DECORATIVE DESIGN AND DRAWING

DECORATIVE DESIGN

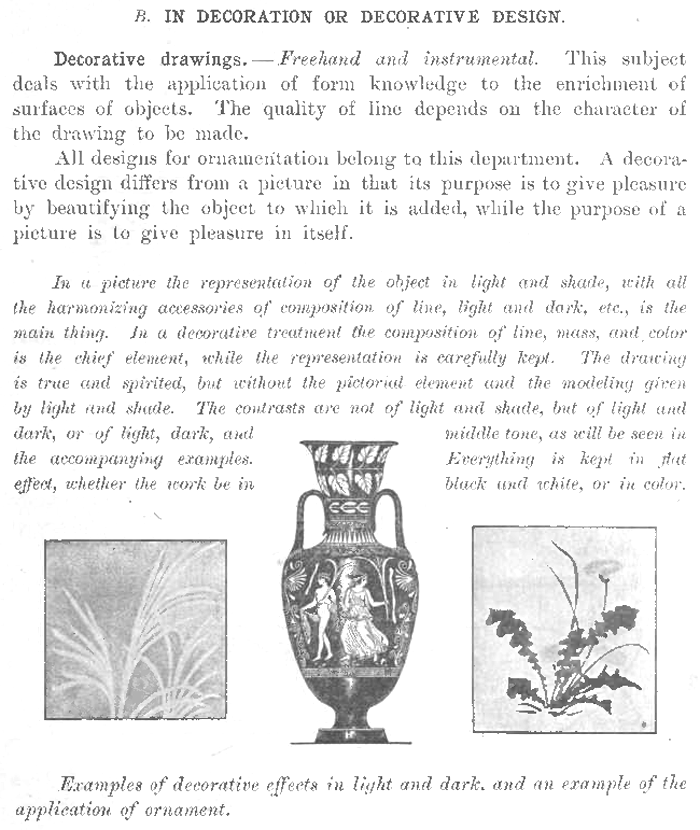

Decorative drawings. —Freehand and instrumental. This subject deals with the application of form knowledge to the enrichment of surfaces of objects. The quality of line depends on the character of the drawing to be made.

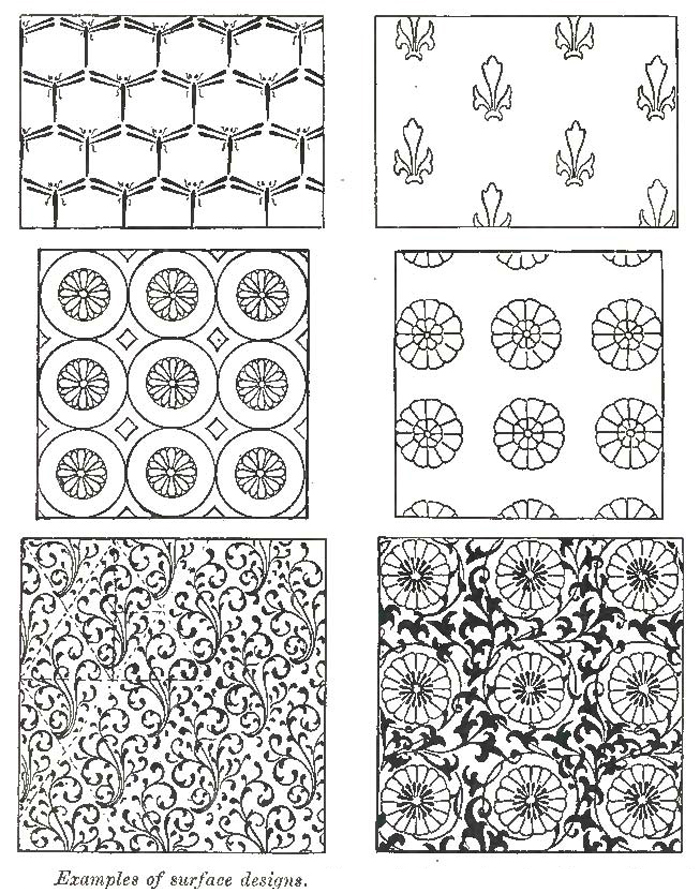

All designs for ornamentation belong to this department. A decorative design differs from a picture in that its purpose is to give pleasure by beautifying the object to which it is added, while the purpose of a picture is to give pleasure in itself.

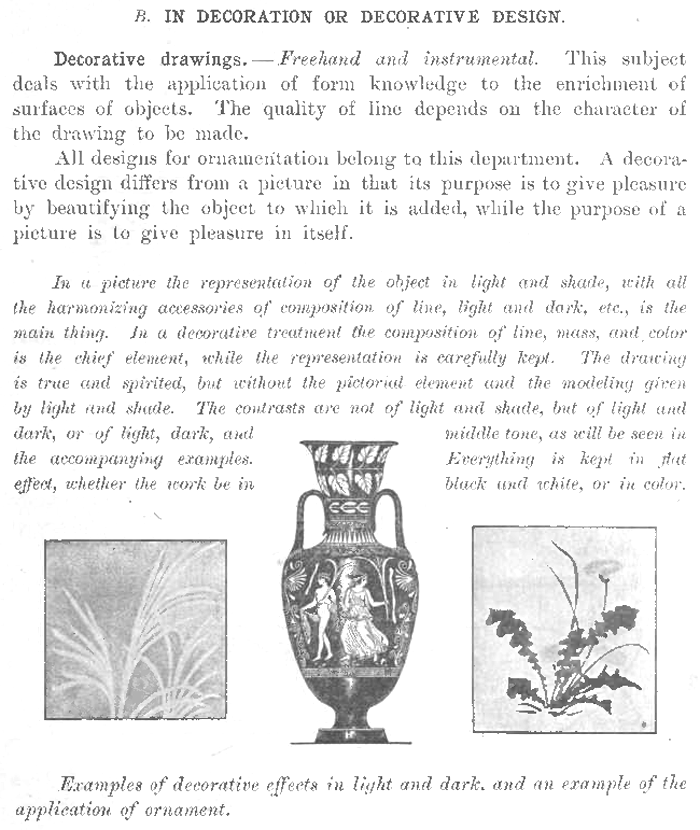

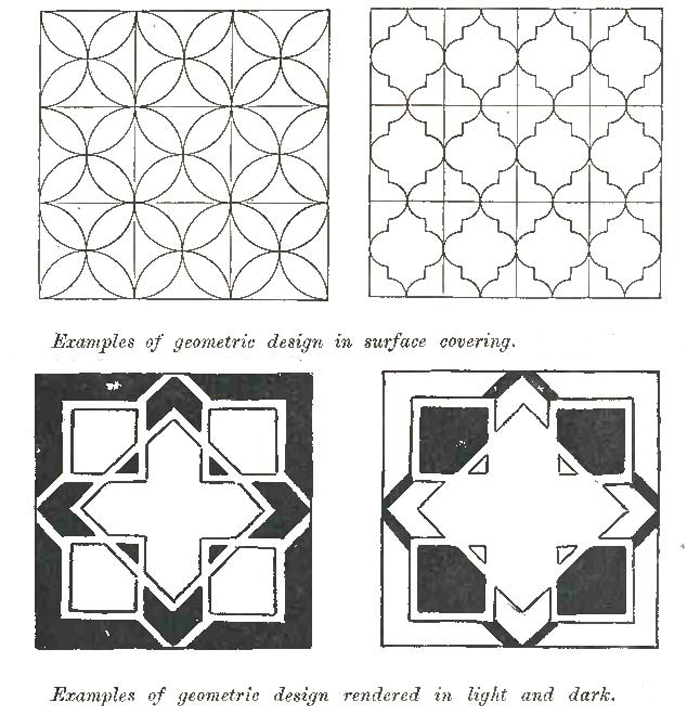

In a picture the representation of the object in light and shade, with all the harmonizing accessories of composition of line, light and dark, etc., is the main thing. In a decorative treatment the composition of line, mass, and color is the chief element, while the representation is carefully kept. The drawing is true and spirited, but without the pictorial element and the modeling given by light and shade. The contrasts are not of light and shade, but of light and dark, or of light, dark, and the accompanying examples.

Examples of decorative effects in light and dark, and an example of the application of ornament. Front The

Mechanical aids, such as rule, compasses, tracing and transferring, may be employed in decorative drawing. Tracing paper may be used, or the unit may be cut out and repeated by tracing with a sharp pencil.

