GETTING STARTED DRAWING MATERIALS

ASKETCH from nature may be drawn for several different purposes, and the par-

ticular purpose will largely determine the character of the sketch. The nature-lover may desire no more than a topographical note to remind him of an interesting experience. The student may require a more detailed study as part of his training. The artist may draw the scene as a subject for a picture, or as material for future use.

Generally speaking the purpose of a sketch is not a detailed study, but a seizing of the essentials of line, tone, and construction—an addition to the stock of knowledge and a means of recalling impressions at a later date.

Few artists are able to invest their finished pictures with the freshness of the sketch. The comparatively unimportant facts obtrude and tend to hide the full significance of the fundamentals. The details of leaves and stems, roofs and stones, doors and windows, draw the attention from the sweeping lines, broad masses, and the underlying evidences of life and movement.

To all but the artist of vision and experience, the slight sketch is, more often than not, a delusion

and a snare. It suggests much, but it tells little. Unless the artist can fill in the gaps by knowledge, memory, or by other sketches, the vague note, however facile, tempts him to commence a picture which he cannot finish.

There is a common opinion that a quick sketch demands less skill and training than a completed drawing. The truth lies in the opposite direction. For the sketch is an expression, in comparatively few strokes, of many facts to be read between the lines. These remarks should not discourage the beginner, but rather stimulate him to study in such a way that his sketches may become the means of valuable service.

MATERIALS

MANY sketchers, professional as well as amateur, go through life unconscious of many of the materials they might enjoy :

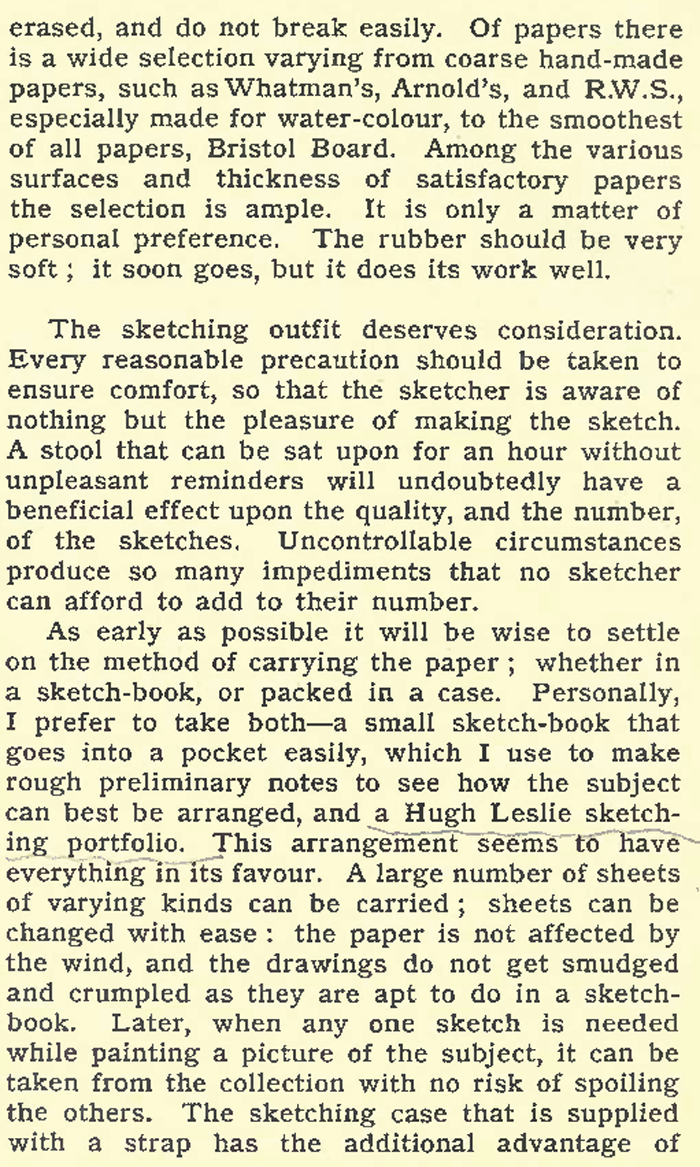

unaware of the sense of ease which comes of just the right pencil and paper to suit their personal tastes. There is a comfortable feeling of agreement between some papers and pencils—a condition which is communicated to the sketcher and the sketch. Too much emphasis can hardly be laid, right at the beginning, upon the necessity for those materials which help the sketcher to make his best sketch. As there is no best for all, every one must experiment for himself. Does he prefer a hard, medium, or soft pencil, a smooth, medium, or rough paper ? If he wants to produce a hazy, suggestive, atmospheric drawing he may prefer a soft pencil and rough paper. If he is more mindful of definition he will select a smooth paper and probably a medium pencil. If he desires to combine definition with both delicacy and strength a si. j.-1.2911_21 aper and three or four pencils of varying strength should meet ins' case.—ri-rt no one prefeii-7. gritty pencil with a point that breaks at the inspired moment, when a little extra pressure is applied, or a paper that does not ' take ' the pencil readily.

