Drawing in Pen and Ink : Techniques for Pen Drawing

How to vary tone in ink drawings

The technique of the pen is vastly different from that of any other tool the artists use, and the work done with a pen is consequently very unique. By nature it is a much harsher and a less flexible instrument than either the pencil or the brush, even though pens have come a long way. A pen drawing has a distinct individuality, no matter what kind of a technique is used, fundamentally because of the manner of getting the various tones and shadows, which is different from that in the other mediums generally used.

In pen drawings, the ink goes on to the paper in its full strength, unlike with other mediums. In other mediums, you either add water or white to get lighter tones, however with pen and ink, you use the white of the paper to get lighter tones. To get a half tone, or quarter tone, or whatever tone is desired, the intensity of the color must, of course, be reduced, but this reduction of tone is produced by using the white paper as the reducing medium. Instead of water or white being mixed with black and then applied to the paper, the solid black is put upon the paper, which itself is used for the white and mixed with the black as the latter is placed upon it. This is done by means of lines, stipples, etc. (which will be described later), all of which, in some form or other, allow the white paper to show through and, by mixing with the ink, produce a reduced tone of black. For a dark or heavier tone, more ink lines are used, for a light tone more paper shows through, the ink lines being thinner or farther apart. If we take a space say one inch square and color it solid black, there is a black spot one inch each way; if we leave it untouched, then there is a white one; if we cover it with black lines that are the same thickness as the white ones in between, then we get a half tone; if with lines that are three times as wide as the white, it is a three-quarter tone; if the white spaces are three times the width of the ink lines, then it will be a quarter tone. The ratio of the black lines to the white spaces of paper that shows through between is the factor that governs the tone, and, as the tones of a drawing vary greatly, the heaviness of the lines and the proportion of the white paper must, of necessity, vary also.

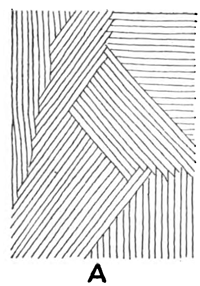

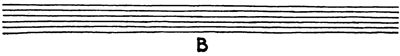

Light Tone

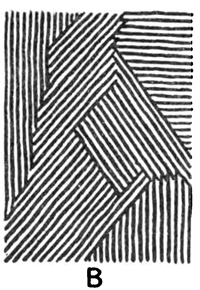

Dark Tone

A, for example, shows a light tone, while in B a dark one is seen. They are both tints made by lines running in the same direction, and of the same character. The difference in tone is obtained by the difference in the thickness of the lines used, and in the size of the white spaces showing between. In A, the black lines are thin and the white lines between thick; while in B, the black lines are much thicker and the white ones thin. In other words, if the amount of black on a square of the same size of white paper is more in B than it is in A, B is necessarily the darker tone. More ink, a darker tone; less ink, a lighter one.

Line work

As the most popular and as the style in general use, lines should be considered first. They fall naturally into two kinds—loose lining and regular lining.

Loose Lining

Loose lining is a style wherein the movement of the hand and fingers is largely automatic; it is drawn quickly, and with no great effort made to keep the lines equidistant, though a practiced artist will instinctively draw them fairly even. Loose lining can be created simply by moving the fingers and hand back and forth over the paper. More pressure on the pen will, of course, make a heavier line; less pressure, a lighter one. This is the same method as in writing, a heavy pressure spreads the point of the pen and makes a darker line.

Regular Lining

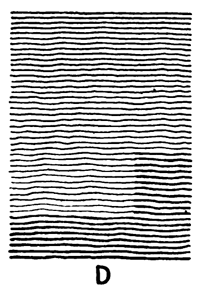

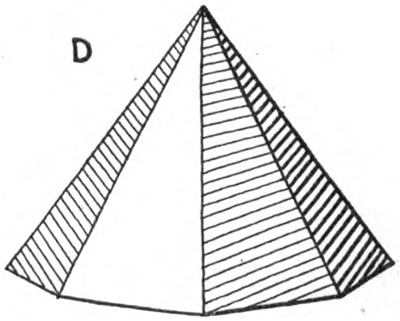

D shows a square of regular lines, which is drawn in a very different manner from C. The direction of every line is carefully watched, and the lines are “drawn”; that is, they are directed with precision to keep them the same distance apart and the same depth of color. The lines should be mechanically perfect in direction, thickness, and separation. When a darker tone is required, as at the bottom, make the lines thicker; for a slightly lighter, make them thinner or farther apart. It will be noticed that there is a slight gradation of tone in the square.