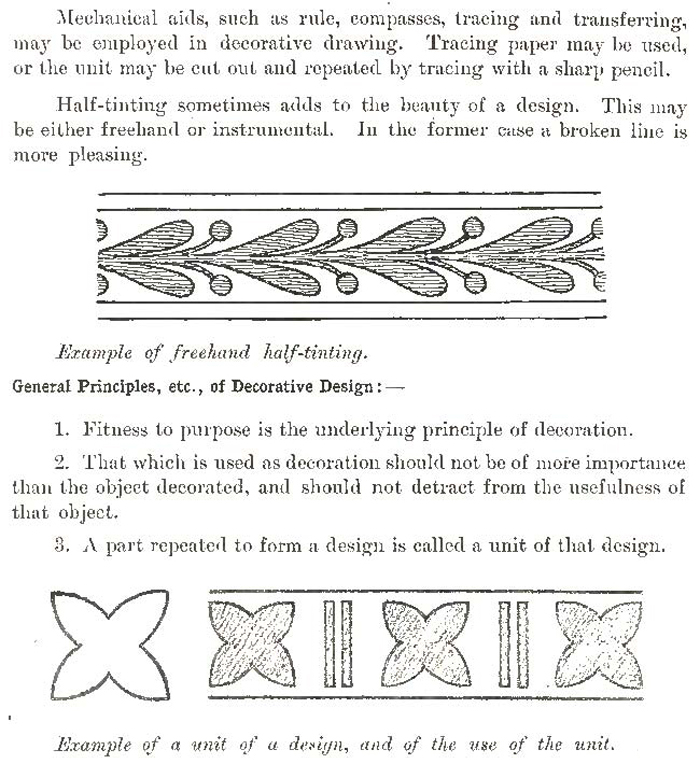

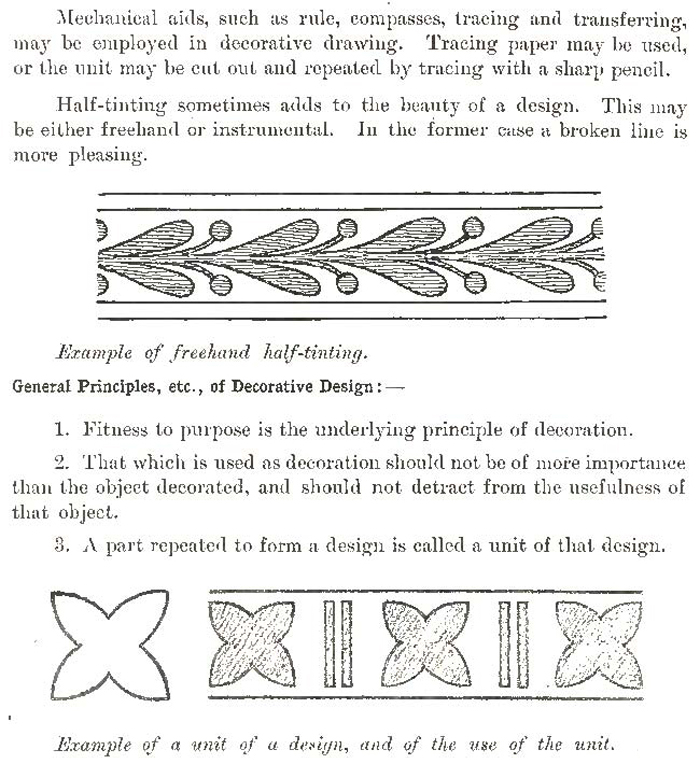

Half-tinting sometimes adds to the beauty of a design. This may be either freehand or instrumental. In the former case a broken line is more pleasing.

1. Fitness to purpose is the underlying principle of decoration.

2. That which is used as decoration should not be of more importance than the object decorated, and should not detract from the usefulness of that object.

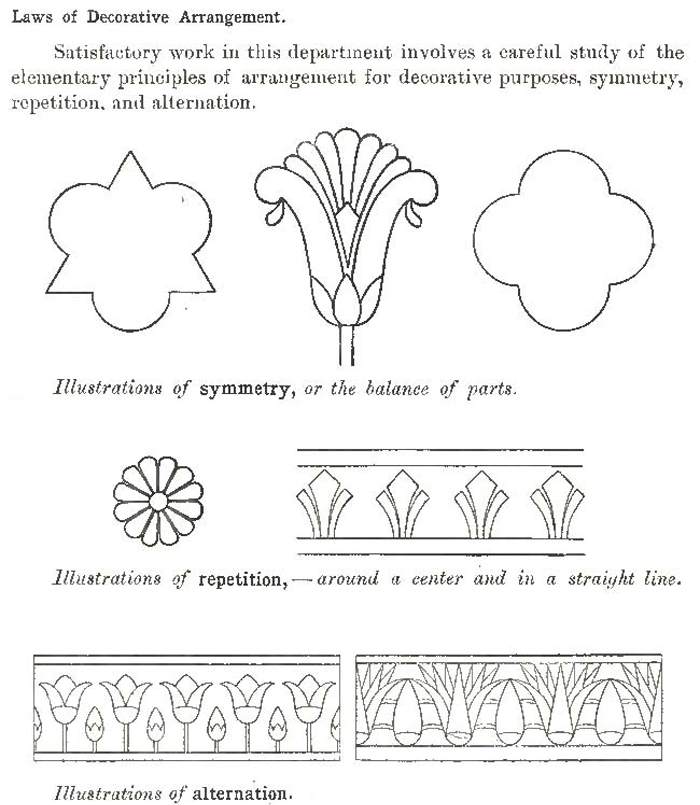

3. A part repeated to form a design is called a unit of that design.

Example of a unit of a design, and of the use of the unit. From The Prang Elementary Course in Art Instruction, Book 1.

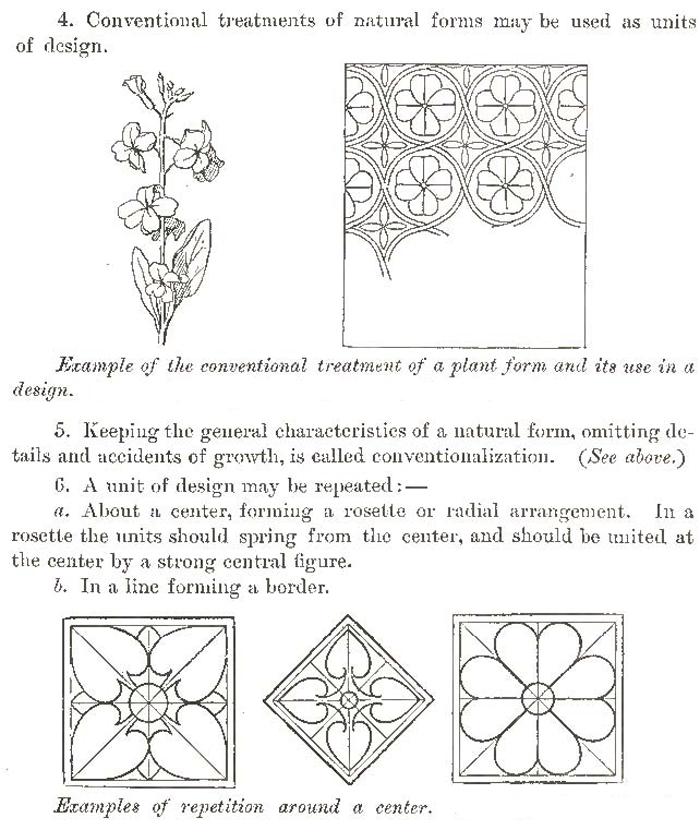

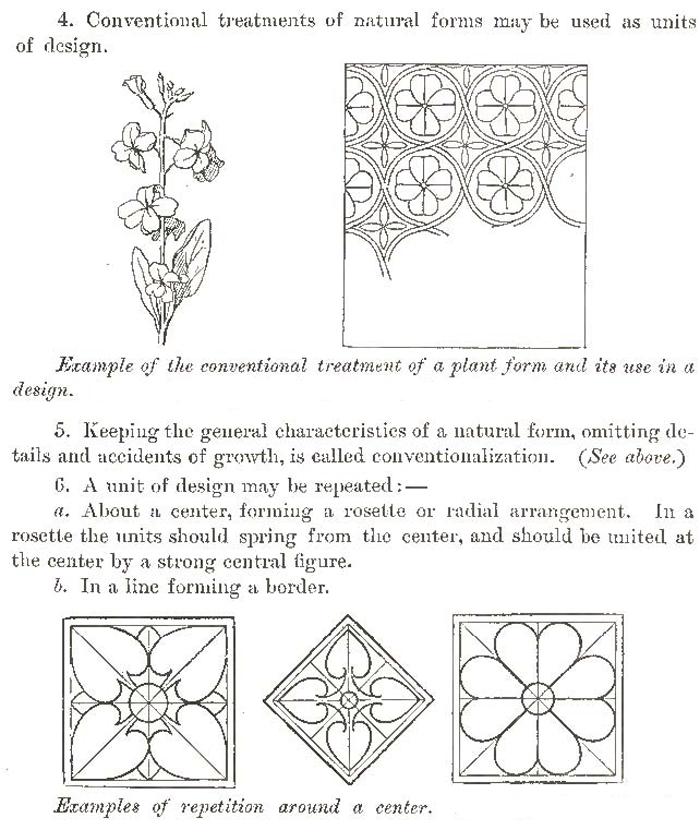

4. Conventional treatments of natural forms may be used as units of design.

Example of the conventional treatment of a plant form and its use in a design. From The Prang Complete Course, Manual Part M.

5. Keeping the general characteristics of a natural form, omitting details and accidents of growth, is called conventionalization. (See above.)

6. A unit of design may be repeated :—

a. About a center, forming a rosette or radial arrangement. In a rosette the units should spring from the center, and should be united at the center by a strong central figure.

