Home > Directory Home > Drawing Lessons > Figure Drawing for Children > Drawing Children's Arms, Hands, and Forearms

HOW TO DRAW A BABY & child's ARMS, HANDS, AND FOREARMS WITH STEP BY STEP DRAWING LESSONS

|

GO BACK TO THE HOME PAGE FOR TUTORIALS FOR BEGINNING ARTISTS

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

THE ARM, FORE-ARM AND HAND

Having so far regarded the arm, fore-arm and hand only as a section of the whole figure, we must now study them in detail.

The arm proper is the part from the shoulder to the elbow, the fore-arm that from the elbow to the wrist; these two sections, with the wrist and hand, are usually referred to collectively as the upper extremity.

The upper extremity is, on the whole, a small division, its full integumentary outline making it sewn shorter than it is, and even appearing to interfere with its ready use. This is notably the case when the abdominal line is well rounded as when a baby is seated on the lap of an adult. Owing to the full integumentary development no deep indentations occur in the outline. Where one might be expected, a fold, or extra fullness of flesh, will be found to fill the depression. In the chubby child hand and arm this is particularly noticeable.

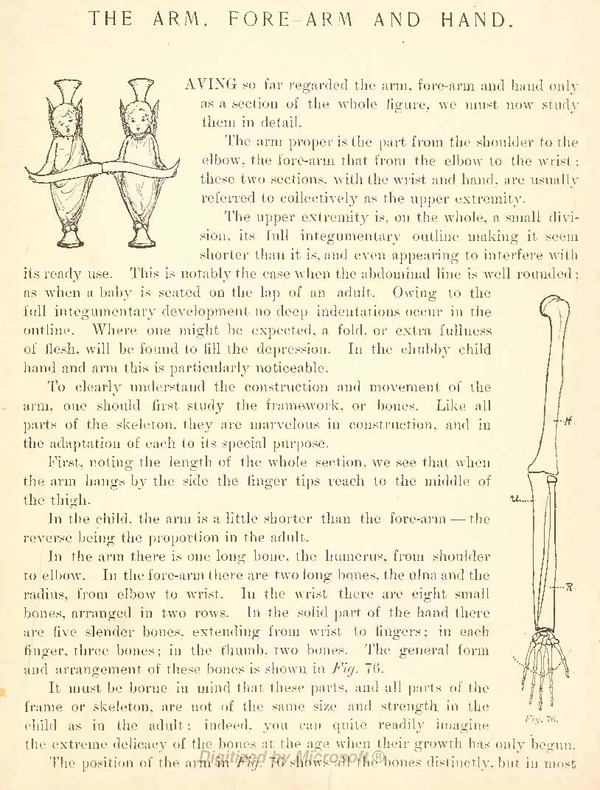

To clearly understand the construction and movement of the arm. one should first study the framework, or bones. Like all parts of the skeleton, they are marvelous in construction, and in the adaptation of each to its special purpose.

First, noting the length of the whole section, we see that when the arm hangs by the side the finger tips reach to the middle of the thigh.

In the child, the arm is a little shorter than the fore-arm — the reverse being the proportion in the adult.

In the arm there is one long bone, the humerus, from shoulder to elbow. In the fore-arm there are two long bones, the ulna, and

the radius, from elbow to wrist. In the wrist there are eight small bones, arranged in two rows. In the solid part of the hand there are five slender bones, extending from wrist to fingers ; in each finger, three bones ; in the thumb, two bones. The general form and arrangement of these bones is shown in Fiy. 76.

It must be borne in mind that these parts. and all pails of the frame or skeleton, are not of the same size and strength in the child as in the adult ; indeed, you can quite readily imagine the extreme delicacy of the bones at the age when their growth has only begun.

Note carefully the proportions finger tips, is twice the opposite the longest. or part of the hand is lonosof the hand is longer part, than on the back, or the length of the fin-side than on the inside. the palm presses part way of the hand : that the length. from wrist to width, as that second finger. the solidest : that the solid part, on the inside. or palmar dorsal part.

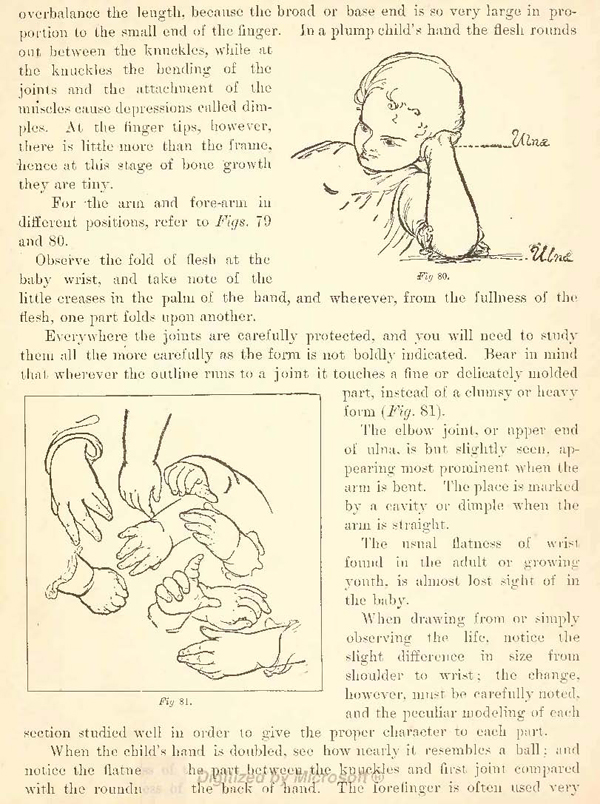

The fingers, especially of a baby or young are always larger at the base. where they start from the solid part of the hand, than at the tips. The width often seems to overbalance the length, because the broad or base end is so very large in proportion to the small end of the finger. In a plump child's hand the flesh. rounds out between the knuckles, while at the knuckles the bending of the joints and the attachment of the muscles cause depressions called dimples. At the finger tips, however, there is little more than the frame, at this stage of bone growth they are tiny.

Observe the fold of flesh at the baby wrist, and take note of the little creases in the palm of the hand, and wherever, from the fullness of the flesh, one part folds upon another.

Everywhere the joints are carefully protected, and you will need to study them all the more carefully as the form is not boldly indicated. Bear in mind that wherever the outline runs to a joint it touches a fine or delicately molded part, instead of a clumsy or heavy form.

The elbow joint, or upper end of ulna., is but slightly seen), pearing most prominent when the arm is bent. The place is marked by a. cavity or dimple when the arm is straight.

The usual flatness of wrist found in the adult or growing ( youth, is almost lost sight of in

the baby.

When drawing from or simply observing the life, notice the slight difference in size from shoulder to wrist ; the change, Fig 81. however, must be carefully noted, and the peculiar modeling of each section studied well in order to give the proper character to each part.

The comparatively straight lines, and the angles of later life. are hardly hinted at in the child-figure, the outline: from all points of view, being made up of multitudinous arcs or segments of circles.

It would be well if, when working from life, the student could feel that each division of the figure had an individuality that claimed his conscientious study : as if each part were a person, or had a personality ; for to slight the beauties or peculiar features of any section; is to rob it of i claim for appreciation.

Privacy Policy ...... Contact Us