Home > Directory Home > Drawing Lessons > Drawing for Beginners >Kids Can Learn How to Draw by Drawing Simple Household Items

Learn How to Draw by practicing drawing simple subjects such as toys, dolls, feathers, and leaves

|

GO BACK TO THE HOME PAGE FOR TUTORIALS FOR BEGINNING ARTISTS

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

How to Begin. Simple Subjects for Drawing and Painting

Do you like painting ? Does drawing interest you ? Have you a pencil, a box of chalks, or a paint-box? Because, if you have even one of these things, you can open the door to such happy times. Take a sheet of paper, or open your sketch-book ; pick up a pencil. Now what shall we draw?

Some children bubble with odd fancies ; men, horses, fairies, dogs come tripping to their minds ; but you and I are not so sure. We will choose something simple, something interesting.

What of a leaf, an ivy leaf ?—for that we can easily find whether we live in city or country.

It is a quaint shape when we come to observe it closely. Would you call it a long, square, or round shape ? I should say that it resembled a heart.

Then we will draw a heart-shape. Next we see a large vein running through the centre of the heart. It extends from the very tip of the leaf to the stout little stalk which eventually fastens itself on to the main branch.

Now we had better mark the chief points of our leaf, which are three in number. And also there are two or three a trifle smaller. These we also draw. And we note that the large central vein is met by two smaller veins, and that these, with two more, radiate from the stalk.

Turn the leaf and look at its back and see how wonderfully these veins converge to the stalk.

Put in some of the veins lightly and carefully, choosing the biggest and the most important.

Next we should note that the light comes from one side, and the side farthest from the light is in shadow. We might shade the edges of the leaf with our pencil and sharpen and shade the strongly curved stalk, and any other part that needs to be strengthened.

You may say that you live where there are no ivy leaves. Then take a maple leaf, a sycamore, or a chestnut; any leaf at hand. I am not laying down any hard-and-fast rules, but merely trying to help you with something that you want to do.

If you prefer it, draw a shell or a feather. I suggest these particular things because they are simple and easy to draw, and within the reach of most people.

A feather can be studied on the same lines as a leaf, presuming that it is a well-formed wing or tail feather—a not-toofluffy affair. First observe its general shape. Elongated—oblong, is it not ? Then draw in an oblong shape. Next notice that it is broad at the bottom end, and that it inclines to a rounded point. We will shape off the side tips.

Next we trace the main stalk or stem from which the plume spreads. Observe the separating of the plume on one side, the crisp firmness of the narrower vein, the fluffiness at the back of the thick stem, and the solid firmness of the stem itself.

We can work this with a pencil and trace the beautiful marking on the feather, or we can produce our paint-box and try to colour your drawing. It is an excellent plan to hide the model from sight, and see how much, or how little, has penetrated our brain.Afterward try drawing some simple flowers : a snowdrop in a small vase ; a crocus—bulb, stem, and flower ; a daffodil with a few broad spear-like leaves.

And if we find it difficult to interpret shapes with our pencil, and our brain tires, and our fingers get weary, choose some very different and opposite' shapes.

The mere task of choosing requires a little stimulating reflection.

For instance, contrast a flat, squat-shaped, circular inkpot with a small, narrow upright tumbler ; a big spoon w.th a broad- handled knife. Compare a lemon with a tangerine ; an egg with an apple ; a reel of cotton with a tube of water-colour paint ; a matchbox with an ash-tray ; a tall slender vase and a dumpy bowl ; a large breakfast-cup and a small cocoa-tin ; a flat, thin book and a sphere-shaped paper-weight.

Put some of these objects on a table, at a little distance from your desk, and sketch them two by two, and side by side. You could draw some with your pencil, and some with your brush.

The lemon and the tangerine are excellent subjects for this test, because you have contrast of both shape and colour.

If you sketch them first with your brush, choose a tint of which they are both composed—say, a very pale yellow.

Draw first the lemon, the large, elongated, egg-shaped variety. Notice the characteristic knob, like a nose, at one end, and compare this with the round tangerine and its somewhat flattened top. You will find a further interest in comparing colours. How rich is the orange tinge beside the paler yellow ! How deep the shadows of the tangerine appear when compared with those of the lighter-hued lemon ! For the lemon we must seek out our cool blues and pale golds ; for the tangerine, warm crimson, and even touches of bronze and brown.