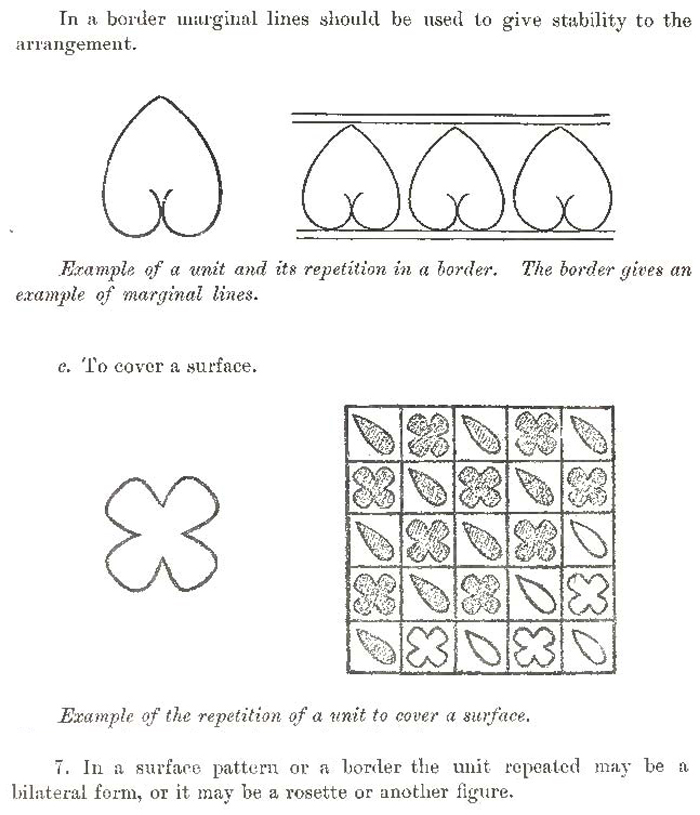

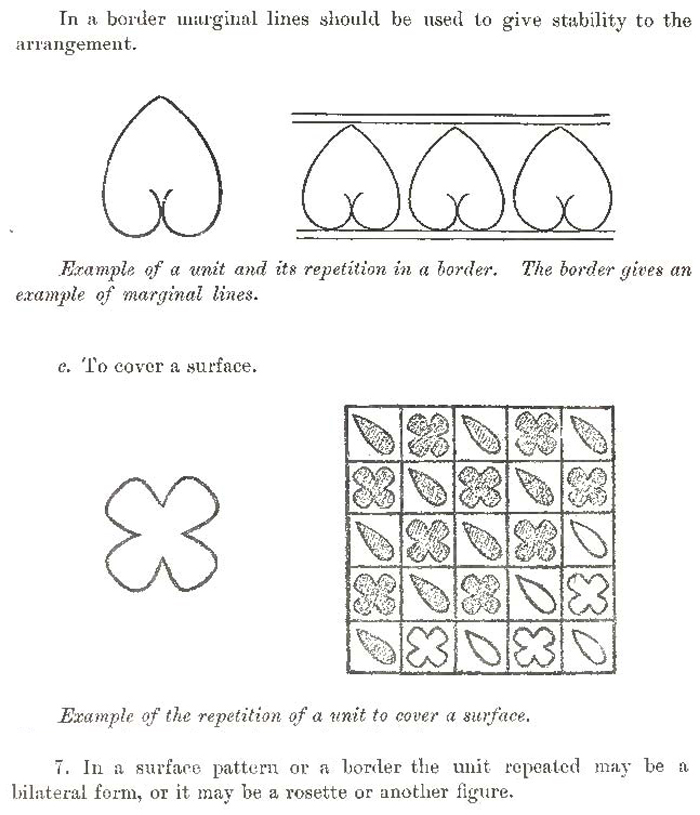

b. In a line forming a border.

c. To cover a surface.

7. In a surface pattern or a border the unit repeated may be a bilateral form, or it may be a rosette or another figure.

8. A bilateral form is one having an axis of symmetry ; that is, one which may be divided into two parts that balance.

The sources of materials for decoration are geometric figures and natural forms. " All noble ornamentation is the expression of man's delight in God's work."

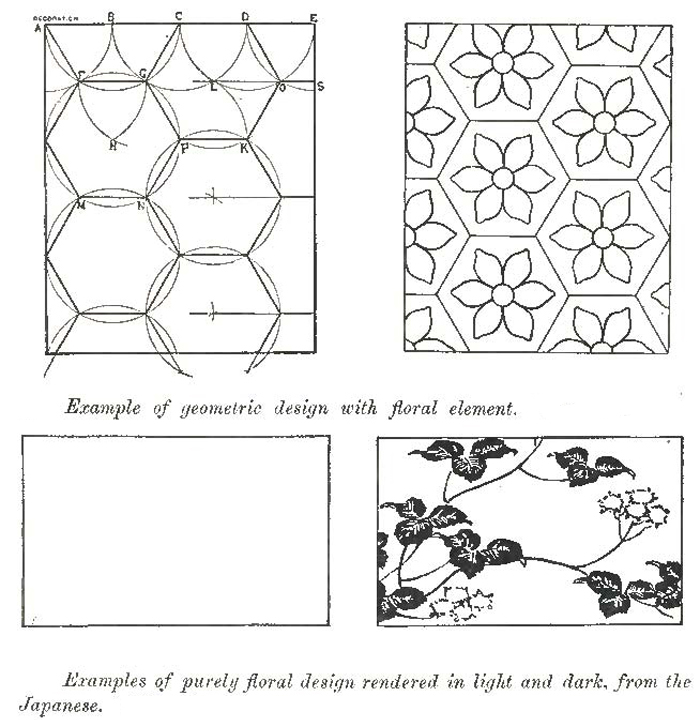

Any geometric figure may be used in decoration, simple or modified, to meet necessary conditions. In original design requiring the use of plant forms, care should be taken to observe the law of growth.

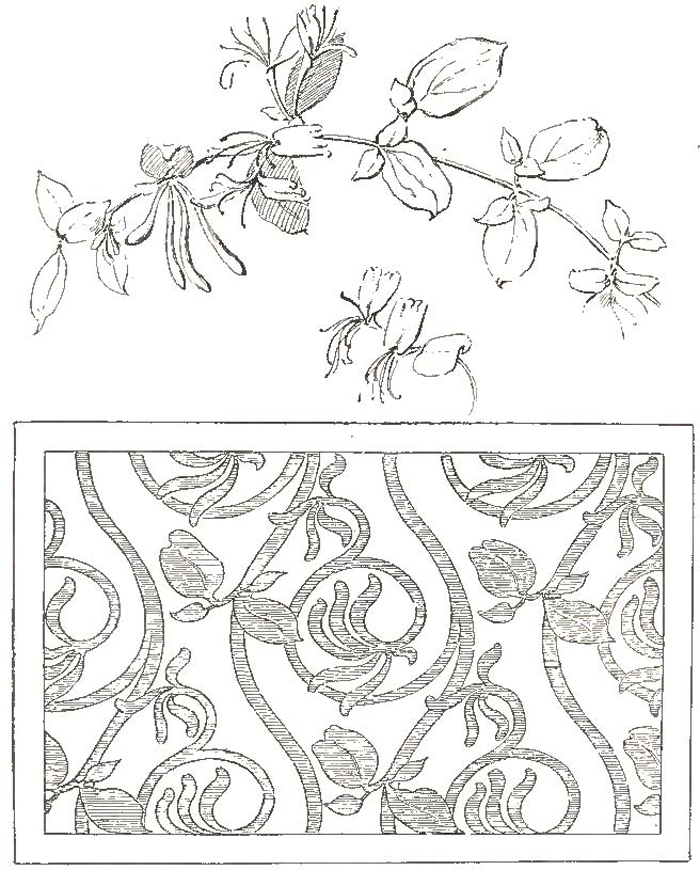

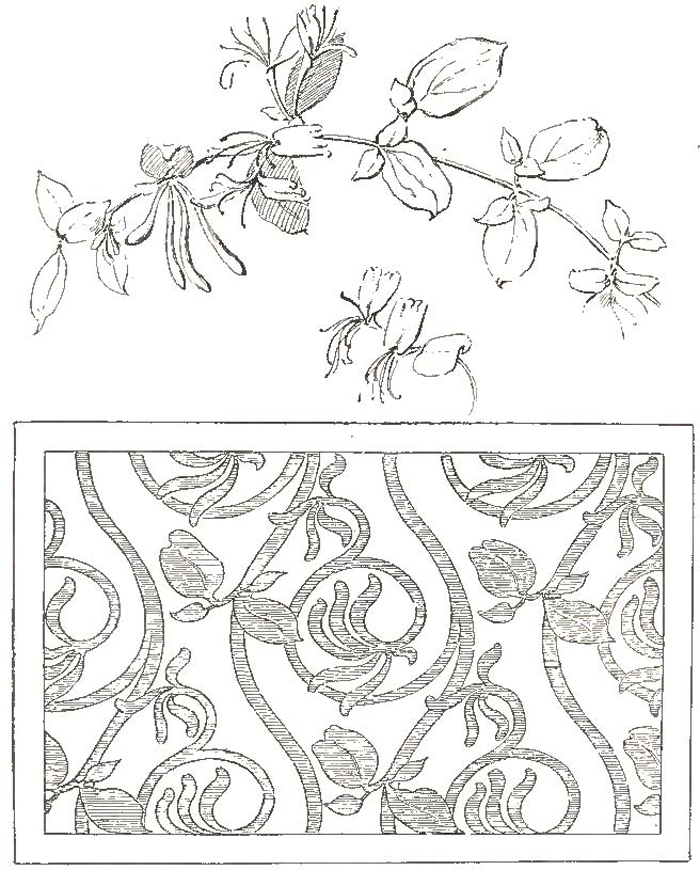

Example of the nose of leading lines, suited to "laws of growth," as a preliminary step in a design.

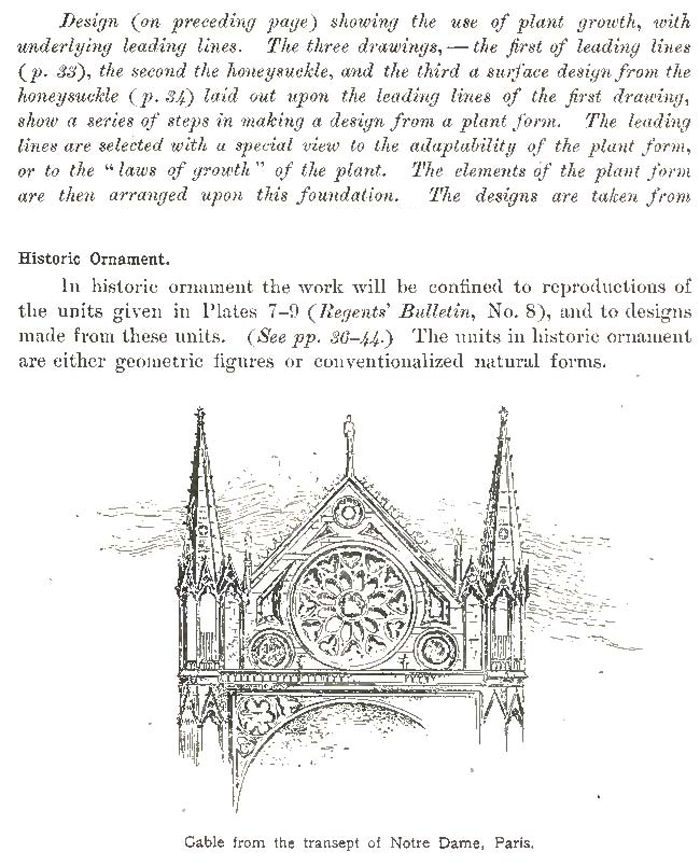

Design (on preceding page) showing the use of plant growth, with underlying leading lines. The three drawings, — the first of leading lines, the second the honeysuckle, and the third a surface design from the honeysuckle laid out upon the leading lines of the first drawing, show a series of steps in making a design from a plant form. The leading lines are selected with a special view to the adaptability of the plant form, or to the "laws of growth" of the plant. The elements of the plant form are then arranged upon this foundation.

