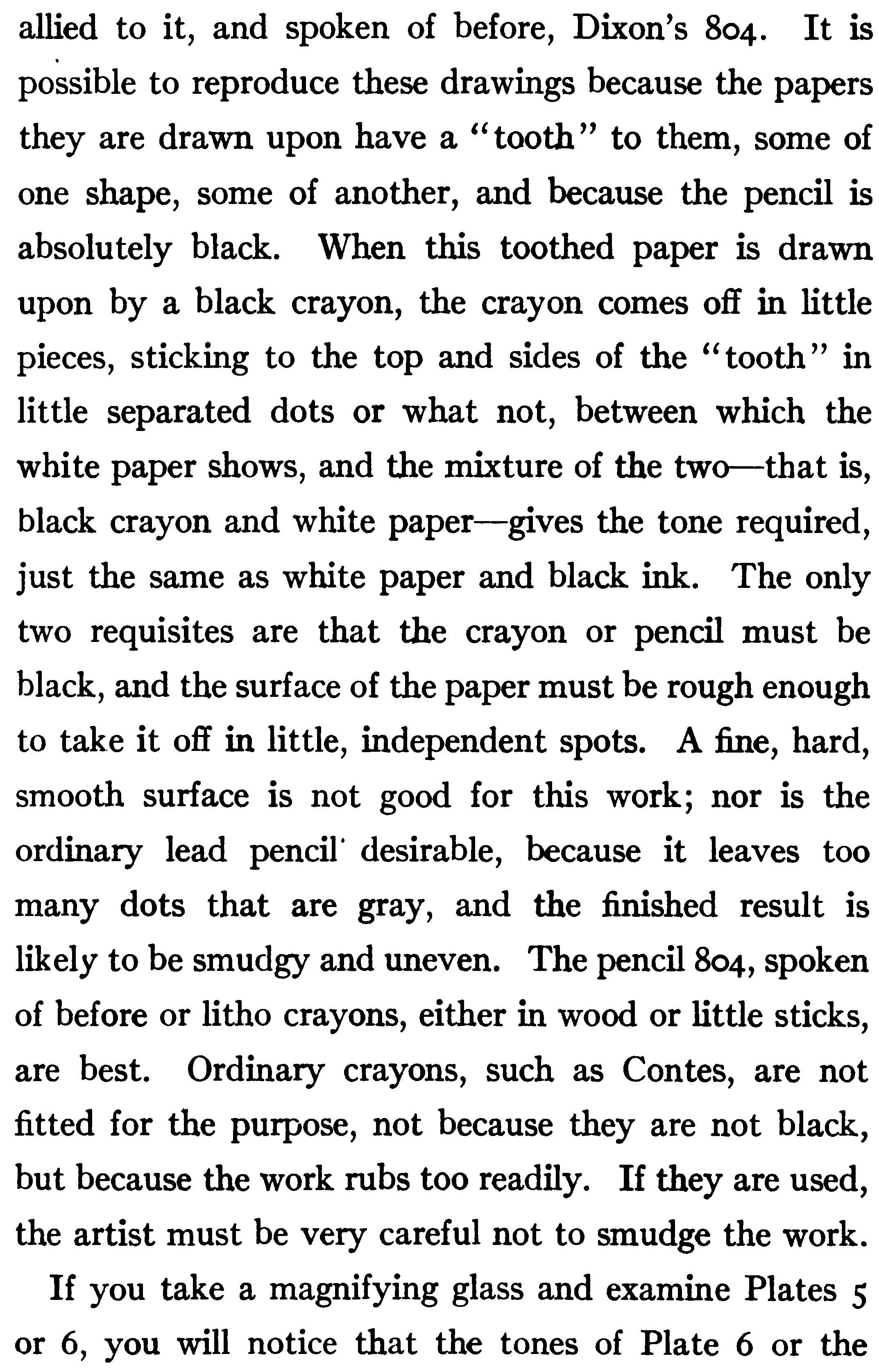

To turn back to the earlier plates of this book, Plates t, 2, and 3 are made with pen and ink, but Plates 4, 5, 6, and 7 are drawn with crayon, or with a pencil nearly allied to it, and spoken of before, Dixon's 804. It is possible to reproduce these drawings because the papers they are drawn upon have a "tooth" to them, some of one shape, some of another, and because the pencil is absolutely black. When this toothed paper is drawn upon by a black crayon, the crayon comes off in little pieces, sticking to the top and sides of the " tooth " in little separated dots or what not, between which the white paper shows, and the mixture of the two—that is, black crayon and white paper—gives the tone required, just the same as white paper and black ink. The only two requisites are that the crayon or pencil must be black, and the surface of the paper must be rough enough to take it off in little, independent spots. A fine, hard, smooth surface is not good for this work; nor is the ordinary lead pencil' desirable, because it leaves too many dots that are gray, and the finished result is likely to be smudgy and uneven. The pencil 804, spoken of before or litho crayons, either in wood or little sticks, are best. Ordinary crayons, such as Contes, are not fitted for the purpose, not because they are not black, but because the work rubs too readily. If they are used, the artist must be very careful not to smudge the work.

If you take a magnifying glass and examine Plates 5 or 6, you will notice that the tones of Plate 6 or the lines of Plate 5 are really masses of little, irregular dots between which the white paper shows. Plate 7 is drawn on different styles of paper, but the principle is the same. Each of these dots is black, and being black, photographs satisfactorily.