Winsor & Newton's 'Winton ' drawing pencils combine the three essential qualities of a good pencil ; they have a silky texture, are easily

erased, and do not break easily. Of papers there is a wide selection varying from coarse hand-made papers, such as Whatman's, Arnold's, and RW.S., especially made for water-colour, to the smoothest of all papers, Bristol Board. Among the various surfaces and thickness of satisfactory papers the selection is ample. It is only a matter of personal preference. The rubber should be very soft ; it soon goes, but it does its work well.

The sketching outfit deserves consideration. Every reasonable precaution should be taken to ensure comfort, so that the sketcher is aware of nothing but the pleasure of making the sketch. A stool that can be sat upon for an hour without unpleasant reminders will undoubtedly have a beneficial effect upon the quality, and the number, of the sketches. Uncontrollable circumstances produce so many impediments that no sketcher can afford to add to their number.

As early as possible it will be wise to settle on the method of carrying the paper ; whether in a sketch-book, or packed in a case. Personally, I prefer to take both—a small sketch-book that goes into a pocket easily, which I use to make rough preliminary notes to see how the subject can best be arranged, and a Hugh Leslie sketching portfolio. This arrangeniErif-"Febsm

everything favour. A large number of sheets

of varying kinds can be carried ; sheets can be changed with ease : the paper is not affected by the wind, and the drawings do not get smudged and crumpled as they are apt to do in a sketchbook. Later, when any one sketch is needed while painting a picture of the subject, it can be taken from the collection with no risk of spoiling the others. The sketching case that is supplied with a strap has the additional advantage of

2 13 or Med 1 tkin. 5uifie e

68 Cli C 0 rse Sirfa

0

Mar

()-

6 H 211 rie)

5ixceree3 ori.2.)ri.sroi • oard

Plate I

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

leaving both hands free at any moment to sharpen a pencil. A quarter imperial size is large enough for most occasions, but when a good deal of detail has to be done, such as in some architectural drawings, a half imperial size may be called for. The information given at the end of this book contains all that can reasonably be desired.

HOW TO BEGIN

TEMPERAMENTS vary. Some want to start with great views that make the most experienced hesitate. Others want to prac-

tise beforehand at home to get used to the materials. Some fear to venture before they have copied other people's sketches in order to get a technique. It goes without saying that it is of little use for any one but a rare genius to commence sketching from nature until he has acquired a little technical skill, and some habits of correct observation, with resultant knowledge, of the differences between the real shapes of simple things and their appearances. Whoever cannot draw a flower-pot indoors cannot expect to draw a chimney-pot out of doors. All the problems involved in the drawing of a box or a brick had better be solved before attempting a house or a street. But as soon as the necessary preliminary training has been gone through it is better to go straight to nature without hesitation or forebodings. If you must begin at the difficult end, do so, but retire when convinced of your mistake. Most people err on the side of timidity, which is far worse.

A little preliminary practice in handling and in experimenting with various pencils and papers should certainly be done before attempting to sketch. It would be an absurd waste of time and effort to achieve a technical method by

Plate II

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Plate III

aimless blundering or to trust to luck to hit upon suitable methods and materials by accident. Find out first what the medium can do, and then learn to do it efficiently and expressively as you sketch.