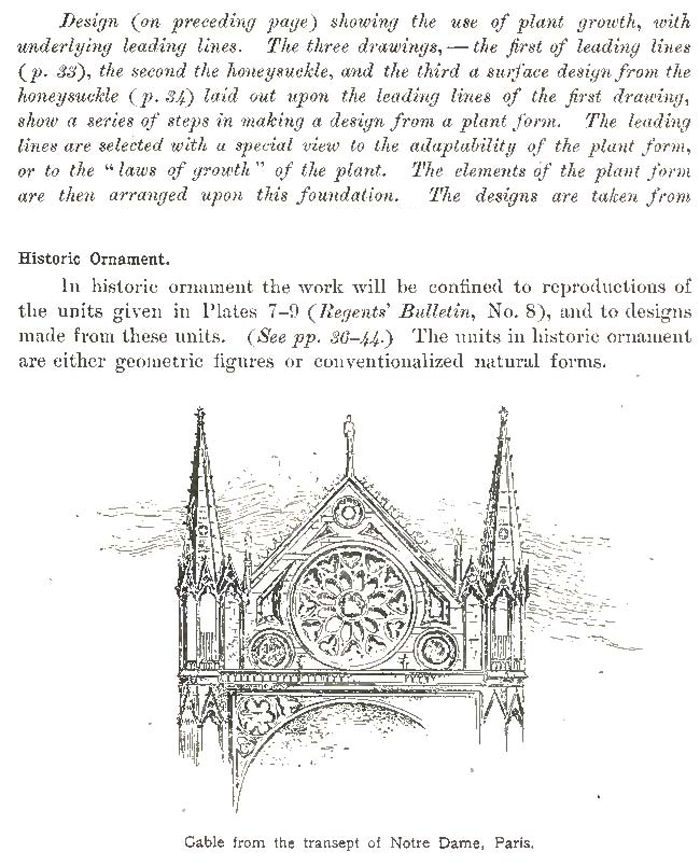

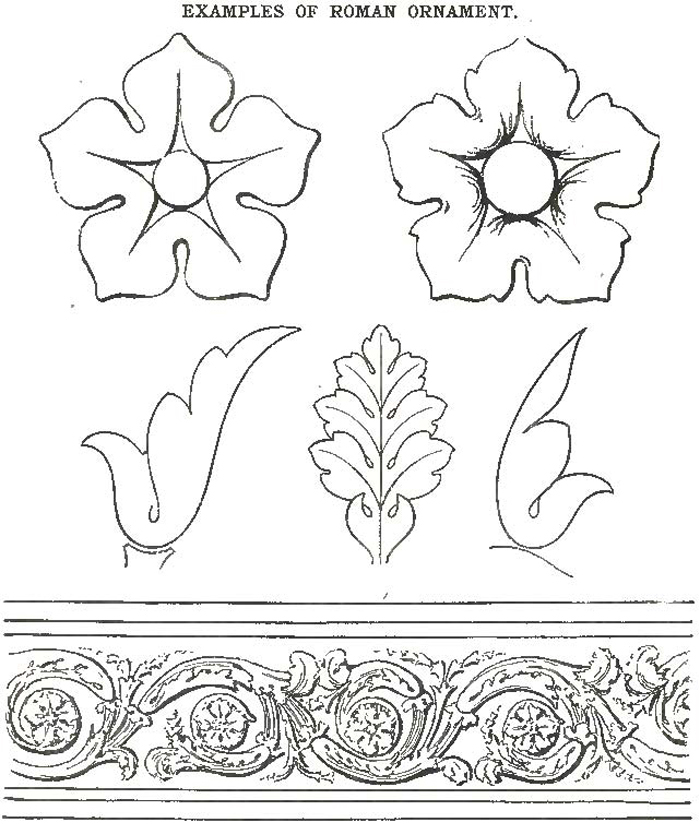

In historic ornament the work will be confined to reproductions of the units given in Plates 7-9 (Regents' Bulletin, No. 8), and to designs made from these units. The units in historic ornament are either geometric figures or conventionalized natural forms.

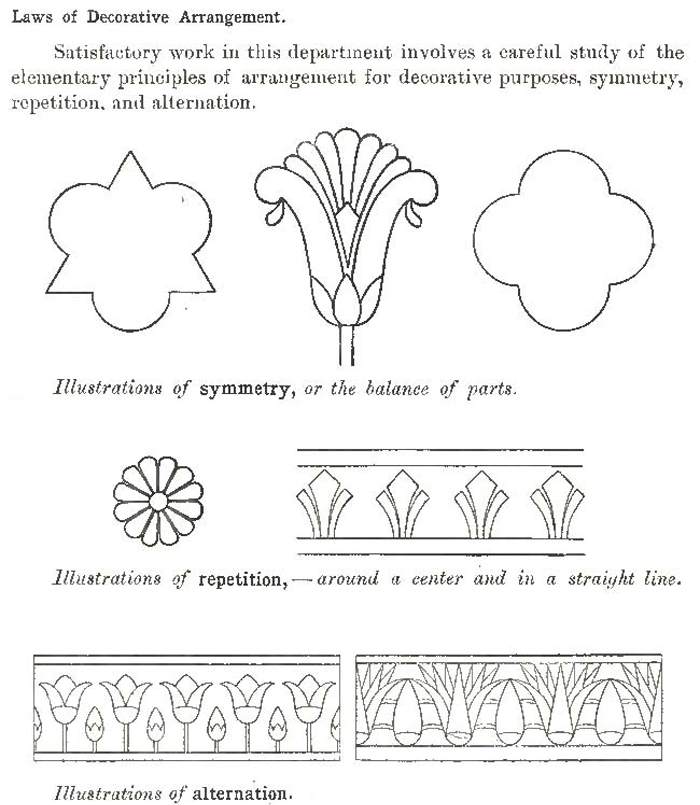

Satisfactory work in this department involves a careful study of the elementary principles of arrangement for decorative purposes, symmetry, repetition, and alternation.

