Home > Directory Home > Drawing Lessons > Drawing for Beginners >Drawing for Beginners

DRAWING & sketching tutorials for beginners with these lessons that will teach you how to draw

|

GO BACK TO THE HOME PAGE FOR TUTORIALS FOR BEGINNING ARTISTS

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

Drawing for Beginners

that is close at hand—a tiny clump of white flowers with feathery foliage, golden disks, and silvery petals growing humbly near the shorn stubble of the cornfield. It is a wise selection. Being of a lowly habit, the flowers will not be tossed and stirred by the wind, and so worry you at the very outset of your task. Moreover, the flowers have simple forms. They resemble tiny umbrellas with long handles. Draw first the shape and curve of the slender stem, then the circular gold centre, then the mass ' shape of the petals, dividing up each petal later, noting their wayward manner of growing.

After this your eye probably will be attracted by the gorgeous berries of the woody nightshade twisting its jewels round the ash stump and fence.

Draw the post and paling before the entwining tendrils and stalks. Wide-flung circles and rampant growth such as these lead the eye astray. But if the upright post and the cross-piece are once fixed on paper, then we have two simple and solid shapes lending contrast to the delicacy of the twining stem. If you began by drawing the stem of the plant, your eye might be misled by its strength and sinews. The foliage is vigorous. There is no feeble indecision in the sweeping curves and twisted heart-shaped leaves. Sketch the looping curves of the stem, then place the leaves, drawing from tip to tip on the outside edges. The berries gem the a post in fanciful clusters, hanging from thread-like stems. Make the post firm and strong and shade it broadly. The richest tone, however, is reserved for the berries, and the leaves have a high polish.

It is undoubtedly a tempting subject for the brush. Mix your colours clearly. The berries will probably attract your first

attention. Try to get the rich tints glowing and bright, then the colour of the leaves, allowing for their transparency by laying the paint freshly and broadly, and, when dry, adding some of the deep greens and browns of the background.

Fig. 66. SKETCHING PLANTS. THUMBNAIL LANDSCAPE SKETCHES

In all probability you will be disappointed with your first efforts. The open air is one of the most exacting of conditions. The pure clear atmosphere reveals every blot and blemish. Your model challenges your poor attempts with its incomparable beauty.

Nevertheless, do not be discouraged, for you have this great encouragement, that if the painting or drawing looks at all passable out of doors it will look infinitely better within doors.

A clump of brilliantly coloured fungi is a delicious subject for pencil or brush, and one that is often found in the woodlands on a summer's day. What could be more simple in form than a toadstool, with its curved top and ridged surface beneath, and the bulbous-shaped stalky Being a rounded surface, one part will be lighter than another. Try to place the shading correctly. The edge of the fungus may be broken, chipped, splotched, or stained. Do not neglect any of these happy accidents. Dame Nature springs the most extraordinary surprises upon those bent on discovering her secrets, and if we arc lax in small matters we shall miss the beauties in larger objects later on.

A trailing spray of blackberry is a charming subject for brush and pencil alike. Sketch the direction of the spray, then the mass of each spray, then the direction of each leaf in the spray.

When the sun is high in the heavens and the colours are faint and sickly, use your pencil instead of a brush.

A bit of a fence overhanging a piece of rock or sandstone, or a fence topping a grassy bank, or a stile viding two fields, are equally interesting subjects for a sketch.

And here I must repeat myself at the risk of appearing wearisome. In no case do I wish you to choose necessarily the subject that I have discussed. My examples are chosen, first, because they are simple and direct ; secondly, because they are within reach of the majority of young artists ; and, thirdly, because they represent variations of themes found over a broad area.

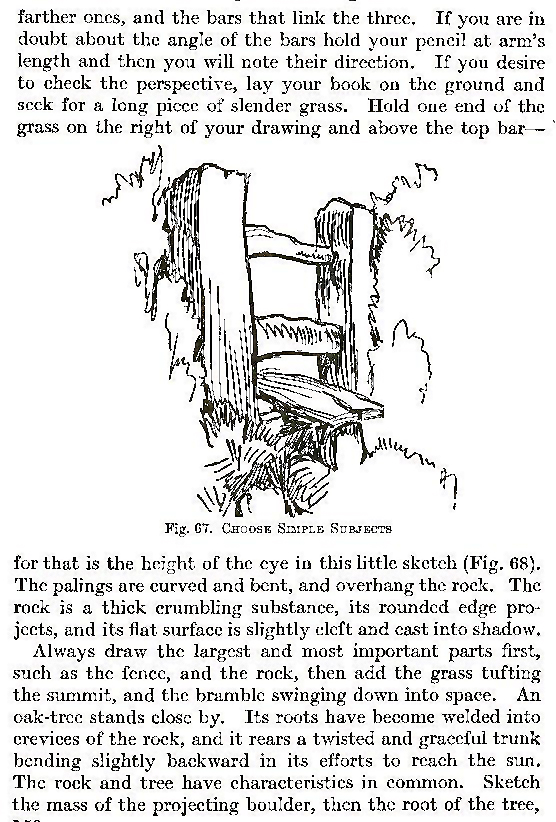

Draw the nearest upright post, get the direction of the farther ones, and the bars that link the three. If you are in doubt about the angle of the bars hold your pencil at arm's length and then you will note their direction. If you desire to check the perspective, lay your book on the ground and seek for a long piece of slender grass. Hold one end of the grass on the right of your drawing and above the top bar—for that is the height of the eye in this little sketch (Fig. 68). The palings are curved and bent, and overhang the rock. The rock is a thick crumbling substance, its rounded edge projects, and its flat surface is slightly cleft and cast into shadow.