Crosshatching

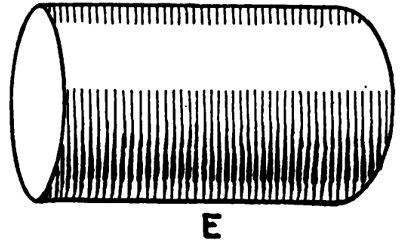

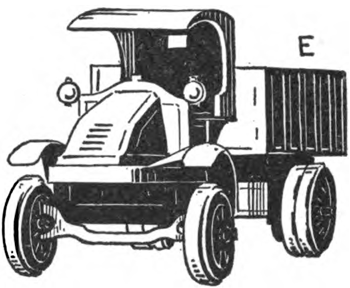

E shows a square of lines crossed by other lines. This is known as crosshatching, and is sometimes used for the purpose of darkening a tone already laid down. Crosshatching is seldom seen any more, except for certain special uses or to add a little variety of technique to a drawing. For an ordinary tint, it is hardly ever used, modern practice demanding that the tint shall be made by placing the lines closer together, or by making them heavier. Sometimes, in the darker parts of a drawing, where the tone needs to be very heavy, yet not black, and the black lines have been made as wide as is convenient or as will look well, crosshatching may be practiced. In this case, it turns the thin, white lines into small, white dots, and makes the tone darker.

One point must be made; namely, that one line by itself is always black, while two or more make a gray tone. This comes, of course, from the fact of the white paper’s showing in between them. After a tint is started, every time we draw one line, we draw two—the black one in ink, and the white one formed by the space between it and the last one, so, while a single line will show black on the white paper, two or more of the same thickness will show gray, because they have white lines mingled with them, and, as explained previously, the different proportions of the white and black lines are what make the tint or tone required. It is just as necessary to watch the white line as it is to watch the black one.

Irregular Stippling

Now on to stippling. A stipple is a dot; an irregular stipple is a tint of irregular dots, as in F, where the pen just dots them on the paper in an irregular order, and also, probably, in uneven sizes.

Regular Stippling

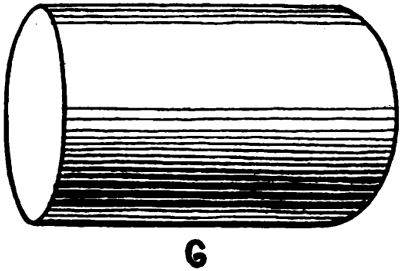

A regular or mathematical stipple is a series of regular dots of given form, usually drawn in a series of curves that blend into each other, as seen in G. These stippled tints can be made darker, the same as a line tint, by making the dots heavier and the white spaces between them smaller, as shown in the lower right-hand corners of both squares.

Manipulating the Your Art Materials

The angle of the board, in pen drawing, is something that every artist must settle for himself. As in pencil drawing, it is much easier to see and judge the work if held upon an angle, tilting upward at the back, but this angle cannot be too much, or the ink will not flow from the pen to the paper. If the tilt of the board is too great, the pen is too nearly horizontal for the ink to flow freely, and it is very inconvenient and difficult to work in such a manner.

Hold the pen in the same manner as the pencil. Be especially careful not to grasp it too tightly, press too hard with the thumb, or hold a stiff wrist. It is even more important in pen work than in pencil work that these directions should be followed, because of the need of making wider, thinner, variable, or swelled lines (to be described later). Hold the hand a little to one side of the line to be made, not directly in front. For a thin line, turn the pen slightly sideways; for a heavier one turn it more to the front, as it is difficult to spread the nib and make a heavy line if the pen is held sideways. For short lines hold the pen well down toward the nib; for longer lines, farther up the handle, and do not try to make too long a line at one stroke. An inch and a half should be the extreme limit till one attains some practice. The easiest kind of line to draw is one beginning at the upper right-hand corner of a square and continuing to the lower left-hand corner; the most difficult is one beginning on the upper left hand and running to the lower right hand. To draw the latter successfully, the paper must be turned. Do not try to draw backwards or the pen may spatter, or the points may Cross.

Line practice.

The first things to practice with a pen are lines and curves so as to attain a sharp and even black line. When this is done successfully, try to draw two parallel lines together as in A.

Then try to draw six or seven parallel lines, so as to form a tint, as in B.