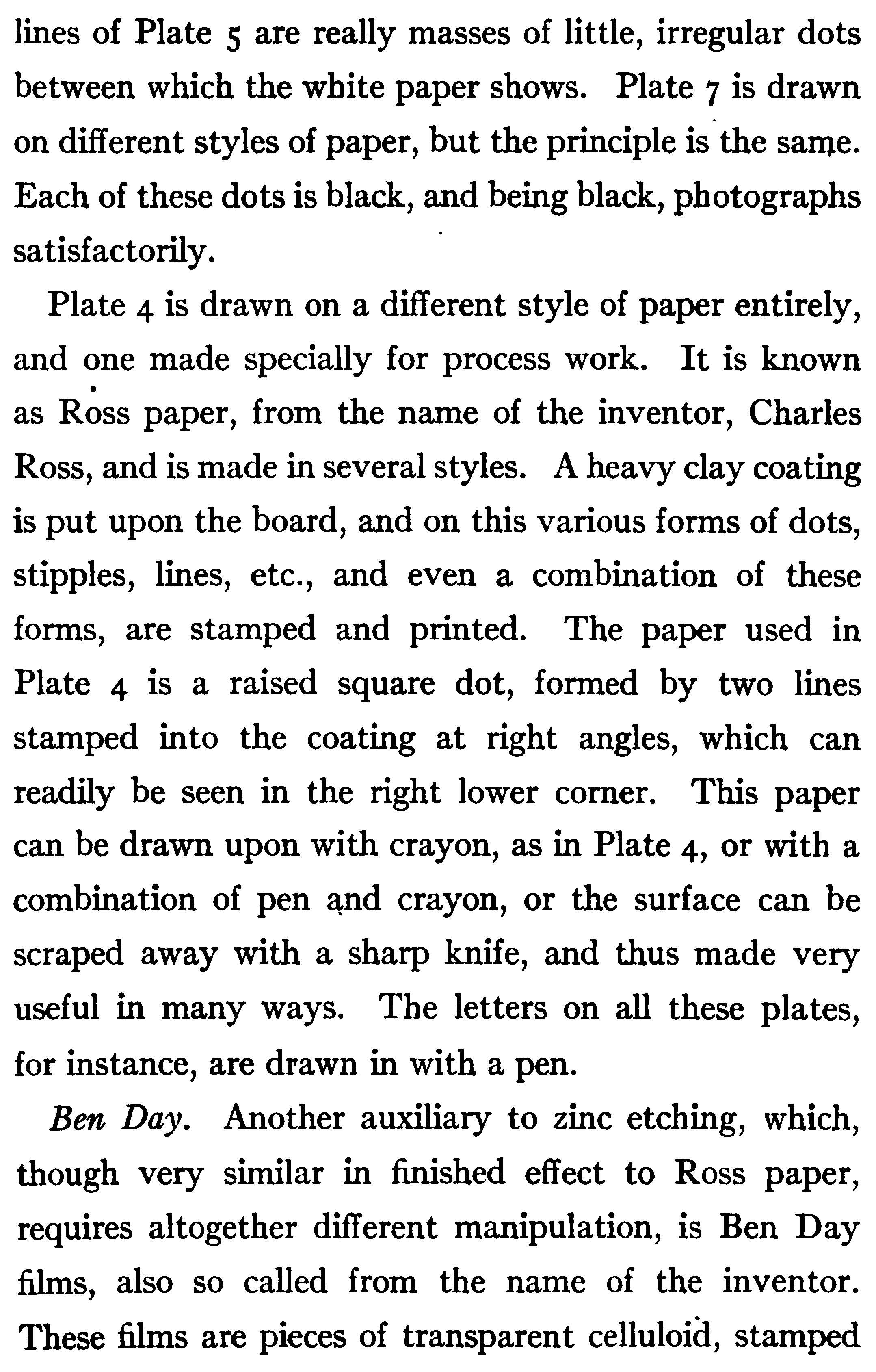

Plate 4 is drawn on a different style of paper entirely, and one made specially for process work. It is known as Ross paper, from the name of the inventor, Charles Ross, and is made in several styles. A heavy clay coating is put upon the board, and on this various forms of dots, stipples, lines, etc., and even a combination of these forms, are stamped and printed. The paper used in Plate 4 is a raised square dot, formed by two lines stamped into the coating at right angles, which can readily be seen in the right lower corner. This paper can be drawn upon with crayon, as in Plate 4, or with a combination of pen and crayon, or the surface can be scraped away with a sharp knife, and thus made very useful in many ways. The letters on all these plates, for instance, are drawn in with a pen.

Ben Day. Another auxiliary to zinc etching, which, though very similar in finished effect to Ross paper, requires altogether different manipulation, is Ben Day films, also so called from the name of the inventor. These films are pieces of transparent celluloid, stamped upon one side, in the same manner as Ross paper, but they are rolled up with ink so that the tops of the lines, dots, or stipples are covered with a thin coating of black ink. These films are then fixed in a frame, ink side down, and the- ink is transferred to the surface to be covered by rubbing the back with a stylus. The films, being transparent, can be seen through, and the tint placed upon any spot of the paper or zinc desired. At one time they were much used on paper, but at present are more often placed directly on the zinc plate. They are often used in lithography, as it is possible to do beautiful color work with them.