Fig. 71. THE TWIG OF A POPLAR

Always draw the largest and most important parts first, such as the fence, and the rock, then add the grass tufting the summit, and the bramble swinging down into space. An oak-tree stands close by. Its roots have become welded into crevices of the rock, and it rears a twisted and graceful trunk bending slightly backward in its efforts to reach the sun. The rock and tree have characteristics in common. Sketch the mass of the projecting boulder, then the root of the tree, mark the girth of the trunk, and draw the tree, building up with big curves, and noting the snake-like twist of the slender branches. Mark the richest and deepest shadows, how the shadows break into shadow shapes of twigs, leaves, and grass.

Trees are difficult—that much is admitted even by Ian, who is devoted to his pencil.

" Oh, yes," said Ian, " I can draw horses, and men, and houses—but trees " and he paused thoughtfully.

To draw a tree from life, we must aim at the main structure. First draw the trunk, then the biggest anches, lastly the leaves.

There is a curious fact about trees that is worth recording, for it is often helpful when we are faced with the difficulties of grasping such a big subject. A branch of a tree will have all the characteristics of the tree itself.

Examine a small branch of an oak-tree—just a spray of leaves. Are they not sturdy, stout fellows ? Does not each twig strike out in an independent fashion—spreading strongly ? And is not the branch from which the twig is broken gnarled and twisted, stubborn and strong ? Walk some distance away from the oak-tree, then turn and observe it carefully.

Has not the tree the same characteristics as the branch, as the twig?

Compare a twig of the poplar-tree with the tree itself. Is not the twig the same pyramid shape as the parent tree?

It is a good idea to draw some twigs of a tree before trying to draw the tree itself. And this is an excellent subject when the weather is too cold to stand out of doors. Gather some bare twigs and carry them home and make careful drawings of the twigs.

When spring is approaching you will find delightful little subjects in the swinging green and red catkins and the soft down of the pussy willows, and autumn provides us with a wealth of clustering nuts. Which studies will help you with your drawing of the tree.

When drawing the branch of a tree look from one side to another side, from one angle to another angle. Build up the tree, as if it were growing under your pencil, with its rough-ness, nodules, and irregularities. Do not draw it too smoothly, like the polished leg of a table, but try to give it a natural sturdy growth.

Trees of a striking peculiarity are easiest to draw, as are people with strongly marked features. Such arc Scotch fir-trees with spiky needles, bony branches, and spiked trunks ; thorn-trees, small and twisted with the winds ; oak-trees that have braved many a storm, with lopped branches and thin foliage.

You will find it interesting to sketch clumps of trees with the brush, either in black or white or colour—a few tall elm-trees in a distant meadow, or a .fringe of fir-trees against the sky. This teaches you to observe trees as a whole, and also impresses upon you the varied silhouette of each type of tree.

Before we embark on the subject of landscape — for our horizon is broadening 1• rapidly — we might spend a few moments discussing the sketching of ruined castles and old houses, which so often form an ex-.5- cuse for an excursion or a picnic, and of which we usually desire to carry home some little memento in the shape of a sketch.

Fig. 75. A TREE DRAWN WITH A TWIG DIPPED IN THE INKPOT

Do not attempt complicated subjects. If the ruin is large and there are many

• turrets, many towers, flights of steps, and

• long passages, choose a modest fragment.

• An angle of a wall

against which twist the bony stems of ivy, one little window framing a patch of blue sky, a morsel of broken masonry, or a few steps—any of these will give you the materials you need.

A ruin invariably presents a crumbling, and softened, and somewhat elusive outline.

Rough in the whole mass, the general structure. Look for the highest point, compare the position of each thing with that point, then, having settled on the principal forms, look for the darkest dark and brightest light. Try to give an impression of the roughened surface. Draw the near shapes with care. If you sketch the masonry in the foreground with accuracy, then the parts that lie farther away can be more slightly drawn. The little bit of knowledge acquired by sketching something with care has a very solid value. Young sketchers faced with picturesque ruins are often tempted to try a tricky way of drawing.

We have all seen ruins ' touched in ' with sharp and telling bits of light and shade (apparently with ease and quickness), and we are fired with a desire to do likewise.

Believe me when I say that this is yet another pitfall for the unwary. The tricky methods of drawing never advance us one step.

We must sketch only what we see, and that with care.

Look also for the perspective (another thing that is often ignored when sketching out of doors), check the top angle, and the base of the arch, also the fragment of carving, and the window in the wall with the near and projecting masonry.