This is the first step in making line tones, and it requires considerable practice to follow one pen line with another, so as to make an even, regular tint. The lines should all be of the same thickness, and also equidistant, so that the white lines between will be the same thickness. When doing work of this kind, or, in fact, any work in pen and ink, always be careful to draw toward you, as drawing pens are not made for working in any other manner. Turn your drawing in any way you wish so as to make it convenient to draw your lines in this way.

How to Make Two Pen Lines Look Like One Pen Line

As stated above, it is neither advisable nor good practice to attempt to make too long a pen line at one stroke. If the line is to be at all long, then the pen must be raised, the hand moved forward, and another start made with a new line. This line must meet the old one, however, without showing any mark or break, and the whole line must continue in a perfect, unbroken line, without any thickening at the place where they join or any sign of breakage or spot where the pen is put upon the paper again. This is solely a matter of practice and of long practice. No one can expect to make a long line the first time, or the first ten times, without showing some indication of where the different stops have been made. It is useless to expect to do it.

Don’t Use a Ruler to Make Your Cartoons and Illustrations

It may be asked if there is any reason why this trouble should be taken when a straight line can be readily drawn with a straight edge, or a series of lines, so drawn to form a tint. This can be done is, of course, true, but it is often very bad practice. Even a boundary line is often drawn in free-hand, because of the different appearance of a ruled line and its mechanical character. A tint formed of ruled lines is hard, inexpressive, and of purely machine-made appearance. The first line of A is drawn with a straight edge ruler, the following ones are drawn without a ruler, and the difference in character is easily seen. The line is dean, sharp, true, and straight, yes, but the human touch is missing and loses the special character to it. Six tints drawn by hand by six different artists may show six slight variations in handling; six tints drawn with rulers will all look alike. There is no way to express personality with a ruling pen and straight edge.

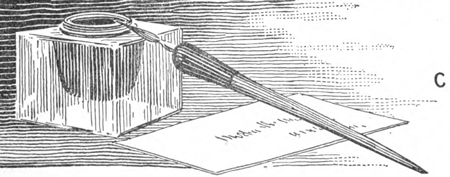

It is always wise for a beginner to draw the shading lines in pencil before putting them in with the pen. In C a pencil sketch is shown with the lines marked that are to be later drawn in with pen.

D is the finished pen drawing. Of course, this method is largely dropped when the artist becomes an expert; but it is, at the beginning, very necessary.

Showing shape by line direction

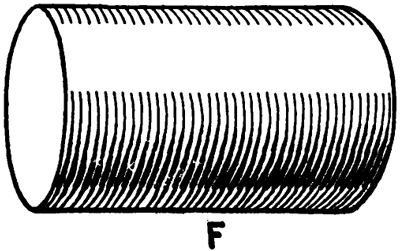

The method of running a line to express a certain shade or shape and the direction of the line forming the shadow is very important. It may be taken as a general rule that the direction of the line forming the shadow should follow the shape, and this is shown in Figs. E, F, G, the outline of which is the same in each case.

In E no notice has been taken of the shape, otherwise than as it casts a certain shadow. The shade lines have been simply run straight vertically, the sole means for showing the shape being the different degrees of tone and thickness in the lines, and the perspective of the ends. If these ends are covered, we get no effect of perspective in the object, ,which looks as though we were gazing squarely at the side, instead of partially from one end. It simply becomes a part of a rounded object set in front of us.

In F the tone quality is the same, the shadows fall in the same places, but the lines composing them conform to the perspective shape of the cylinder instead of ignoring it, as in E. Thus it makes no difference where the eye falls upon the surface, we appreciate the fact that the cylinder is in perspective and viewed from one end. If we cover up the ends, it makes no difference, and if we imagine this cylinder to be part of a group, with both ends covered, we can readily get the reason for the point made above, and see why the direction of shade lines is sometimes a matter of great importance.

G shows a third method of lining which is useful in some cases and can be drawn in less time, but by far the best manner of shading for general work is that shown in F.

A shows the effect obtained by line direction very well. The whole effect of this drawing is obtained from the direction of the lines. They are all of practically the same thickness and the same distance apart, form a flat and even tone, and have no shadow variation at all. Yet the texture shows very plainly; we are in no doubt of the object we are gazing at, we know that it is a piece of wood, and the effect of the grain is obtained solely through the direction of the lines.

Direction of lines is also a question of deep moment in groups, as at C. Note the way in which the lines help the effect, by separating the various articles from each other. The background lines are run horizontally, those of the table horizontally, while those on the bottle and the pen conform to the shapes of the objects. The various objects are thus separated or individualized not only by the differences of tone, but also by the differences in line direction. Technique of redrawn lines. It is not always possible, especially for a beginner, to draw a line of just exactly the proper thickness to make a certain tone required.