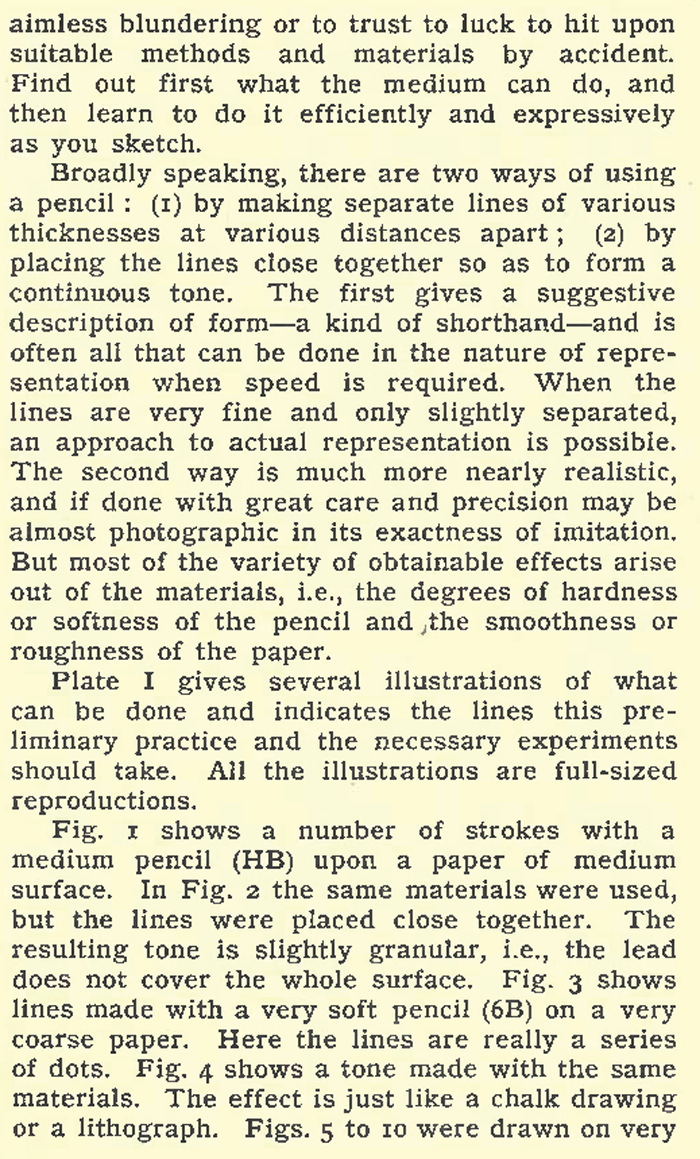

Broadly speaking, there are two ways of using a pencil : (1) by making separate lines of various thicknesses at various distances apart ; (2) by placing the lines close together so as to form a continuous tone. The first gives a suggestive description of form—a kind of shorthand—and is often all that can be done in the nature of representation when speed is required. When the lines are very fine and only slightly separated, an approach to actual representation is possible. The second way is much more nearly realistic, and if done with great care and precision may be almost photographic in its exactness of imitation. But most of the variety of obtainable effects arise out of the materials, i.e., the degrees of hardness or softness of the pencil and the smoothness or roughness of the paper.

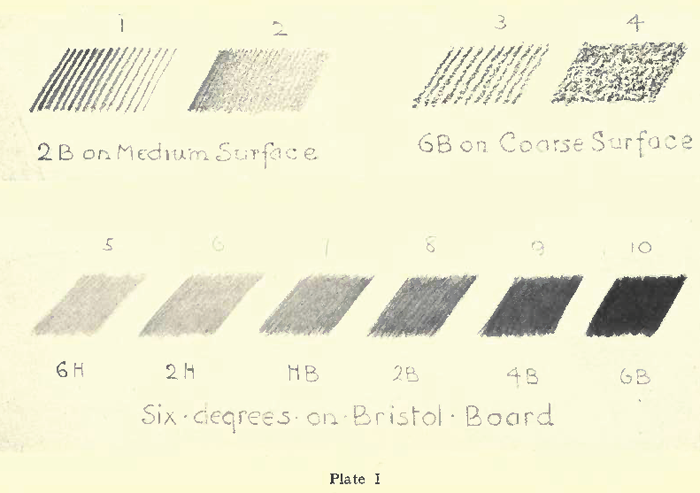

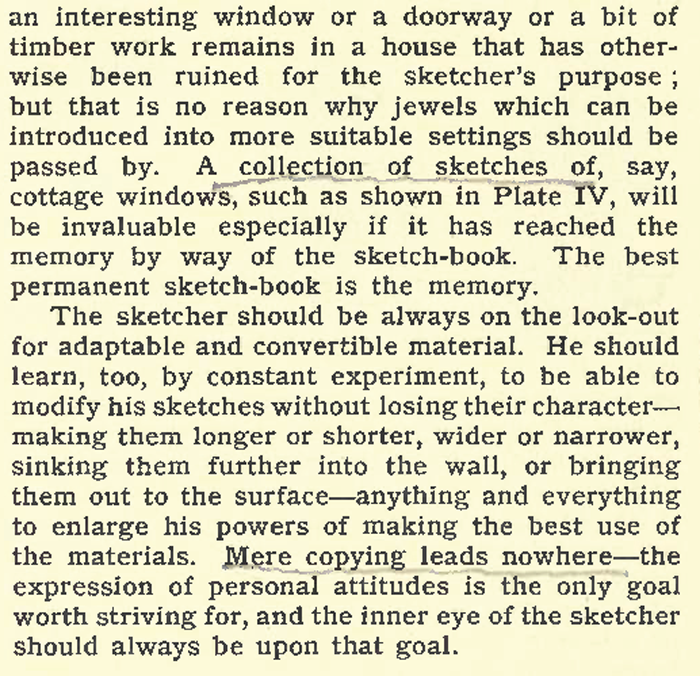

Plate I gives several illustrations of what can be done and indicates the lines this preliminary practice and the necessary experiments should take. All the illustrations are full-sized reproductions.

Fig. i shows a number of strokes with a medium pencil (HB) upon a paper of medium surface. In Fig. 2 the same materials were used, but the lines were placed close together. The resulting tone is slightly granular, i.e., the lead does not cover the whole surface. Fig. 3 shows lines made with a very soft pencil (6B) on a very coarse paper. Here the lines are really a series of dots. Fig. 4 shows a tone made with the same materials. The effect is just like a chalk drawing or a lithograph. Figs. 5 to io were drawn on very

smooth paper (Bristol board) with 6H, 2H, HB, 2B, 4B, and 6B pencils respectively. In each case the result is as smooth as a wash : there is no visible granulation.