Once we are fairly embarked on the subject of ruined buildings and trees, we feel more capable of trying real landscapes on a larger scale.

As an introduction to this more ambitious task, try your hand at thumbnail sketches. By thumbnail I mean tiny impressions of fairly large things, small houses, small trees, and the broadest indication of the curve of the ground, of fields, hills, and hedges. Not scribbles, but honest though minute sketches marking the chief characteristics : the lie of the ground, the position of the houses, the shape of roof (whether pointed or flat), the comparative size of the trees or shrubs, the tint or tone of trees, grass, roof, and walls. (See the examples in Fig. 66.)

Needless to say, distance does lend enchantment to the view in these thumbnail impressions, and they are far easier to draw when seen from a long distance. They are useful, too, for the few minutes' wait at a railway-station, or the short space of time spent at places when motoring. We can seize on a few of the salient or chief characteristics of the landscape and jot down tiny little pictures of houses and trees, hills and valleys, cliff-end and sea. The concentration necessary for these sketches will help us to grasp the chief characteristics of larger sketches.

A barn on the top of a sloping field, with a horse cropping the turf, and a morsel of a fence is as simple and direct a subject as one could find. Begin by sketching the slope of the ground, on which erect the shape of the barn, with its pointed roof, then the upright palings and short bushes, the horse with bent neck and the barrel shape of its rounded body.

Then as to the colour. A soft yellow light pervades sky, barn, grass, and horse, and on this float the rounded misty shapes of the grey clouds. The golden-brown roof is touched with cooler grey shadows on the near side, and the grass mingles with the reddish soil, something the same tint as the barn. The hedge is olive deepening to brown, and the flank and neck of the horse is a richer brown and olive sharpened with darker tints.

Light and shade out of doors is often most bewildering to the young student. The light is suffused, the air is clean and penetrating, shadows flicker and change.

Before beginning a sketch try to decide on the most definite bits of light and shade. Make a thumbnail sketch in the corner of your book if you will, in pencil or charcoal. Say to yourself, " The sun was out, the rays shone from that particular angle."

Should you find the shadows and rays vanishing before the approach of large clouds, wait till the clouds pass. If, instead of passing, more clouds appear, then begin another sketch, for those clouds change the whole effect of the landscape. And how much they change it can be proved by referring to your thumbnail sketch.

Sketching on the seashore raises a fresh crop of difficulties and delights.

Boats are not easy things to draw when lying on the beach. " And that is the reason," Audrey explains, " why I prefer to draw them in the water."

Audrey is wily, but she doesn't altogether avoid her difficulties. If we are spared drawing the curve of the keel seen when the boat is exposed on the pebbles, there is all the rigging to lead us astray when the boat is in the water.

Moreover, we must know something about the shape that is hidden by the waves. As it is necessary to know the shape of the limbs covered by the clothes, and the branches covered with the leaves, so is it essential that we should know something of the build of the boat.

Should our artistic eye be attracted by the rich tints of the sails of fishing smacks or long-shore boats, we must be careful not to neglect the rigging and shape of the sails.

I have a distinct remembrance of five drawings by five little ladies of a fishing smack with sails exactly the same shape fore and aft. Compare one sail with another sail. Begin by drawing the long sweeping curves of the hull, and then the angle of the mast. With these two facts carefully noted you won't go quite so far astray.

Fig. 80. STUDY OF A BOAT

A beach, however, has a lot to offer besides the boats. There are the capstans, and the high black houses where the fishermen store their nets and tackle, and the lobster pots, and the heaps of coiled ropes. There are the rocks with their brown and mossy sides reflected in limpid pools ; crabs ; shells of all descriptions ; starfishes most obligingly lazy and quiet sprays of deliciously coloured seaweed ; sand castles, wooden spades, and scarlet buckets.

The beach is full of interesting little colour subjects. The air is clear, and the water reflects the light ; bright caps and frocks, sails and seaweed, and the striped tents and scarlet buckets are all most attractive.

All our former discussions, our thumbnail sketches, pencil and chalk studies, and small landscapes in colour will render sketching by the seashore easier.

If we wish to sketch people sitting on the beach, or children playing, we shall have to be very rapid. It is wisest to sketch the stationary things first. If we desire to sketch Mollie or Rosemary by their tent or climbing the breakwater or rocks, do not let us waste time waiting. Sketch a bit of the tent, the breakwater or rock, then when Mollie or Rosemary appears you will be prepared. Also, and I speak feelingly on the subject, they may dart away before you have painted the colour of their shoes, belt, or even dress—if so, write the colour tint in the margin.

But with the distant promontory and the glossy procession of rocks stretching into the sea, you will happily find something at rest. Only, remember this, never begin a sketch in the morning and finish the same at night. The light will be wholly different.

Sketch a morning scene by morning, a noonday scene at noonday. If you have not done all you desired to do during those periods of time, put the sketch away until those hours recur. It is highly improbable that you will see the same effect again, for that is at once the bane and delight of sketching—its never-ending variety.