At B we have the teapot, resting on a cloth, with a trifle of tone for background. The teapot, being porcelain, is hard, and a hard, firm line should be used for it; the background is neutral, the cloth soft and a trifle darker. Going over this latter in spots to get a deeper tone, the added lines give a different softer texture, and teapot, background, and cloth are all separated, as much by the difference in the texture of the lines as by the tones which they make and the direction in which they run. It must not be thought that the lines in the teapot were drawn exactly the right thickness first time over, but in thickening them up great care was taken that there should be no irregularities of width or edge.

Line texture

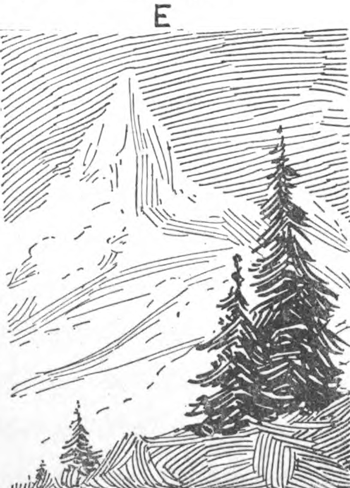

The difference of texture in the lines composing a tint is something that the artist needs to watch continually as in the case of the teapot. Note the little scene in D. The tone of the sky is flat with a smooth, even line; those composing the clouds are broken and give a fluffy appearance, while those in the treetops are strong, heavy, and vigorous. It will be noted that there is a great difference in texture as well as in color and direction between these three parts. As they are now drawn, there is a vast difference in effect between each object in the picture, and each stands out positive, distinct, and with artistic effectiveness. This ability to change the technique and direction of the lines is one of the qualities of the pen, and should be cultivated. It sets this medium apart from every other one, and gives it an individuality and character entirely its own.

Lastly in E is shown another type of line, light, sketchy, and graceful. There is apparently very little to it, yet it is far more difficult than the other illustrations shown above, because every touch must tell a story every time the pen is put to paper, it must do exactly the right thing, and yet, with all these requirements, the work must be done quickly, easily, and with absolute confidence, or the effect of light grace that is its charm will not be obtained.

Parallel lining

In addition to the styles of lining illustrated in the above pictures, there is a type of regular lining that has been carried to a high degree of excellence both for illustrative and other purposes. The different tones are obtained by parallel black lines of varying thicknesses, closer or farther apart as required, every one of which is drawn with care and thought and shaped carefully, is free from any irregularities, and follows the neighboring lines in perfect parallelisms.

Swelled line

In A is shown a square of variable tone, in what is known as a “swelled” line; that is, the line is made thicker, where the tone is to be darker, by “swelling” it. This is done by putting more pressure on the nib, and has to be done very carefully. Beginning at the thin end the pressure is gradually applied, making the black line thicker and the white one thinner. At the heavy end and the lower right-hand corner of the square, as it would be impossible to swell the pen to this extent, the lines are thickened by being drawn over.. It would be almost impossible to draw lines as heavy as these in one stroke, and still keep thin, even white ones between, so the two sides of the heavy black lines are drawn, and then the space is filled in with ink. This has a tendency to make a hard, mechanical line, because both sides of the line are very sharp. It will be noticed, also, that the white lines composing this tint are true in form, and that as the black lines grow evenly thicker, the white ones are evenly reduced in thickness.

The white line

The study of an even, regular line tint brings us to the study of the white line. When drawing a tint, an artist is really drawing two lines every time he draws one; namely, the black one in ink, and the white one between it and the last black one. From now on this white space, left between two black lines, must be understood as a white line, and the reader should thoroughly accustom himself to seeing it and understanding it in this way. This is readily understood, but what is not so plain is the fact that this white line (the white paper left between two black lines) is of equal, possibly even greater, importance than the black one. The general tendency in pen drawing is to put in the black line, and to a certain extent ignore the white one, leaving it to take care of itself, depending solely upon the black one for the color and upon crosshatching, etc., to get the darker tones required. This is absolutely wrong, especially where the lining is regular in character, and largely explains the failure of many artists to secure deep, rich tones.