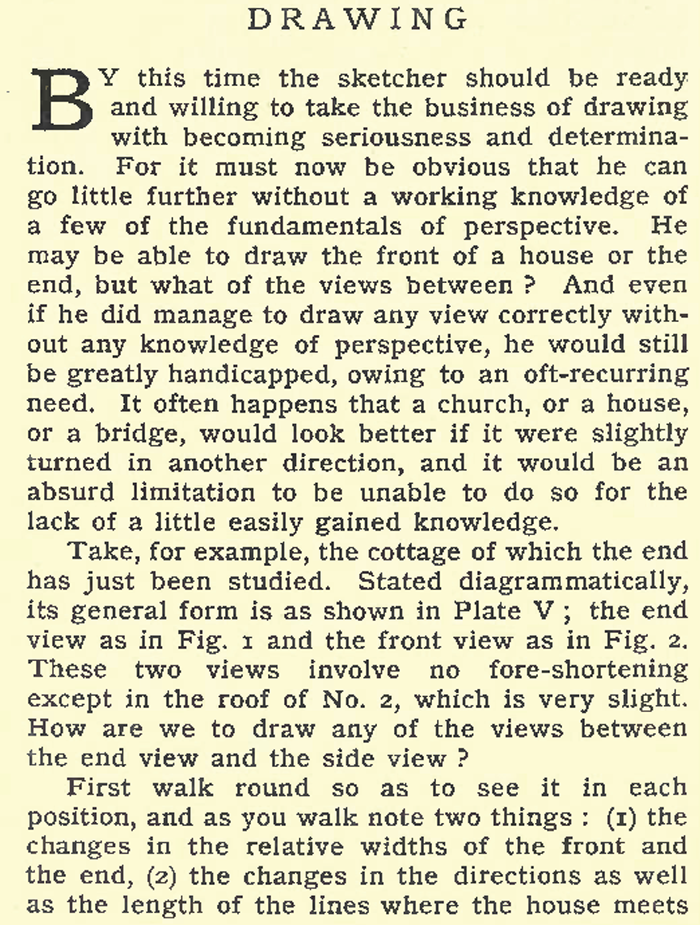

Plate II illustrates two of the ways just described. Figs i and 2 were drawn with a hard pencil (F) on a rather smooth paper, with clear separated lines as in a pen drawing. Figs. 3 and 4 were drawn on the same paper with a soft pencil (3B) on the same paper. The second pair give a somewhat realistic effect with a pleasant granular surface, while the first pair are only summarized descriptions.

The four drawings of the trunk of a tree on Plate II were drawn with a very soft pencil (4B) on the coarsest Whatman's paper, and illustrates an admirable method for expressing bold effects and rugged surfaces. Plate XV, among several others, was drawn on smooth paper with four pencils of widely differing degrees. By this method, strength, refinement, and exact delineation can be carried to the greatest extent of which the medium is capable.

A few hours spent in trying these methods (not continuously, but occupying a few minutes at a time) will be of great help in deciding upon a technique. But the method or methods to be adopted finally should come after a good deal of actual sketching on the spot. From long experience I recommend every one to make several drawings in several styles as soon as possible after returning from sketching. Try two or three surfaces of paper and several degrees of pencils. Away from disturbing minor details, while the general impression is still strong, it is often easier to decide upon the most suitable treatment, and, what is more important, such experiments give confidence to future efforts.

Plate IV

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

2.

3

4

Plate V

I shall assume that most readers prefer to begin with simple bits ' that call for less skill than perseverance. Nearly every one seems to want to commence operations in a quiet country village with quaint cottages, a church, a bridge, some farm buildings, and other charming characteristics of English rural life. For that reason, I propose, first, to take an imaginary village containing all that is necessary to show how to sketch what one is likely to find in such a place, study the details in progressive order of difficulty and afterwards to arrange them to suit pictorial purposes. These sketches will be made in various ways, partly because the method suits the subject, but principally to help the reader, by demonstration, to select methods for himself.

Plate II consists of four drawings of two simple subjects, which, for several reasons, will serve as an excellent start for the beginner, and at the same time is worthy of the attention of the experienced. A collection of sketches of such subjects make very valuable material for use ( later on. Introduced into a dull part of an otherwise unsatisfactory picture it may give just that touch of interest and variety needed. Features of this kind should be sketched from several points of view. Whenever another bit of railings IS— found, note its similarities to, and differences from, those already studied, draw them from memory, and try to construct others. The railings in Plate II were not copied from nature ; they were added to and reconstructed from knowledge gained by many sketches.

Just now, however, the main reason for selecting such a subject is that it can be made a means of gaining confidence and freedom of handling unimpeded by difficulties in drawing. It matters little if the shape is not correctly

copied providing the drawing serves its principal purpose.

From the beginning, however, regard this and every drawing as something to be used in a picture. Try to fit little bits of landscape or some other harmonious features round it as shown in Plate II ; however clumsily it is done at first it is necessary practice. Try it several times, at every opportunity, and whenever an idea occurs. In short, draw constructively, imaginatively, and expressively from the first sketch.