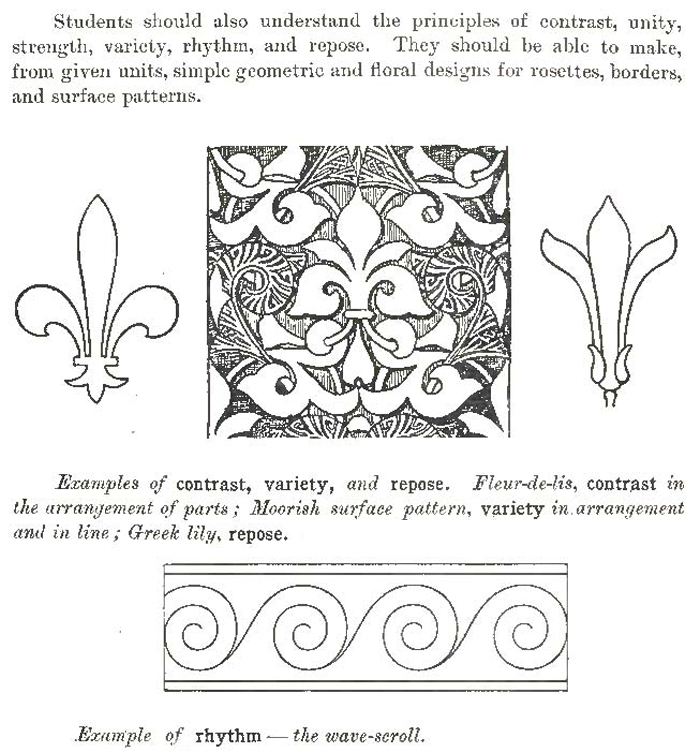

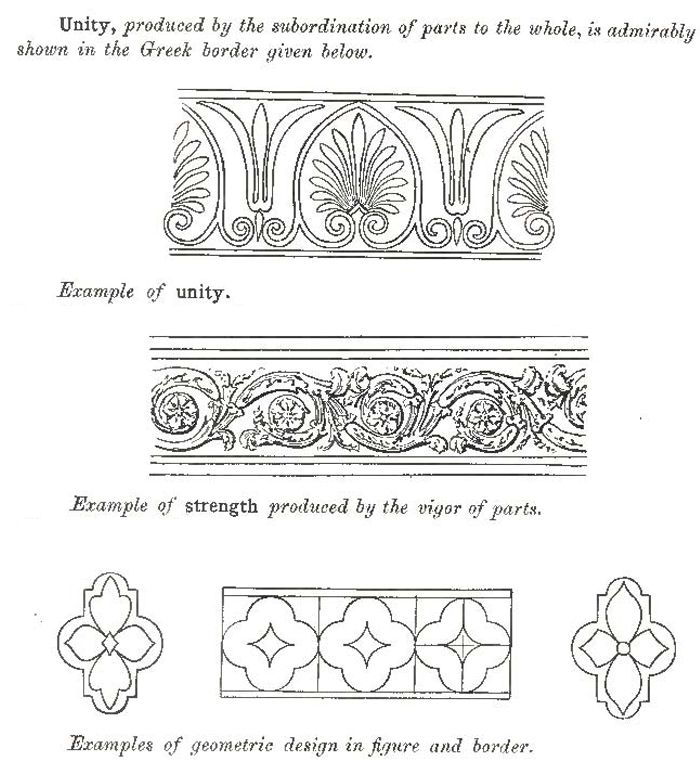

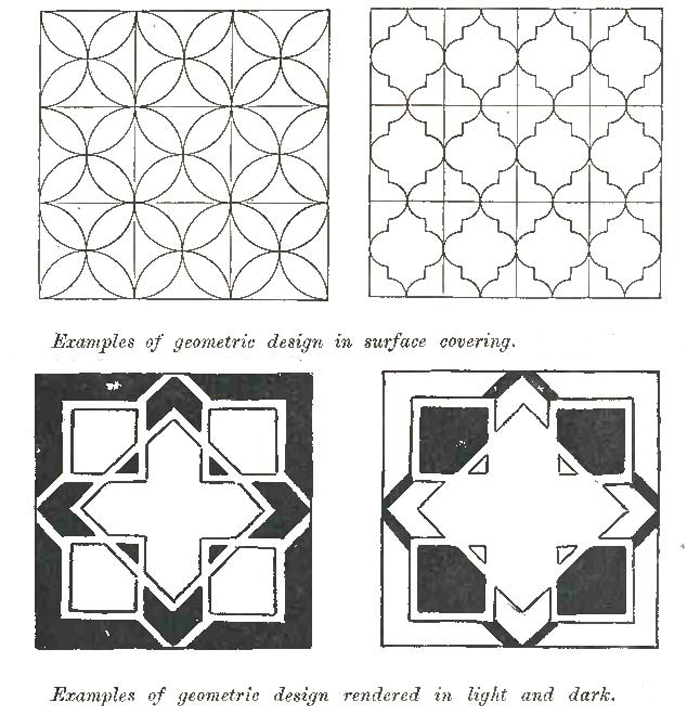

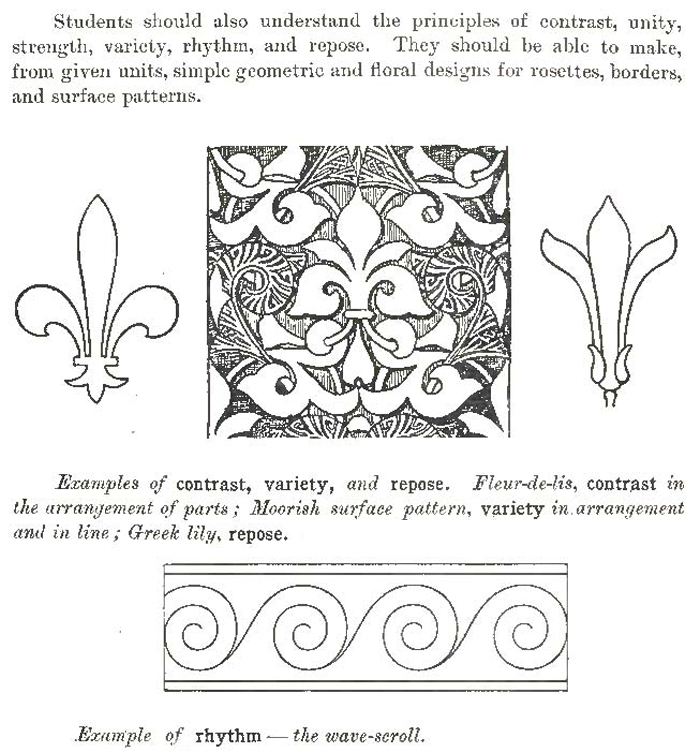

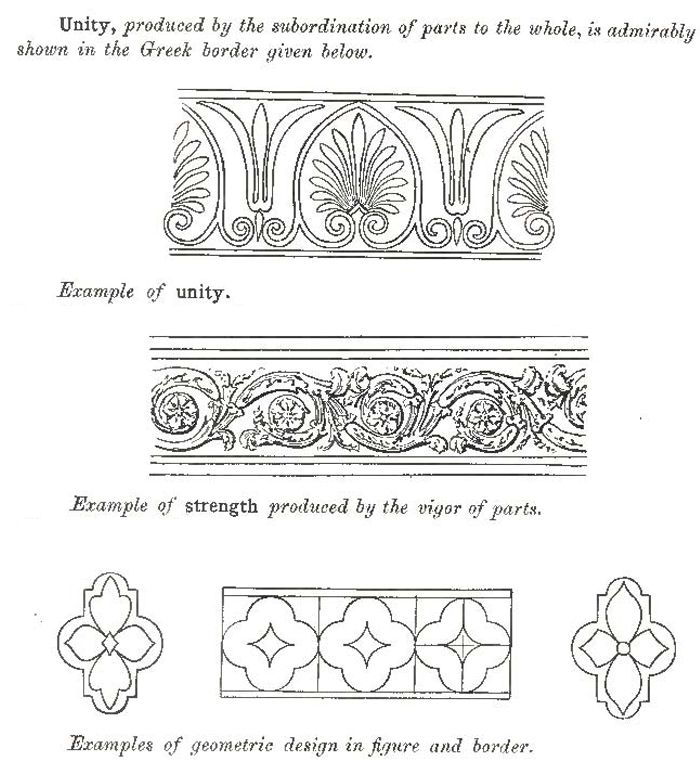

Students should also understand the principles of contrast, unity, strength, variety, rhythm, and repose. They should be able to make, from given units, simple geometric and floral designs for rosettes, borders, and surface patterns.

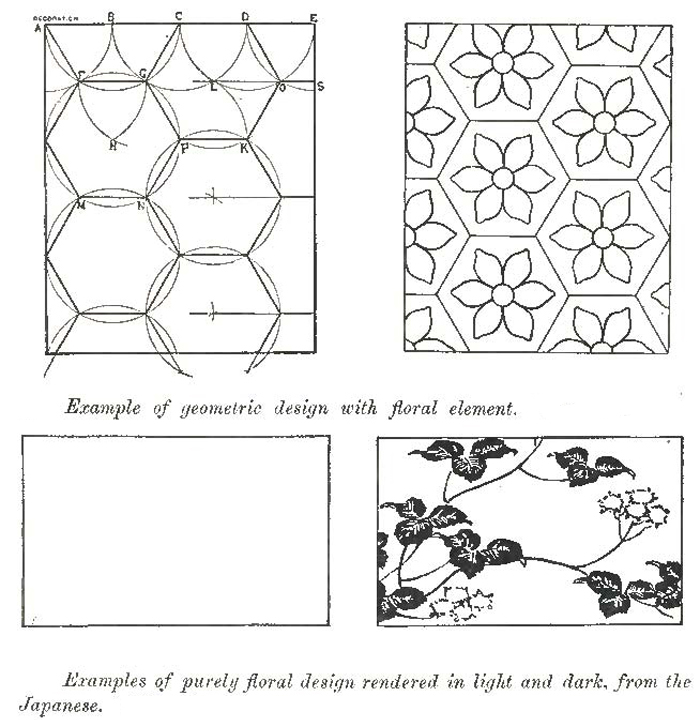

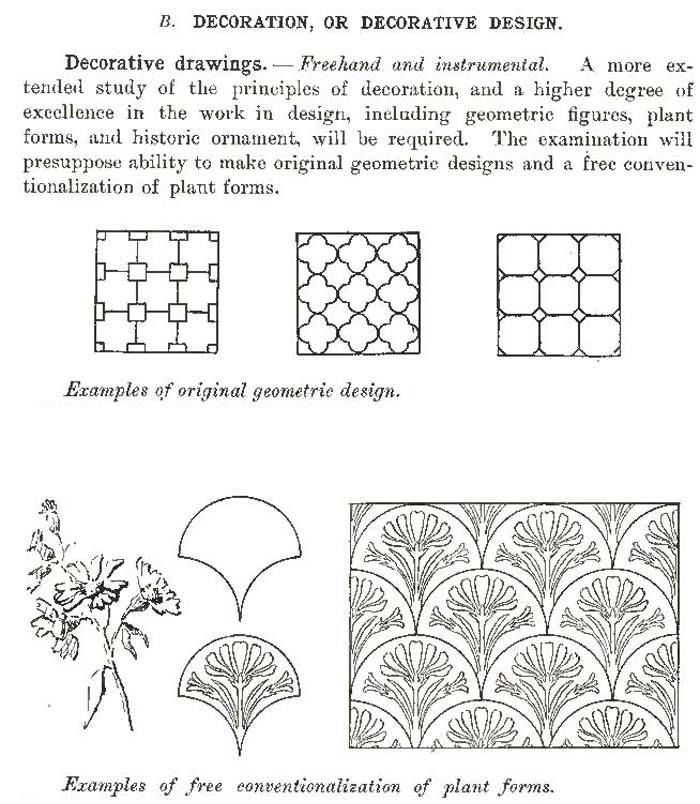

Decorative drawings. — Freehand and instrumental. A more extended study of the principles of decoration, and a higher degree of excellence in the work in design, including geometric figures, plant forms, and historic ornament, will be required. The examination will presuppose ability to make original geometric designs and a free conventionalization of plant forms.

It will include bilateral arrangements with or without inclosing forms and conventionalized plant forms.

Examples of bilateral arrangements— with an inclosing form in the surface design, without the inclosing form in the single units.

The student of decoration should become familiar with the leading styles of ornament of nations of the past. To aid in this study a few thoughts suggested by R. N. Wornum in his Analysis of Ornament are given below, followed by an abstract of the work itself.

Ancient. — Egyptian, Greek, Roman.

Mediaeval. —Byzantine, Saracenic, Gothic. Modern. — Renaissance.

Egyptian. — Symbolism, simplicity, grandeur, severity, conventionalization of natural forms.