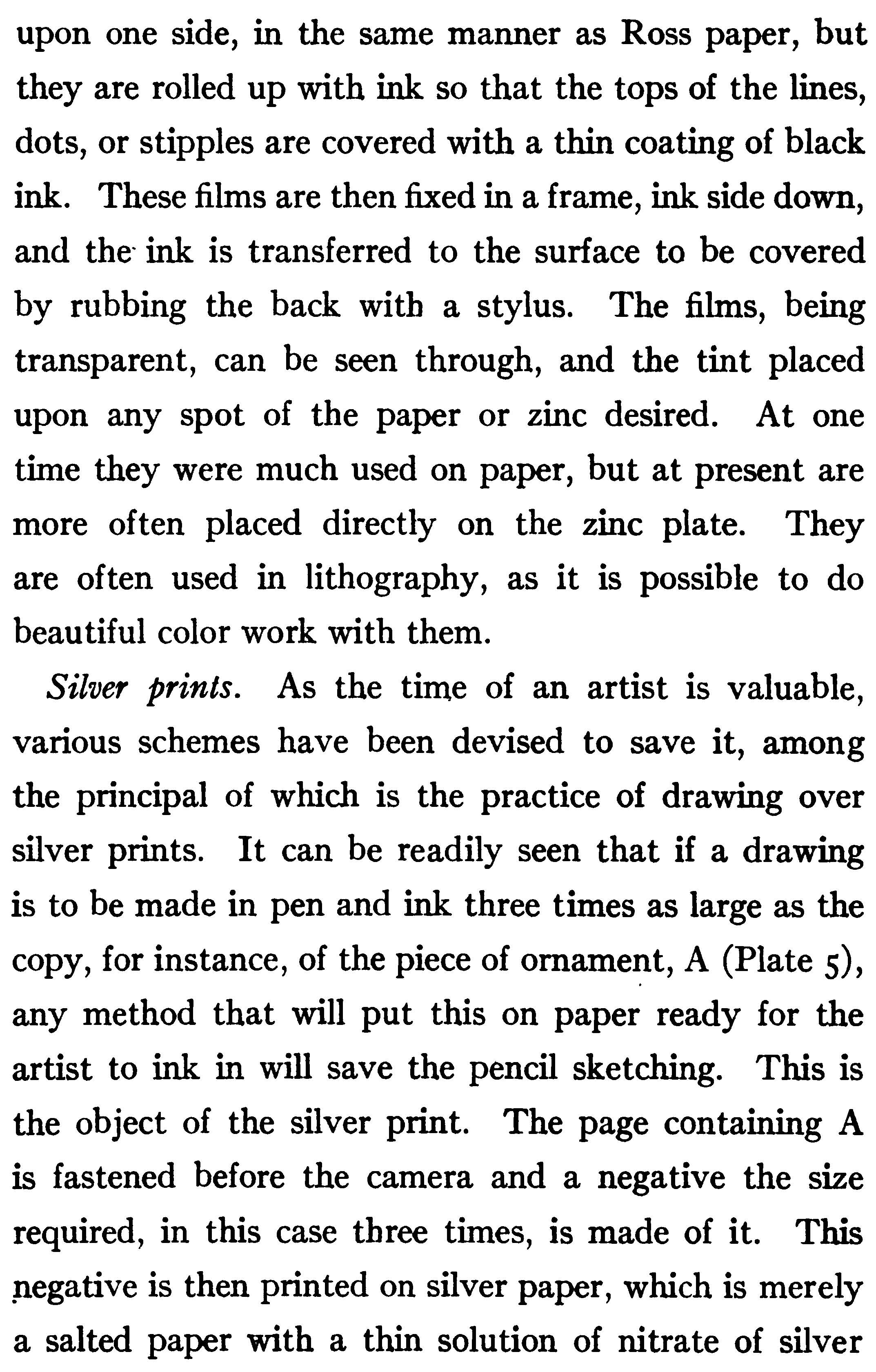

As the time of an artist is valuable, various schemes have been devised to save it, among the principal of which is the practice of drawing over silver prints. It can be readily seen that if a drawing is to be made in pen and ink three times as large as the copy, for instance, of the piece of ornament, A (Plate 5), any method that will put this on paper ready for the artist to ink in will save the pencil sketching. This is the object of the silver print.

The page containing A is fastened before the camera and a negative the size required, in this case three times, is made of it. This negative is then printed on silver paper, which is merely a salted paper with a thin solution of nitrate of silver on it, and printed. This print will be a copy of A, three times as large, in a light-brown tone, which answers the purpose of a pencil drawing to the artist, and which. will be exact in every detail. It is a comparatively easy matter for the artist to draw over this with pen and ink, as he has all the details of the drawing on the paper before him. When the pen drawing is finished the print is faded out with a solution of bichloride of mercury, leaving only the white paper with his pen drawing upon it. Waterproof drawing ink must, of course, always be used for this work, and all drawing with white must be left till the print is bleached and dried, or it will run and smear the drawing. If preferred, the outlines only of the pen drawing may be put in before bleaching, the details being filled in afterward. Many artists prefer to work in this way.