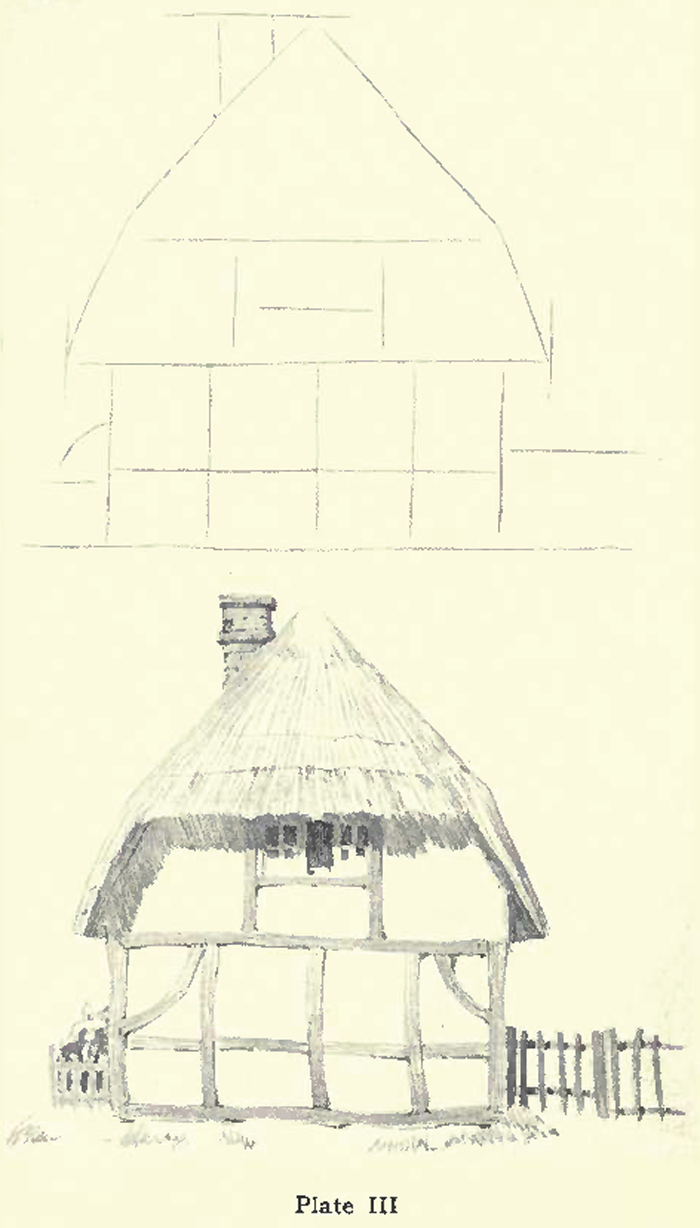

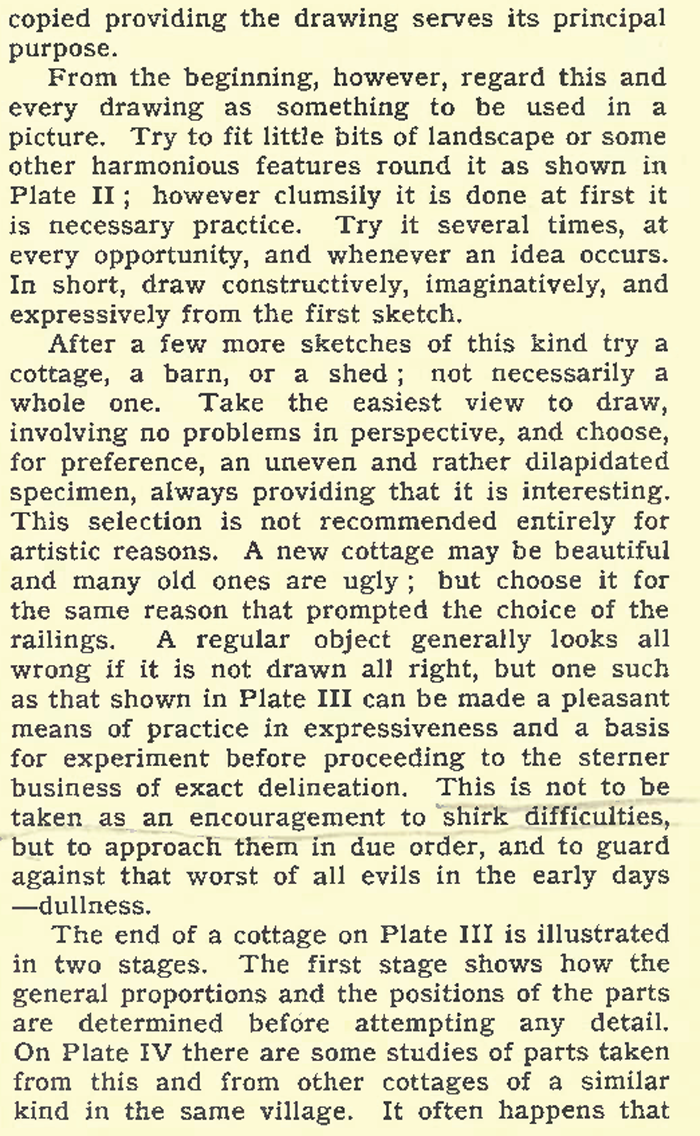

After a few more sketches of this kind try a cottage, a barn, or a shed ; not necessarily a whole one. Take the easiest view to draw, involving no problems in perspective, and choose, for preference, an uneven and rather dilapidated specimen, always providing that it is interesting. This selection is not recommended entirely for artistic reasons. A new cottage may be beautiful and many old ones are ugly ; but choose it for the same reason that prompted the choice of the railings. A regular object generally looks all wrong if it is not drawn all right, but one such as that shown in Plate III can be made a pleasant means of practice in expressiveness and a basis for experiment before proceeding to the sterner business of exact delineation. This is not to be taken as an encouragement to shirk difficulties, but to approach them in due order, and to guard against that worst of all evils in the early days —dullness.