If we wish to handle our pencils intelligently (to get from our pencil many varied touches), we should draw objects which are variously composed. In other words, made of more than one material. And here again we must don our thinking-cap.

We need not go very far. A few homely domestic articles would furnish us with some useful models.

Take a feather brush—that is, a brush composed of feathers, leather, and smooth polished wood ; hang this up at a level with your eye, feathers downward, and sketch it with your pencil.

Draw a long line to represent the handle, and indicate the rough fan-shape of the lower part. If the handle is grooved and turned, do not worry because you cannot get both sides exactly alike. First sketch the largest shapes and remember to keep the stick slender ; next the three-cornered piece of leather which neatly hides and binds the ends of the feathers together ; lastly, the feathers themselves, spreading out in a loose, plumy fan.

Having sketched these shapes, darken the handle, which is polished and black. Leave the white paper to show through to provide the lights. Try to represent the polish of the surface by drawing with firm sharp touches.

The leather, being of a more pliable material and of a duller surface, needs a lighter treatment. If it has a dull tint, give it a shaded tone ; if it has folds, draw these folds in shadow.

Next the feathers.

A feather is one of the lightest of all substances. We say " light as a feather " when we wish to suggest something of the airiest description.

But although it is so unsubstantial, it is not feeble. It has a definite shape.

Each feather has a spine from which it spreads in a definite shape. Soft, yes, and delicate, but with a curved spine and a broad tip. Look at those nearest to you . . . and draw their shapes delicately. Hold your pencil lightly, give a gentle, feathery touch, and, as the feathers are bunched together, and some will be in shadow, put in the shadows lightly, but sharply. Then pause and look at your drawing.

Have you ' handled ' the drawing of the wood and the feathers differently ? Does the leather look more substantial than the feathers ?

The work is not easy, but practice will soon give a surer touch. You are playing a scale with your pencil as one plays a scale on a piano. Deep bass notes, then the middle 'strong notes, and lastly the soft delicate treble. We must try to make our pencil speak with a varied tongue.

Drawing different textures might include a kettle and a kettle-holder (shiny metal—rough cloth or velvet) ; a small piece of fur coiled near, or over, a hard cricket-ball ; a cake of soap and a loofah. A woman's hat with a soft wide brim (not the pudding basin variety, which is most difficult for unpractised fingers), trimmed with a cluster of berries, or a twisted bow of ribbon, gives us several different textures.

We must hold the pencil delicately, loosely, and half-way up the shaft if we wish to convey the delicacy of fur and fine hairs. If we would show the richness of velvet, we must use our pencil with determination and shift our fingers for a shorter and firmer grip.

All this will come with practice. There is no need to worry yourself with harassing doubts. Do your best ; no one can do more.When we work alone, we are very apt to get weary and depressed with our difficulties.

We sit before our little models and look so often that we see less and less, instead of more and more.

It is very wise occasionally to cover up your model, or, at any rate, to turn your back upon it for a while.

This will often appear to increase your difficulties, but A toy tree might well bring up the rear of our procession. And a toy tree is a very simple affair, a thimble-shape on the end of stick, very like a large T with elongated lines drooping on either side.

Looking at the tree as a whole mass we see that the branches extend more than half-way down the stem. Lightly we sketch the line of these branches. Then we look at the trunk of the tree. It is thick and solid for its height. Then thick and solid we will draw it. Next we come to its little green stand, like a slice of the one which supports Mr Noah, and this stand is smaller than the circumference of the tree at the widest part.

Baby Tom's unbreakable Bunny is surely the simplest of all shapes—a flat base from which rises a rounded hill, steeper on one side than on the other. The steeper, more massive end corresponds with the crouching hind-legs (which we know to be the largest part of the rabbit and which help him to run so fleetly across the warren).

From the top of the head the ears lie flat along the body. Then we mark the small eye, the rounded soft nose, and the tiny forepaws. We look for folds of leg, paw, and ear, and we shade these with a light but firm touch. Bunny Rabbit is white and therefore must not be shaded too strongly. And if you wish to insist on his white coat, look for shadows cast by his rounded body on the ground or background.

