Home > Directory of Drawing Lessons > How to Improve Your Drawings > Drawing Lights and Shadows > > Lights and Shadows Art Lessons

How to Draw Lights and Shadows on Curved and Flat Objects as Well as Reflected Lights and Cast Shadows

|

|

Light and ShadeHow and Where to Place light and shade in a drawing is an oft recurring source of perplexity to the beginner. It is the more perplexing because often all light and shade in a one-color picture are merely substitutes for color as seen in nature. Light and shade values in a black and white drawing are merely relative in their attempt to imitate the pigments by which nature lets us discern form. In drawing, forms are represented by outlines, or by light and shade areas, or by a combination of both. If light were to pervade a room evenly—the light not coming from any particular direction, as from the sun, or some fixed artificial light or lights—there would be no shadows.

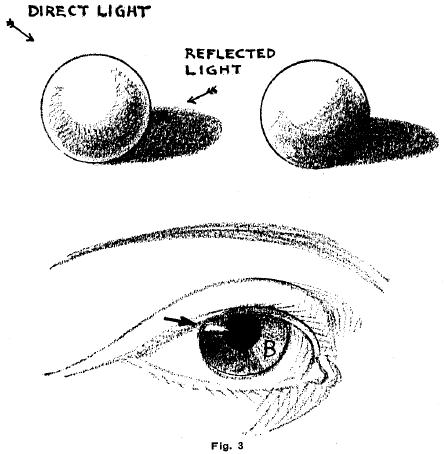

We could then perceive such forms only as they were made visible by their different colors. Every Curved Object Has Two Lights.An even opaque object, if it is curved, has its brightest and its darkest side, and intermediate parts where light and shade seem to combine. The main part of brightness in an object is called the high light. The darkest part of an object is not necessarily the part most distant from the chief point of light, for the reflected lights play a part in lighting up just those portions that seem in most need of the borrowed lights—"borrowed lights" being the term frequently applied to certain forms of reflected light. (See Fig. 3.) Reflected Lights Enable Us to Distinguish Forms.The point of light indicated by the arrow at left of iris of the eye is a sharp, reflected light. The lighter portion of the iris at B is caused by diffused light—the effect of the light passing through the semi-transparent eyeball. The portion of the eyeball nearest the light is always darker than the other side. except that portion where the point of reflected light appears as shown by the arrow. Cast Shadows Darkest.The shadow cast by an object is usually darker than the object itself, because the part receiving the shadow is not apt to be the recipient of the reflected lights. The shadow follows the shape of an object to the extent that the surface, by its angles and variation of form and shape, will permit it. (See Fig. 5.) In order to draw shadows with absolute correctness, certain rules should be followed that are to be obtained only by a study of the most advanced rules in perspective. To attempt here to explain these rules would take more space than is allotted to the subject, and, besides, could not be made plain or interesting to teacher or pupil. The Course of Shadows.Shadows follow or are broken by the shapes of the objects on which they are cast. Note that the shadows in Fig. 4 are thrown in (diffused) straight lines on the wall, while in Fig. 5 the shadow of the stick is broken by the steps on which the shadow is cast.

Shadows from the Point of Projection.—Shadows broaden if there are reflected lights that may cause multiplication of the shadows ; thus, in Fig. 4 the shadows broaden as they leave the spouts. This is owing to the presence of reflected light. Reflected lights are those which are thrown from one object to another, each object in turn reflecting light which, coming in contact with still another object, causes the latter to throw a shadow. It will be enough to lay down a few condensed rules for ordinary use in the study of light and shade. Intercepted rays of light cause shadows. (See Figs. and 2.) The light may be direct from the sun, candle, lamp or any glowing substance. These throw strongly defined shadows. (See Figs. i and 2.) Or the light may be caused by diffused or reflected rays. Diffused lights are such as are given by a north window without the presence of sunshine, by the lights we receive on a cloudy or misty day. These lights cast soft and more or less undefined shadows. Reflected Light.A reflected light is cast into a room by an outside wall opposite a window, and is usually a subdued light. The reflected light cast by a mirror should not strictly be considered as a reflected light, for the rays are almost as strong as the source itself. The side of a cloud in the east will, at sunset, cast a reflected light on the earth. In the same manner will the side of a piece of chalk facing the window cast a reflected light on an object facing opposite the window light, but so placed as to be within the rays of the bit of chalk. The general effect is the same, be the scale great or small. Shadows Have no Substance.An object seen through a shadow, but beyond its area, is seen as plainly as if the shadow were not there. A shadow is not a dark object in itself. If an object comes within the scope of a shadow thrown by another object it will receive that shadow, but if it is beyond the shadow, although within the direct line cast by the shadow it will not be affected. Shadows are invisible unless they have some plane or object upon which to fall. In landscape work one is apt to forget the direction from which the light comes. (See Figs. 10, 11 and 12.) Density of Atmosphere Renders Distant Objects Less Distinct.For that reason the objects nearest to the eye should be drawn with strong lines and tones to indicate their nearness. Therefore, subdue the distant tints and intensify those appearing in the foreground. Direction of Outlines.As a general rule, any object with a decided form should have shading to correspond with the direction of outlines or to the general shape of the object itself ; ' thus, curved objects may be drawn with curved lines, the sweep of the curve corresponding somewhat closely to the form of the object. When these curved lines cannot be conveniently formed with one stroke the adjoined or overlapping should be as imperceptible as possible.