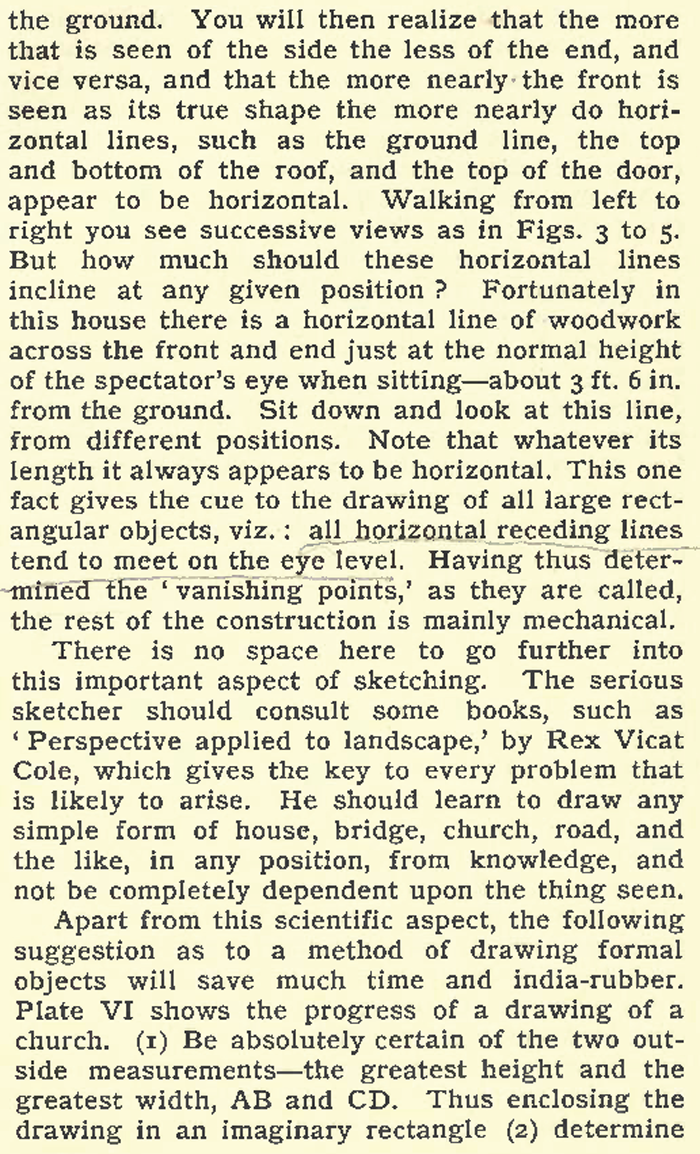

The end of a cottage on Plate III is illustrated in two stages. The first stage shows how the general proportions and the positions of the parts are determined before attempting any detail. On Plate IV there are some studies of parts taken from this and from other cottages of a similar kind in the same village. It often happens that

1

2

3

Plate V [

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Jjt r

C42 ^

41 44).

I 1

it - r!- (1•1

..- ,t.

Al

-., • rl for i 1 . ,

Plate VII

an interesting window or a doorway or a bit of timber work remains in a house that has otherwise been ruined for the sketcher's purpose ; but that is no reason why jewels which can be introduced into more suitable settings should be passed by. A collrstion of sketches of, say, cottage windows, such as shown in Plate IV, will be invaluable especially if it has reached the memory by way of the sketch-book. The best permanent sketch-book is the memory.

The sketcher should be always on the look-out for adaptable and convertible material. He should learn, too, by constant experiment, to be able to modify his sketches without losing their character—making them longer or shorter, wider or narrower, sinking them further into the wall, or bringing them out to the surface—anything and everything to enlarge his powers of making the best use of the materials. Mere copying leads nowhere—the expression of personal attitudes is the only goal worth striving for, and the inner eye of the sketcher should always be upon that goal.

DRAWING

BY this time the sketcher should be ready and willing to take the business of drawing with becoming seriousness and determina-

tion. For it must now be obvious that he can go little further without a working knowledge of a few of the fundamentals of perspective. He may be able to draw the front of a house or the end, but what of the views between ? And even if he did manage to draw any view correctly without any knowledge of perspective, he would still be greatly handicapped, owing to an oft-recurring need. It often happens that a church, or a house, or a bridge, would look better if it were slightly turned in another direction, and it would be an absurd limitation to be unable to do so for the lack of a little easily gained knowledge.