The fish of painted celluloid is interesting and by no means difficult to draw, although at first glance we may be slightly puzzled where and how to begin.

A fish is long—one almost might term it domino-shape. Begin, then, as always, by sketching out this general shape.

This done, we trace from the wider and larger end of the fish the long sloping line to the branching tail. The forepart slopes steeply down from the ' shoulders ' and finishes with a rounded blunt nose. Next we notice that our fish—unlike a real fish—has a flattened underside upon which he rests on flat surfaces—and this we draw.

After this we proceed to sketch the gills, the curious breathing-apparatus of the fish, placed on either side of his head and behind his cheek.

Then we note the eye—circular in shape (not oblong like a human eye)—and the queer scoop of a mouth with the lower jaw jutting forward. We then sketch the tail, which is forked.

If we feel so disposed we can sketch a few of the fish's scales ; they overlap, beginning at the head and diminishing in size with the diminishing size of the tail-end of the body, We may also build up a picture with a group of several fishes drawn from the single model.

Turn the fish round, so that the head comes nearest. This will not be so easy to draw, because here we are confronted with something that is not on a flat plane. But do not let this worry you. When we are sketching something ' coming toward us ' we draw first the part that is nearest, then the parts behind.

If you draw two or three or even four fishes you might add a swirl of water, and some reeds. Then you will have completed a little picture.

Observe real ponds and reeds at your next opportunity, and if a fish darts before your eyes you will see that his fins and tail agitate the water.

By observing and remembering—we cannot always have a pencil in our hand—we build up pictures in our minds. Teddy Bear might next pose as a model.

He has a rounded head and a pointed snout. These we sketch very roughly—something like the shape of a pear.

He has a round, fat, pillow-shaped body, to which are attached his fat little thighs, the backward-sloping hind-legs, and his small but solid feet thrust sturdily forward. To the top of his head we must add his large, soft, round ears. The front part of his forehead curves in a decided kink, and his queer little snout soars upward. His nose is black and shiny, and the noses of bears are three-corner shape, wide at the top, curling round the nostrils and narrowing to the upper lip. The lower jaw of Teddy Bear is small and retreating, and his mouth curves upward in a pleased little smile.

His upper arms are very thick, and they scoop downward and outward and end in rounded paws. Teddy Bear might carry our study further. In all probability he will wear a coat or tunic. Then draw the little garment carefully. Draw the folds under the arms, and the belt round the waist, and the pattern about the edge of it.

Teddy Bear is different from the wooden creatures of the ark or the velveteen of Bunny Rabbit. He has a furry coat.

Try to indicate with several strokes of the pencil the furry shadows in his ears, behind his cars, in the bend of his arms and legs, and the shaggy little fringe of his paws and hind-legs.

Draw the furry lines lightly. His coat is of a soft substance. Draw some of the thick curls with their queer little twists, and the shadows on the curve of the ragged edges.

His eye is dark and bright. It has a shiny light, being of a shiny substance. Draw the dark shadow of the little eye with strong, dark touches, leaving the light untouched.

There, you see, we have the fur of the coat, the velvet of the dress, and the button of an eye. Three different substances requiring different handling of the pencil.

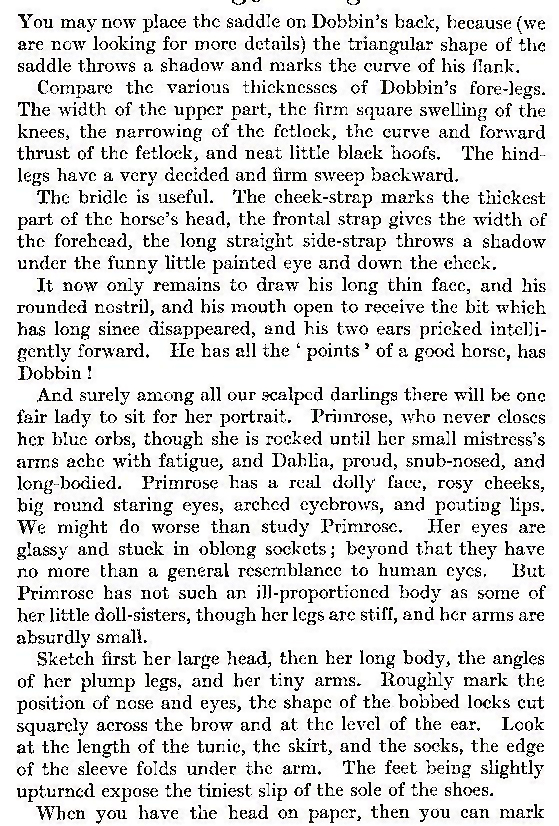

Dobbin, who has carried us so many miles round the nursery-floor that all his tail and most of his mane has sprinkled the highway of our fancy, Dobbin, after all is said and done, is a horse. He has four legs, a stout body, an arched neck, and a spirited eye and nostril.