Tints Relatively Light or Dark.Fig. 6 illustrates the fact that tints are only relatively light or dark. In the first illustration, all of the branches seem quite dark because they are projected against a white background. In the illustration at the right, a mass of darker foliage is introduced ; the result is that, by comparison, the boughs and twigs, though in the same tone, or shade, seem light in color, except where there is a projection beyond the area of the foliage. This is a matter that should be kept in mind, for nearly as much depends on the scale and key in drawing as in music. Shadows Should Not Be Confused With Reflection.There can be reflected darks as well as lights. Thus, we are apt to speak of shadows in the water when we really refer to reflections. There can, of course, be shadows thrown into any body of water. Reflections are cast only on the surface of the water, and the surface is generally what we see. In fact, the less clear the light and water the more clear are the reflections. And in this case a shadow would hardly be seen. Because it is customary, we say, "Reflections in the water." Reflections, however, are on the water. Reflections are not affected in shape by any changes except by those on the surface of the water, such as ripples or waves. Reflections have the same perspective as the object causing them except that the former are inverted. Shadows Not Considered as Lines.In putting in shadows and tones, lines should not be considered as lines, but simply as part of the surface by which we endeavor to represent or render something in nature or as a result of imagination. The lines placed more or less evenly and close together are components of some unit or part of a whole. By such means we try to imitate nature. Where to Avoid Placing Lights.Every object under the influence of a single light receives it only on that surface which is exposed to its direct rays. Therefore, avoid strong lights on the shaded side of an object. The Comparative Values of Different Tones should be explained to pupils at frequent intervals. Fig. 7 is a pencil exercise in which the contrasting effect of a single tone is again shown by means of contrasting effects. Note that the prevailing tone on the telegraph post is the same throughout.

Yet, while against the sky, it appears as a dark mass, as, contrasted with the still darker tones of the wall, it is comparatively light. The drawing of the skeleton of the wreck of a small sailing vessel on a sandy beach (Fig. 8) shows the brilliant effects caused by a strong, direct sunlight on a light surface. The shadows are crisp and rather sharply defined, with small, clustered blacks accentuating the high lights. The shadows are concentrated and scarcely weakened by reflected lights. This drawing is not a "studio ' composition, but made directly from a sketch made on the shore of Lake Michigan several years ago. Foregrounds and Backgrounds.There is no absolute rule regulating the question as to whether the foreground should be darker in tone than the background; for circumstances, as to time and place, must be taken into consideration. Generally speaking, however, the foreground and middle ground should be the parts of the picture in which appears the greatest display of color or tone; where the darkest effects are shown. Suitable Contrast.It is, however, more a question of suitable contrast than anything else. In pictures where a single human figure or-a group occupies the foreground, the background should be light and merely suggestive in the way of details. The contrast is more generally produced by having the objects in the foreground dark and those in the background light. The lines in the background should, in certain instances, be much finer than those in the foreground, and with very slight, if any, accentuations. Avoid Flatness.The keynote of attractiveness in a picture is frequently a matter of contrasts. Flatness is an almost unpardonable fault. By introducing strong contrasts, flatness is avoided. By playing heavy lines against light ones, strong tones against weak ones, contrasts are produced. Practice Outline.The outline is of the greatest importance, frequently being complete in itself as a means of representation of form. To copy slavishly the outlines found in copies or nature is not altogether necessary if the general forms are preserved. Mass Drawing.In drawing, a knowledge of the masses will aid greatly in giving the general impression and in indicating the position and form of the various details. These masses should be shaded in the drawing to reproduce the tones as they appear to the eye. A soft pencil is best adapted for this purpose. A very limited range of tones is required to produce excellent results. It is best to draw masses not with the point of the pencil, but by holding it at an angle and drawing with the side of the lead. This is to relieve the mind of the impression of lines and to allow the mind to concern itself simply with the shape and density of the various tones of light and dark. It is a good plan to outline the various masses before filling them in, as this will enable the pupil to adhere more closely to the true shapes and edges of the masses. Easy Examples in Light and Shade.The examples in Fig. 9 show how, by simple means, the direction of the light may be indicated. In r may be seen the light coming from the right side ; 2 shows the light coming from above, and in 3 the light on the walnut is from below. The heavy lines in an outline or slightly shaded drawing should be made to indicate those parts which are against the light ; the light lines the parts n arest to the light. In the drawings of the tree trunks, light and shade effects are shown by opposite instances. In 4 the light comes from the right, in 5 from the left. Draw other objects from nature or imagination, such as a cup, a stone, an ink-bottle or top, and note the light and shade effects.

Accentuation in Outline Drawings.In outline drawings, this general rule may well be adopted, subject to exceptions dependable largely on the common sense of teacher and pupil: The strongest accents and broadest lines should represent the nearest or most important lines of the subject. Lines representing portions of the background or unimportant 'detail, should be drawn with lighter and less accented strokes. Accented lines can be taught profitably at the outset almost. Their use produces facility and strength in handling. The invariable use of unaccented lines is more or less offending, even to the uneducated eye. In the upper drawing the lines are even, monotonous. In the lower one accentuation is evident.. Which is the more pleasing to the eye?

Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14. Fig. i i is the beginning of the finished sketch, Fig..12 ; while Fig 13 is the beginning of the finished sketch, Fig. 14. When drawing Fig. 12, the pupil finished the foreground first, which looked strong at the time. Nevertheless, when the background was put in, with its tones similar to the foreground, the latter appeared weak. Fig. 13 shows the beginning of the other sketch, Fig. 14. In this

drawing the background was finished first and the foreground last. As a result, the foreground stands out strongly in contrast to the background. Whenever the background is put in first the impulse is to place strength in the foreground. By doing so an arrangement of strongly contrasting light and dark tones is more apt to be produced, giving to the sketch the ever desired effect of power and value.

|

Privacy Policy ...... Contact Us