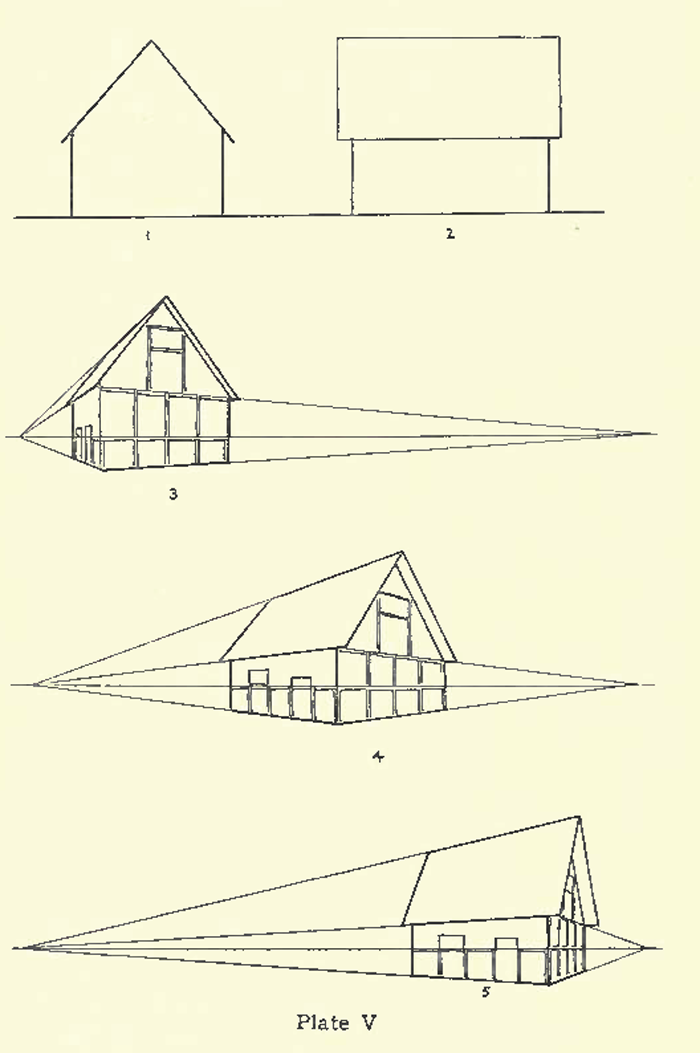

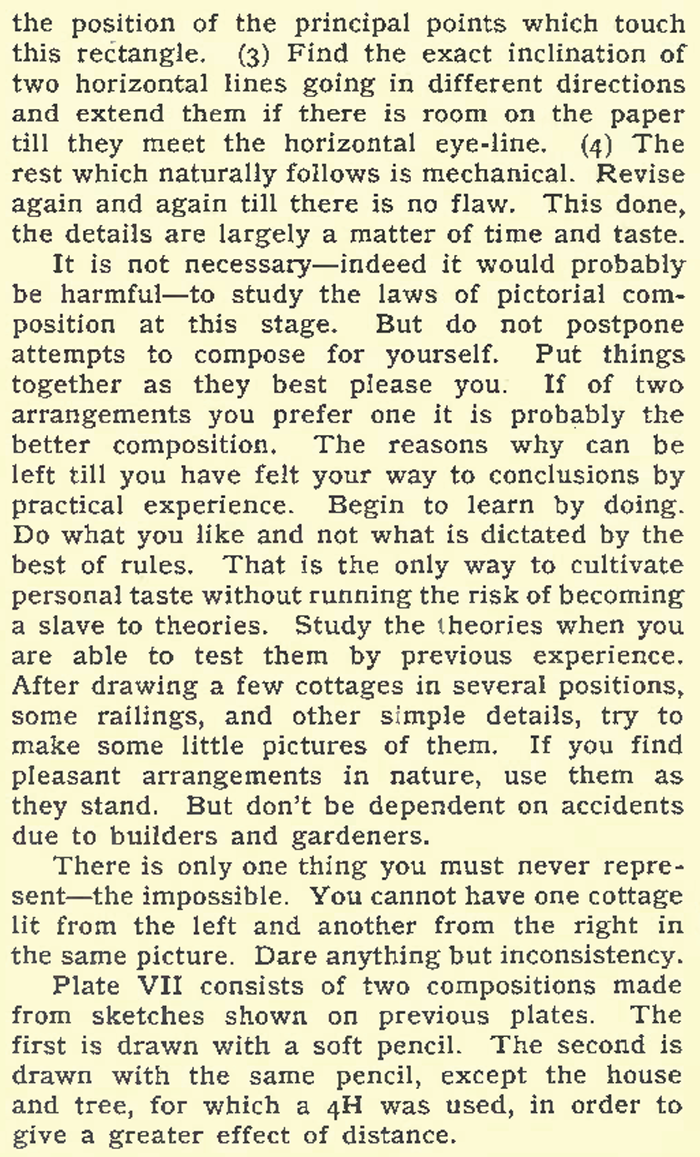

Take, for example, the cottage of which the end has just been studied. Stated diagrammatically, its general form is as shown in Plate V ; the end view as in Fig. z and the front view as in Fig. 2. These two views involve no fore-shortening except in the roof of No. 2, which is very slight. How are we to draw any of the views between the end view and the side view ?