Take a piece of white paper and make a black line upon it, as in B.

and then

Take a piece of black paper and make a white line of exactly the same thickness upon it, as in C

You will notice that the white line will show up stronger and more prominently than the black line, even though, in reality it is no thicker or heavier. Therefore a few white lines on a black portion of a drawing are of more value in changing a tone than an equal number of black lines of the same thickness on a white part. Because, of all of these facts, it is very necessary that the artist should watch the thickness of his white lines very carefully. When drawing the black one, he must see that the shape and thickness of the white one are taken into as full account. This value of the white line is a fact readily understood in wood engraving, but is not by any means so generally recognized in pen-and-ink drawing, notwithstanding the fact that it is of just as much importance for many reasons.

Use of white

It is sometimes very difficult, to leave a thin, sharp, white line by drawing around it in black ink. One reason is that a light irregularity of the pen may cause a wavy edge, and, in this case, many artists find it handier to fill in the space solid black, and draw the white lines on top of this black in white, either with a pen or brush. To do this, a heavy, opaque white is needed, one that will flow freely and yet be solid when it is dried. There are several whites made for this specific purpose which answer the requirements perfectly. It is advisable to save a special pen for drawing with white.

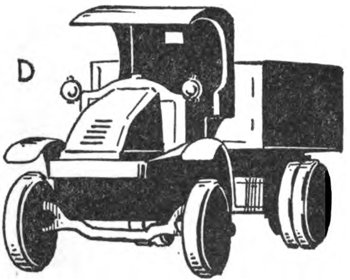

To make this subject of white lining plainer, a truck is shown at D, which, apart from a few short outlines, is all in solid black masses.

E is a duplicate of the same truck, but with much detail added in the shape of white lines, etc. This truck, E, was drawn in exactly the same way as D; the same outlines, black masses, and so on, and the added work, the lines, detail, spokes of wheels, lines on the side of the hood, on the body, white lines on the seat top, and over the axle, were all drawn with white upon the solid black. This was used in a pen in exactly the same manner as if it had been black ink.

Note : the fact that the lines vary in thickness and distance apart, just the same as if they had been drawn with black ink, and that the black lines also vary in like manner—that is, in thickness and distance.

Once again let us impress upon the reader that it is the combination of black and white lines that form a tint, and that the relative proportion of these to each other will make the depth of color in that tint. It is impossible to make this fact too evident, or to drive it home too strongly, and the fact holds just the same, whether the black lines are drawn on white or the white lines on black.

Outlining by shading

One of the most difficult things to do in pen and ink, and one that requires both careful work and practice with lines before attempting, is the drawing of a full shaded piece of work without the aid of outlines or sharp definitions between shadows, such as D, but with more complicated detail in tone and quality. A drawing where the tones blend into each other, more or less, where there is much detail or many differences, and yet where these details must not show too hardly or the differences too prominently, is the kind of pen drawing that taxes the artist’s skill to its limit.

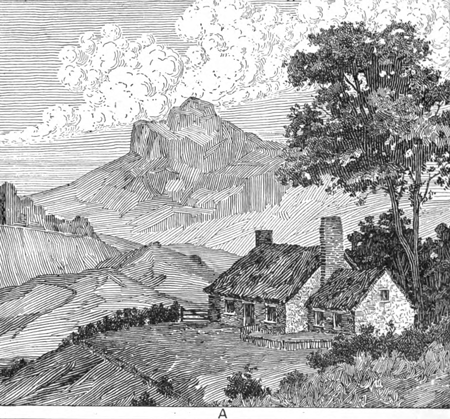

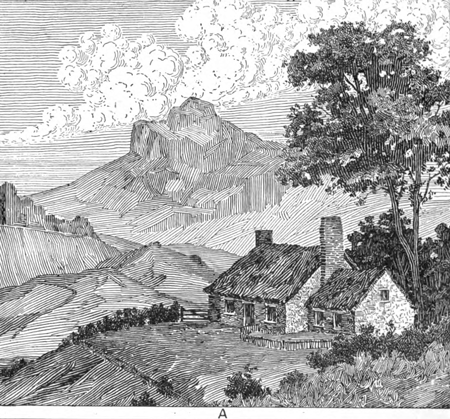

A drawing of this type is shown in A. There is practically nothing in outline, and when an outline has been put in, which is seldom, it is worked into the shadow lines so that it shows as one of them, and not as an outline. This is an exemplification of what has been said before, that one line shows as black; a number of the same lines, as a tint. In a drawing such as A, we are drawing tints and tones, not outlines, varying the style of line to fit the object represented. In the sky, for example, there is a flat tint for the basic blue color of the sky, with the white clouds of an entirely different kind of line floating on it. Then, again, in the ground we have many tones, some of which are fairly dark, some much lighter, but all blending into each other as they do in nature, or simply separated by difference of tonal quality, helped to a great extent by difference of quality or direction of lines composing them. Where there is any sharp distinction of tone it is obtained by the juxtaposition of one mass against another, just as it would be in nature, not by a harshness of line or outline. The trees are somewhat darker in tone than the rest of the work, but they are trees in masses, not in detail, except in places where a small amount of accentuation will help to explain the general composition of the mass.