Greek. — Estheticism, artistic finish, simplicity, conventionalization. Roman. — Estheticism, extreme elaboration, richness.

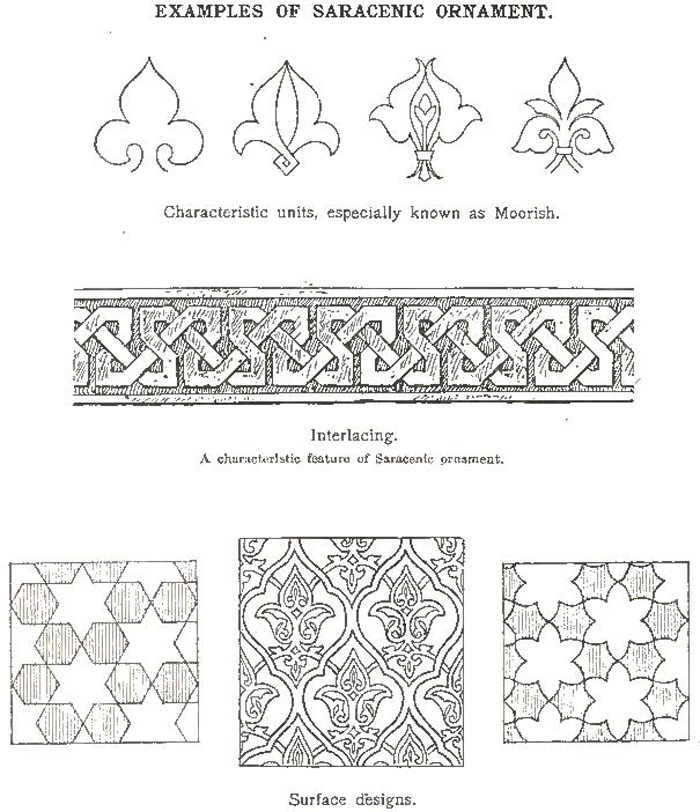

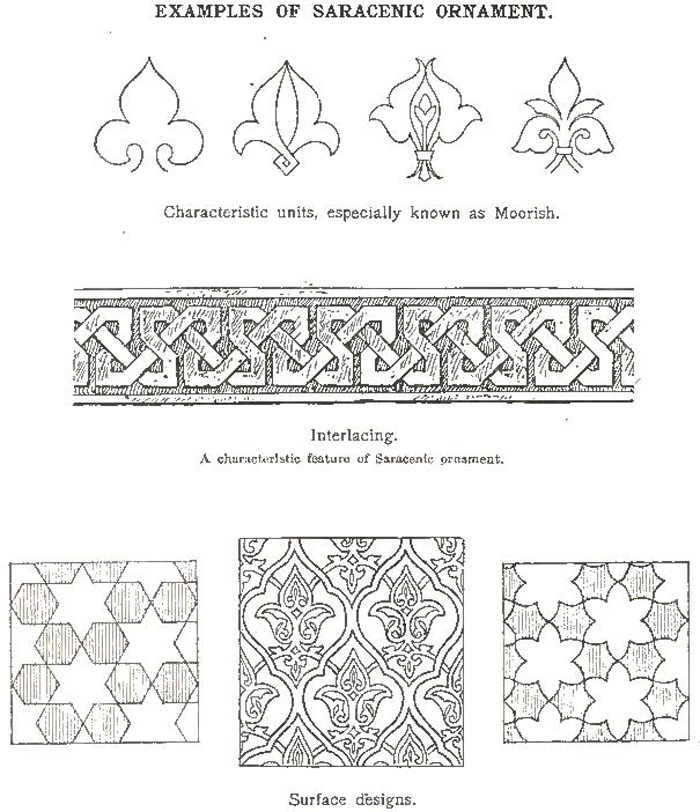

Byzantine. — Christian symbolism, estheticism, conventionalization. Saracenic or Moorish. — Rigid exclusion of symbolism, geometric symmetry, gorgeous color effects.

Gothic. — Christian symbolism, grandeur.

Renaissance, with its developments (trecento, cinquecento, Louis Quatorze). — Rebirth of classic styles, estheticism.

These various styles extended over a period of 3500 years, of which 2000 may be considered the ancient period, from the early historical times to the third century of our era. About 1000 years, from the third to the thirteenth century, may be .considered the medieval ; and the last five. centuries, the modern or renaissance period.

Style is another name for character. Every style depends on what is peculiar to it, never on what it has in common with other styles. These peculiarities are termed characteristics. The earliest styles are the most simple.

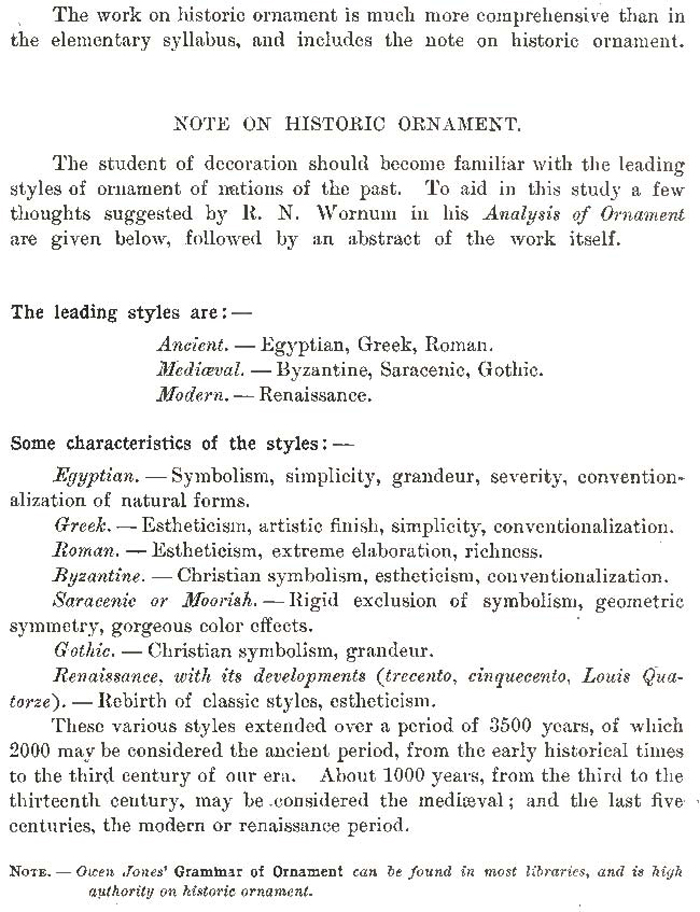

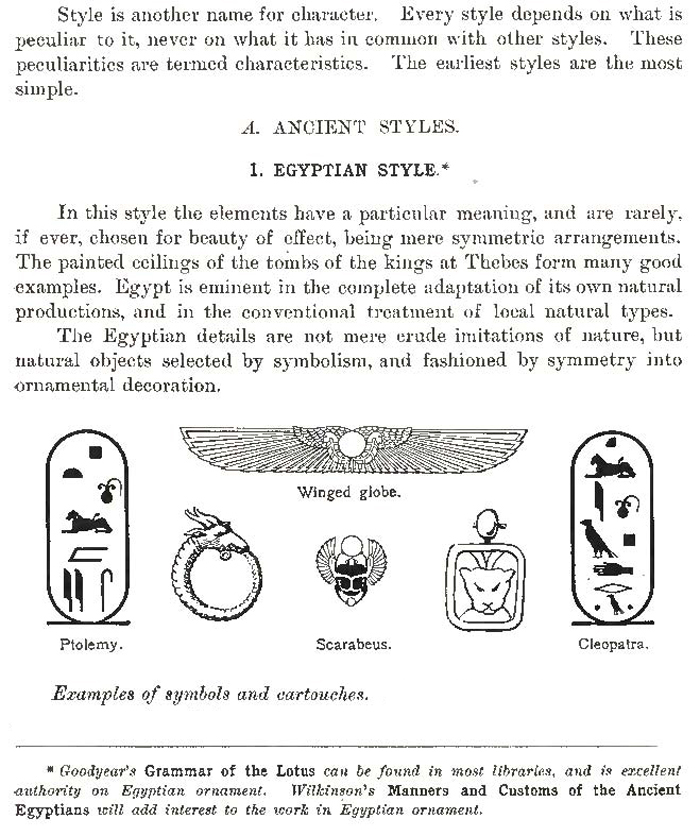

In this style the elements have a particular meaning, and are rarely, if ever, chosen for beauty of effect, being mere symmetric arrangements. The painted ceilings of the tombs of the kings at Thebes form many good examples. Egypt is eminent in the complete adaptation of its own natural productions, and in the conventional treatment of local natural types.

The Egyptian details are not mere crude imitations of nature, but natural objects selected by symbolism, and fashioned by symmetry into ornamental decoration.

The use of symbols in surface decorations.