First walk round so as to see it in each position, and as you walk note two things : (/) the changes in the relative widths of the front and the end, (2) the changes in the directions as well as the length of the lines where the house meets

Plate VIII

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Plate IX

the ground. You will then realize that the more that is seen of the side the less of the end, and vice versa, and that the more nearly the front is seen as its true shape the more nearly do horizontal lines, such as the ground line, the top and bottom of the roof, and the top of the door, appear to be horizontal. Walking from left to right you see successive views as in Figs. 3 to 5. But how much should these horizontal lines incline at any given position ? Fortunately in this house there is a horizontal line of woodwork across the front and end just at the normal height of the spectator's eye when sitting—about 3 ft. 6 in. from the ground. Sit down and look at this line, from different positions. Note that whatever its length it always appears to be horizontal. This one fact gives the cue to the drawing of all large rectangular objects, viz. : all horizontal receding lines tend to meet on the eye level. Having thus deter--mined the ' vanishing points,' as they are called, the rest of the construction is mainly mechanical.

There is no space here to go further into this important aspect of sketching. The serious sketcher should consult some books, such as ' Perspective applied to landscape,' by Rex Vicat Cole, which gives the key to every problem that is likely to arise. He should learn to draw any simple form of house, bridge, church, road, and the like, in any position, from knowledge, and not be completely dependent upon the thing seen.

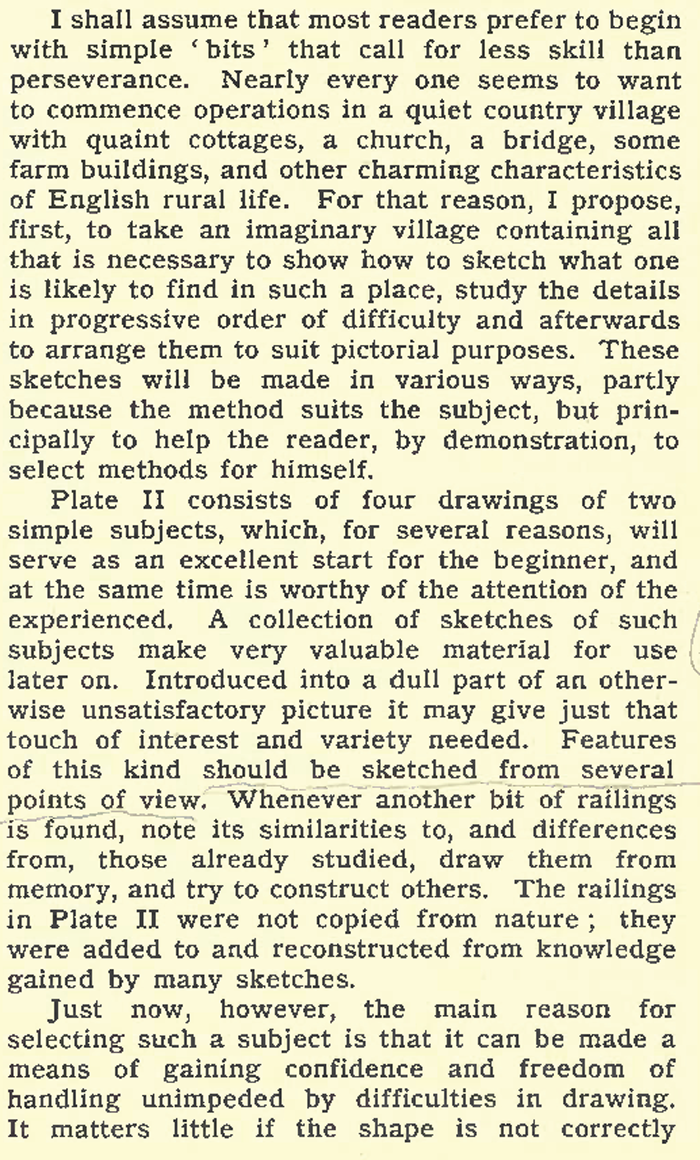

Apart from this scientific aspect, the following suggestion as to a method of drawing formal objects will save much time and india-rubber. Plate VI shows the progress of a drawing of a church. (r) Be absolutely certain of the two outside measurements—the greatest height and the greatest width, AB and CD. Thus enclosing the drawing in an imaginary rectangle (2) determine

the position of the principal points which touch this rectangle. (3) Find the exact inclination of two horizontal lines going in different directions and extend them if there is room on the paper till they meet the horizontal eye-line. (4) The rest which naturally follows is mechanical. Revise again and again till there is no flaw. This done, the details are largely a matter of time and taste.

It is not necessary—indeed it would probably be harmful—to study the laws of pictorial composition at this stage. But do not postpone attempts to compose for yourself. Put things together as they best please you. If of two arrangements you prefer one it is probably the better composition. The reasons why can be left till you have felt your way to conclusions by practical experience. Begin to learn by doing. Do what you like and not what is dictated by the best of rules. That is the only way to cultivate personal taste without running the risk of becoming a slave to theories. Study the theories when you are able to test them by previous experience. After drawing a few cottages in several positions, some railings, and other sample details, try to make some little pictures of them. If you find pleasant arrangements in nature, use them as they stand. But don't be dependent on accidents due to builders and gardeners.

There is only one thing you must never represent—the impossible. You cannot have one cottage lit from the left and another from the right in the same picture. Dare anything but inconsistency.

Plate VII consists of two compositions made from sketches shown on previous plates. The first is drawn with a soft pencil. The second is drawn with the same pencil, except the house and tree, for which a 4H was used, in order to give a greater effect of distance.