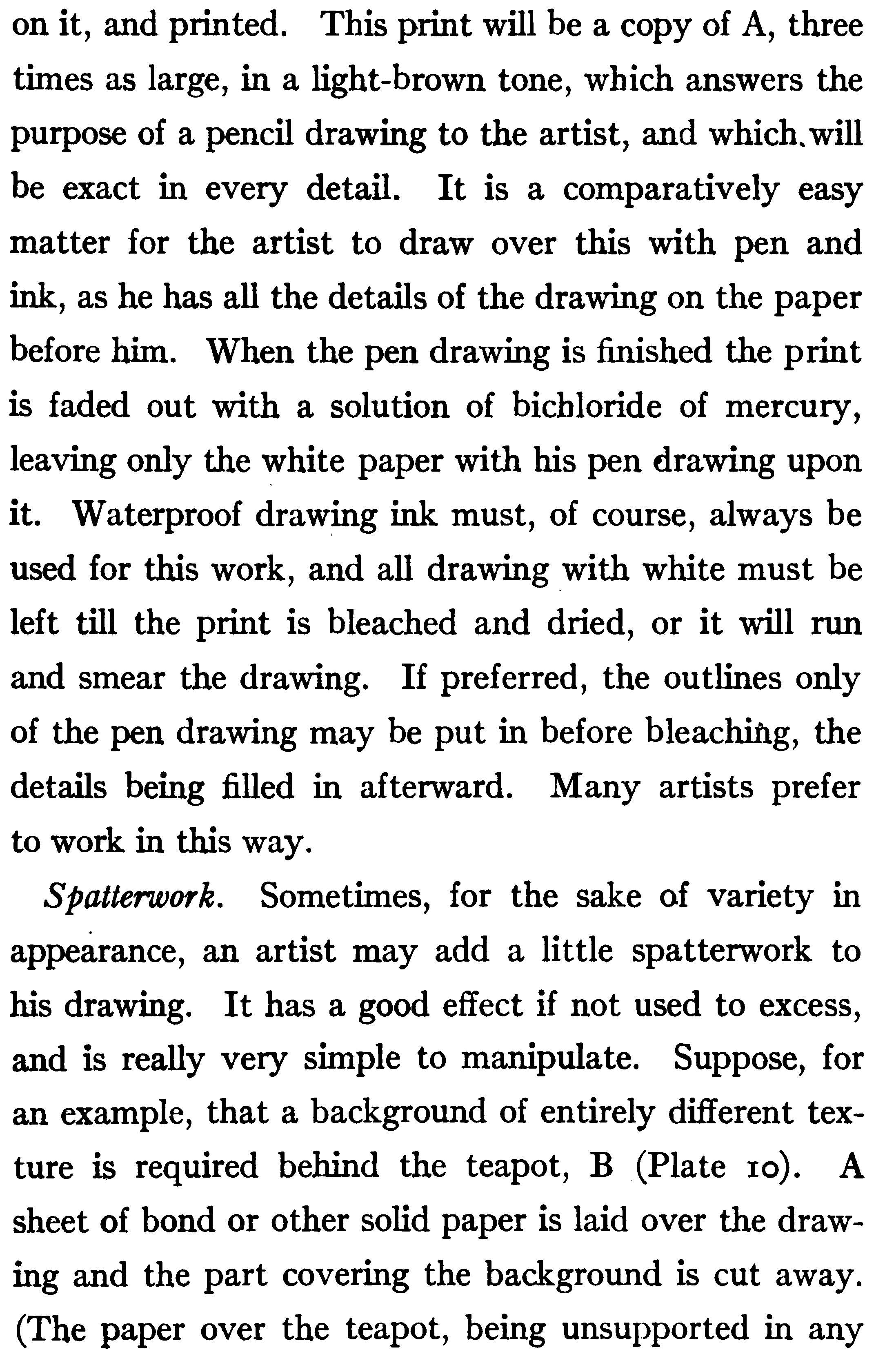

Sometimes, for the sake of variety in appearance, an artist may add a little spatterwork to his drawing. It has a good effect if not used to excess, and is really very simple to manipulate. Suppose, for an example, that a background of entirely different texture is required behind the teapot, B (Plate 1o). A sheet of bond or other solid paper is laid over the drawing and the part covering the background is cut away. (The paper over the teapot, being unsupported in any way, must be weighted down to keep it in place.) The bristles of an old toothbrush are cut down until they are fairly stiff, and a little ink put into a saucer and the brush dipped into it,, care being taken not to get too much ink on to the brush. A knife blade is then drawn over the ends of the bristles, and the hairs, in flying back, "spatter" the ink over the drawing. The parts to remain white are protected by the paper, which is called a "mask." Sometimes, instead of a mask, the drawing is painted with rubber cement, where it is desired to show untouched, and this is afterward removed with gasoline. For fine work, or work in which there are small places that must not be covered with the spatter, this is much the best way.

The camera—or rather the wet silver bath—has certain peculiarities in the way it reproduces certain colors. Red and yellow, for instance, photograph as practically black and blue as white, and advantage is sometimes taken of this to simplify the work of the artist. In Plates 4, 5, 6, and 7 we have samples of crayon or pencil drawing. These plates necessarily had to be sketched in, and, as it is, of course, impossible to go over them with a rubber after the finished drawings are made, for fear of spoiling the effect or smudging the work or erasing it altogether, the pencil

guide lines, if pencil was used, would have to be very light, so as not to photograph into the body of the work. In this event, they might be difficult to follow, or become lost in the mass of shading, and so be of little use. Advantage is taken of the fact that blue photographs white, and the sketching and laying out of these objects was done with a blue pencil, which was left upon the drawing. This is a common practice with artists, and a very useful one in drawings made for zinc etchings; and while the drawings themselves may look somewhat "mussy" to the amateur with their background of blue markings, yet they are very practical, and the method is a good one to use at times, particularly in pencil drawings that are to be reproduced, or on places where the use of a rubber is not advisable. Blue pencil does not work as well for wash, however, as for pen, as it is likely to move and become mixed with the color.