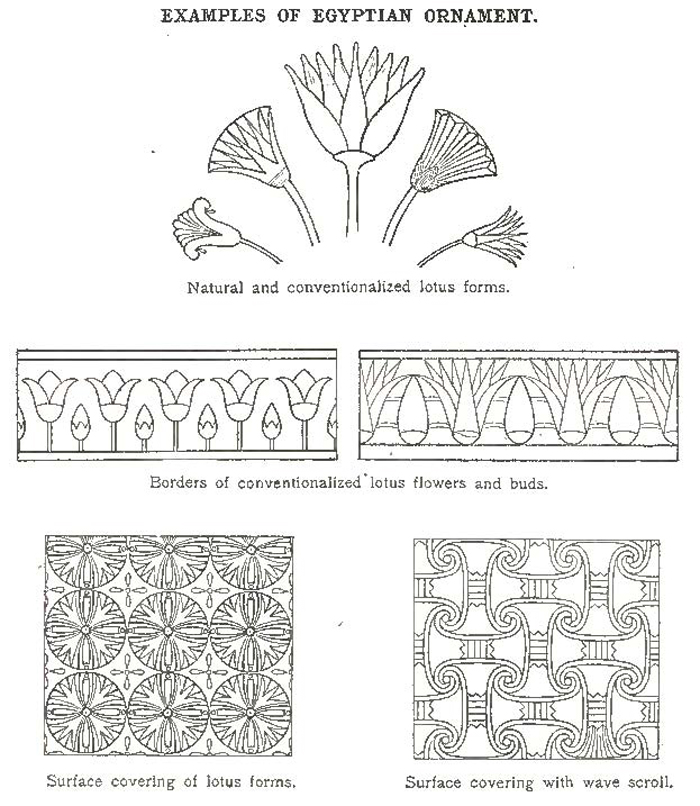

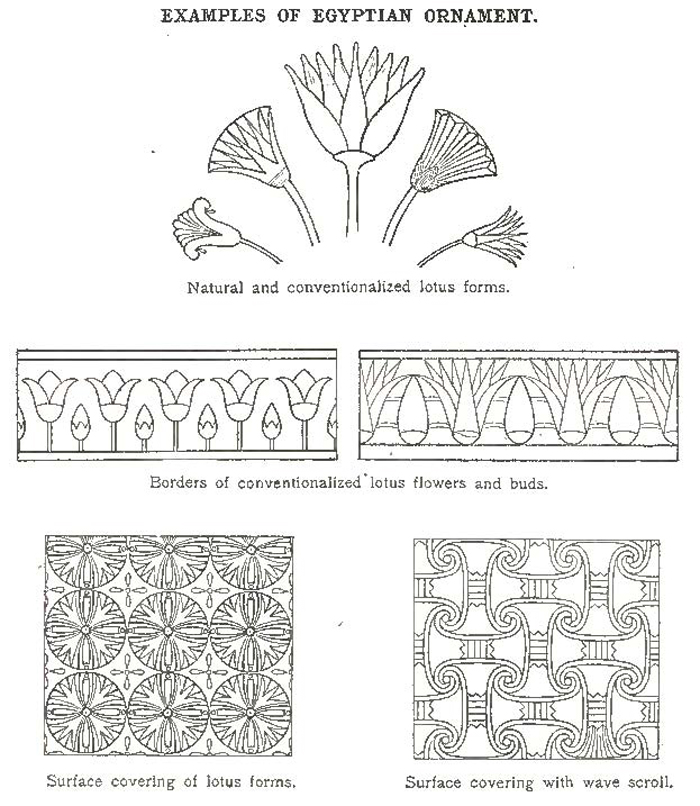

Examples of Egyptian borders and surfaces.

Here we have the earliest systematic efforts in design. In many respects the art was as thoroughly understood at Memphis or Thebes three thousand years ago, as it is at London or Paris to-day. Egyptian ornaments admit of no pictures of objects; all are treated conventionally.

Common Egyptian designs are : the winged globe, the beetle, the lotus, the papyrus, the zigzag, the asp, the cartouche, the spiral, the wave scroll, the fret, and the sphinx.

The beetle occurs in all sizes, and in almost all materials, and is a species of talisman or invocation of good luck.

The globe is supposed to represent the sun, the wings providence, and the two asps, one on each side of the globe, dominion and monarchy, or the creative, protective, and distributive powers, implying order.

We find this ornament placed over doors, windows, and in passages. it is sometimes of an enormous size extending thirty feet or more. It is also frequent in costumes and on mummy cases.

The Egyptian sphinx is a remarkable object in art. It is supposed to represent the combination of physical and intellectual power, or the kings as incarnation of such attributes. The chief position of the sphinx was on either side of the path leading to the temple.

The swelling asps we find arranged in symmetric opposition, one on each side of the eartozache or shield, inclosing the hieroglyphic name of a king, having the signification of dominion.

The lotus, or water lily of the Nile, is the type of the inundations from which Egypt derives its fruitfulness.

The zigzag is the type of the water, or of the Nile itself. The ancient signification of the zigzag is still preserved in the zodiac sign of the water-carrier or aquarius.

The wave-scroll represents water in motion.

The fret is a type of the labyrinth of Lake Aloeris, with its twelve palaces and three thousand chambers, indicating in their turn the twelve signs of the zodiac, and the three thousand years of transmigration which the wandering soul is condemned to undergo.

The Egyptians systematically varied their pillars in the same colonnade; two alike with their decorations complete were never placed together except as a pair of opposites. The varieties may be reduced to three essential forms, viz., truncated lotus bud, lotus bell, Isis head. Every capital is a variety of one of these essential forms, but the lotus or papyrus bell of the middle period is much the more common.

The Egyptian style influenced the Jew, the Greek, and the Persian. After Cambyses had plundered Thebes, he carried a colony of Egyptian artists with him to Persia.

Examples of lotus bud and lotus bell capitals and of corresponding bases of columns.

The bull, which figures largely in the Persepolitan sculpture, is explained as signifying the overthrow of the Assyrian power by the Persians.

In Egypt we find grandeur of proportions, simplicity of parts, and splendor or costliness of material—gold, silver, ivory, precious stones, and color —as the great art characteristics.

We also find the prevailing feature of Asiatic art to be sumptuousness. Examples : the works of the tabernacle, the temple of Solomon, the buildings of Semiramis and Nebuchadnezzar, and the palaces of the Persian kings.

Jewish ornament, like the Egyptian, appears to be purely representative. The only elements mentioned in Scripture are : the almond, the pomegranate, and the palm-tree, the lily or lotus, oxen, lions, and cherubim.

Extending our view still farther east, we find the fantastic the most striking feature of Hindu art.

The Egyptian was a painted style. Its architecture was marked by the use of oblique lines. Length of line, firmness of drawing, severity of form, and subtlety- of curvature are its characteristics. Dignity, sternness, simplicity bordering on monotony, extreme solidity, amounting to -heaviness, was the expression of the national character of the people.

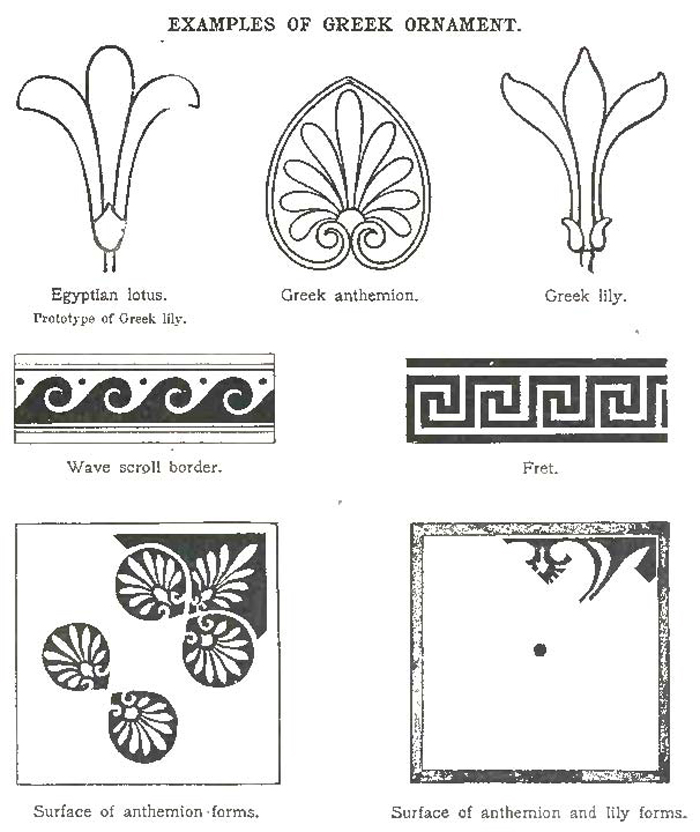

It is not till we come to Greece that we find the habitual introduction of forms for their own sake, for their esthetic value purely as ornaments, and this is a very great step in art.

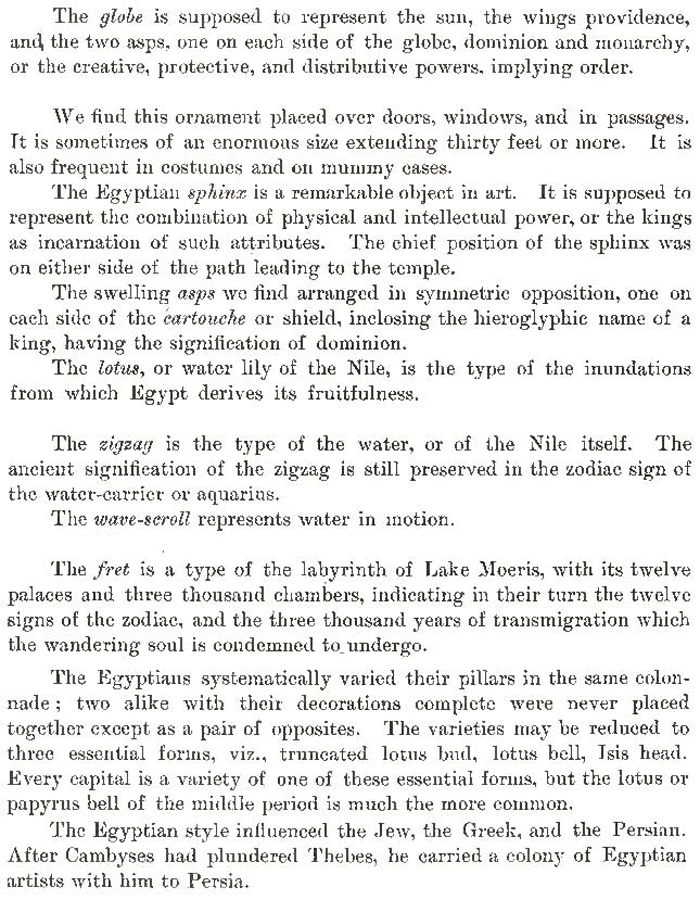

In the following drawing the winged ,globe may be seen over the door—an example of the placing of this ornament in architecture. The meaning of the symbol and its. position are suggested in the familiar lines — "Cover my defenseless head With the shadow of Thy wing."