See how smooth and round is his body, and how firmly the four legs are fastened to the corners, and how squarely the neck is placed ! His hoofs are stoutly fixed on the ground, the left fore-leg and the right hind-leg stepping forward. First note the barrel shape of his body and draw that firmly, placing the legs at each corner and simply marking the angle from the top of the leg to the hoof. Then place the curved neck on the square shoulders and trace the long face. (The horse-faced individual,' a rude nickname we sometimes hear, suggests a man or woman with a very long face.)

You may now place the saddle on Dobbin's back, because (we are now looking for more details) the triangular shape of the saddle throws a shadow and marks the curve of his flank.

Compare the various thicknesses of Dobbin's fore-legs. The width of the upper part, the firm square swelling of the knees, the narrowing of the fetlock, the curve and forward thrust of the fetlock, and neat little black hoofs. The hind-legs have a very decided and firm sweep backward.

The bridle is useful. The cheek-strap marks the thickest part of the horse's head, the frontal strap gives the width of the forehead, the long straight side-strap throws a shadow under the funny little painted eye and down the cheek.

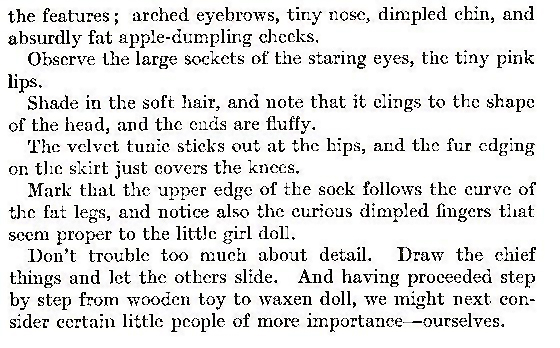

It now only remains to draw his long thin face, and his rounded nostril, and his mouth open to receive the bit which has long since disappeared, and his two ears pricked intelligently forward. He has all the ' points' of a good horse, has Dobbin ! And surely among all our scalped darlings there will be one fair lady to sit for her portrait. Primrose, who never closes her blue orbs, though she is rocked until her small mistress's arms ache with fatigue, and Dahlia, proud, snub-nosed, and long- bodied. Primrose has a real dolly face, rosy cheeks, big round staring eyes, arched eyebrows, and pouting lips. We might do worse than study Primrose. Her eyes are glassy and stuck in oblong sockets ; beyond that they have no more than a general resemblance to human eyes. But Primrose has not such an ill-proportioned body as some of her little doll-sisters, though her legs are stiff, and her arms are absurdly small.

Sketch first her large head, then her long body, the angles of her plump legs, and her tiny arms. Roughly mark the position of nose and eyes, the shape of the bobbed locks cut squarely across the brow and at the level of the ear. Look at the length of the tunic, the skirt, and the socks, the edge of the sleeve folds under the arm. The feet being slightly upturned expose the tiniest slip of the sole of the shoes.

When you have the head on paper, then you can mark the features ; arched eyebrows, tiny nose, dimpled chin, and absurdly fat apple-dumpling cheeks.

Observe the large sockets of the staring eyes, the tiny pink lips.

Shade in the soft hair, and note that it clings to the shape of the head, and the ends are fluffy.

The velvet tunic sticks out at the hips, and the fur edging on the skirt just covers the knees.

Mark that the upper edge of the sock follows the curve of the fat legs, and notice also the curious dimpled fingers that seem proper to the little girl doll.

Don't trouble too much about detail. Draw the chief things and let the others slide. And having proceeded step by step from wooden toy to waxen doll, we might next consider certain little people of more importance—ourselves.

Privacy Policy .... Contact Us