This is the true secret of pen-and-ink drawing, the drawing of tones and masses, not of lines. The lines are simply a medium for getting the masses, and we must remember that it is the masses we are aiming to draw. The lines are simply the means by which the masses are made. Combination of methods in a single piece of work. Let us consider this drawing in detail, and the means used to place its different phases of tone and quality upon paper with pen lines. The sky background is drawn in parallel lines of an even thickness, an even distance apart, though varying in color, as it approaches the horizon. Upon these the clouds are drawn with a freer, more irregular line, to give an appearance of fluffiness. Against this sky, the hilltop must stand out darker and more massive, and this is drawn in the same style of lining and of varying depths of color and direction. The same lining is used in the middle distance, being changed somewhat in style, according to the requirements of the details in the landscape, or the character of the objects represented. Against this middle distance, the foreground looms up, the side of the hill being drawn in much the same style of line; but the yard within the fence is drawn with a few differences of darker tones and a slight variance of texture by breaking the lines here and there and allowing a white spot to show at the break. The wonderful difference in the appearance of a tone made by this mere breaking of a line shows somewhat plainer in the front of the chimney The thatched roof of the cottage is drawn with more variance in the thickness of the lines, and the same is true of the walls, excepting that the spaces on which the lines change direction are very much smaller. The grass and weeds in the right corner are merely various curved lines run in the manner that such vegetation would fall. In considering the hedges we have a style of lining different from any used heretofore; it is that shown somewhat darker and heavier in the lines, and it will be noticed how this difference in texture and method makes the hedges stand out from the surrounding work. Of course they are darker, but it is not only the tone but also the change in character that sets them apart. This same crosshatching is used in the large tree, only the lines are shorter and, in some of the lighter places, slightly curved. Lastly, the mass of dark foliage back of the cottage was drawn in solid black, and the white lines drawn in with white. The gable end of the main part of the cottage was crosshatched with white.

The drawing of this landscape has been analyzed very thoroughly and in detail, to give an idea of the many ways of drawing lines that will enter into a drawing, not because they may be all absolutely necessary, or because every artist would use the same methods. The style of work mainly used is solely an individual matter, and most artists will have their own individual style, and work accordingly. It is, however, very necessary that all these styles of technique should be understood, so that, when drawing a piece of work, the particular style that seems fitted to any particular part may be grasped at once and used; and this grasping and using should become almost a matter of instinct.

Now you have a good grasping of pen and ink drawing techniques. Start practicing to get your pen lines perfected.

Technorati Tags: pen and ink, pen drawing, ink drawing, drawing in pen, drawing in ink, pen drawing techniques, ink drawing techniques, how to draw, how to illustrate, pen illustration, ink illustration, drawing techniques, how to draw

Hi Robert I am one of your fan in art but I am eager to learn to draw with pen art is fun thanks*

I use to draw a lot about 30 years ago, but I became interested in astronomy which took up just about all of my time. Well my doctor says staying out late at night in the damp air is not good for me, and lifting my heavy equipment also is not good for me. So I’ve decided to give up astronomy and go back to drawing and painting (water colors). This site proved to be just the ticket to get back into art. I am 80 years old but I think I can handle the pen and brush. I did not know that I had become so rusty at drawing. This sote is putting me back on track. I will draw most of the subject matter as it has really helped. Thank you ever so much.

Hi Robert. Sorry to take so long to get back to you. It is never too late to get back into art. It is just what the soul needs to uplift your mood and make life a bit more fulfilling. Glad that my site helped you!!!!

I really like your tutorials and web site. But…. I do find the Draw While You Learn side bar box annoying. I minimize it, but each time I change pages, it comes back up. I think its a useful tool, but keep it minimized until needed.

Hmmmm….that does sound annoying…I will think of a way to stop it from doing that. Thanks for letting me know.

I was looking for something like this on the internet and almost gave up on the matter till i found this!

Thank you! I love you so much =,)