An inscription at Edfou says that Thoth ordered that this emblem should be carved over every doorway in Egypt.

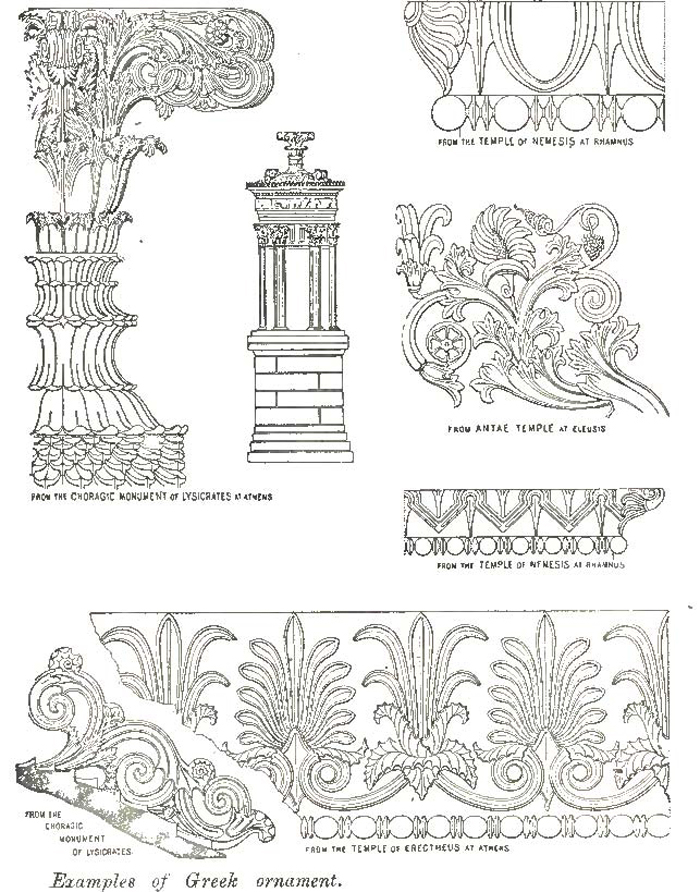

Three periods of Greek Style: —

Doric = Echinus and astragal.

Ionic = Doric and horns or volutes.

Corinthian = Acanthus.

Greek ornament owes its originality to the substitution of the esthetic for the symbolic principle.

The Doric age covers the first four centuries, from Incubus of Samos to Pericles.

The most important manufacture of the period of which remains exist, was that of the terra-cotta vases.

There are two classes of painted Greek pottery, the black and the yellow; that is, those vases that have black figures and ornaments, the ground of the vase being left the color of the clay ; and those vases that have the ground painted black, and the figures left the color of the clay.

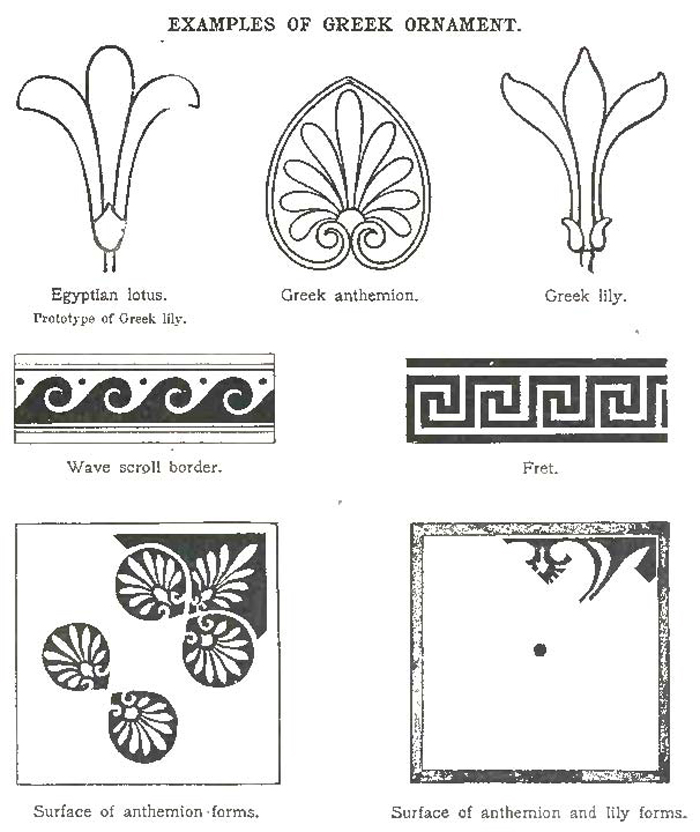

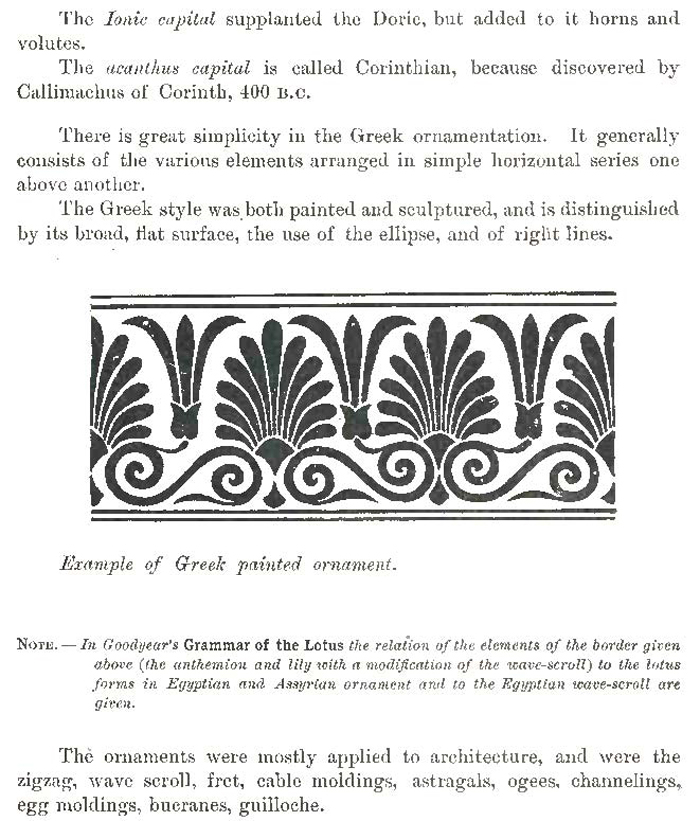

The anthemion, or flower ornament, is more than the mere honeysuckle ; it is this flower alternated with the lily or analogous forms.

Occasionally in the Doric period emblematic ornaments were used with regard to the mysteries, sacrifices, funeral rites, etc., but these instances are rare.

The rainless seasons of Egypt developed massive flat roofs ; so the rainy seasons of Greece rendered the sloping roof necessary, the gable of which the Greeks eventually developed into their beautiful pediment.

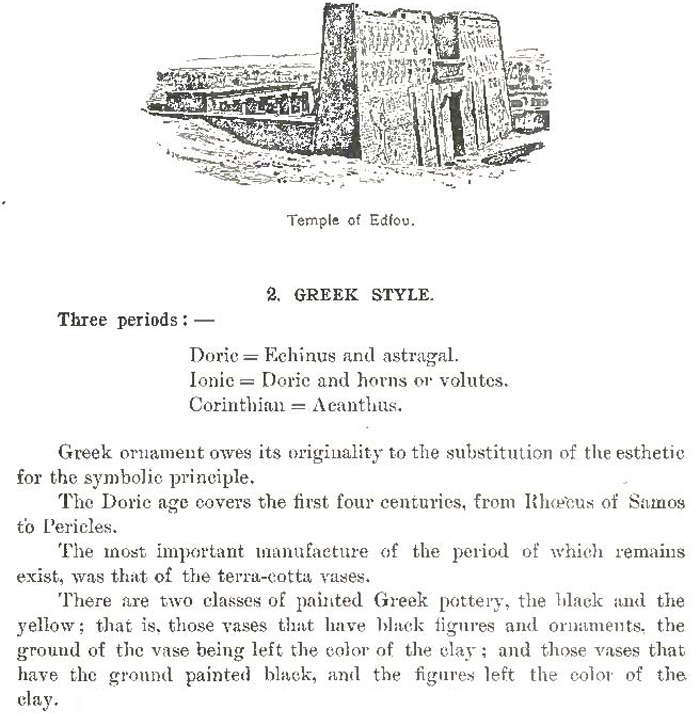

The Doric order may be descriptively termed the echinus order, as the echinus is the ornament of the period.

"Echinns, bold and simply marked, With astragal of beads and pearls Of shining gold on ground of red."

Foliage performs a very secondary part in this period.

The Doric capital consists of a round flat cushion called the echirals, and a large square abacus.

The Ionic capital supplanted the Doric, but added to it horns and volutes.

The acanthus capital is called Corinthian, because discovered by Callimachus of Corinth, 400 B.C.

There is great simplicity in the Greek ornamentation. It generally consists of the various elements arranged in simple horizontal series one above another.

The Greek style was both painted and sculptured, and is distinguished by its broad, flat surface, the use of the ellipse, and of right lines.

NOTE.—In Goodyear's Grammar of the Lotus the reldion of the elements of the border given above (the anthemion and lily with a modification of the wave-scroll) to the lotus forms in Egyptian and Assyrian ornament and to the Egyptian wave scroll are given.

The ornaments were mostly applied to architecture, and were the zigzag, wave scroll, fret, cable moldings, astragals, ogees, channelings, egg moldings, bucranes, guilloche.

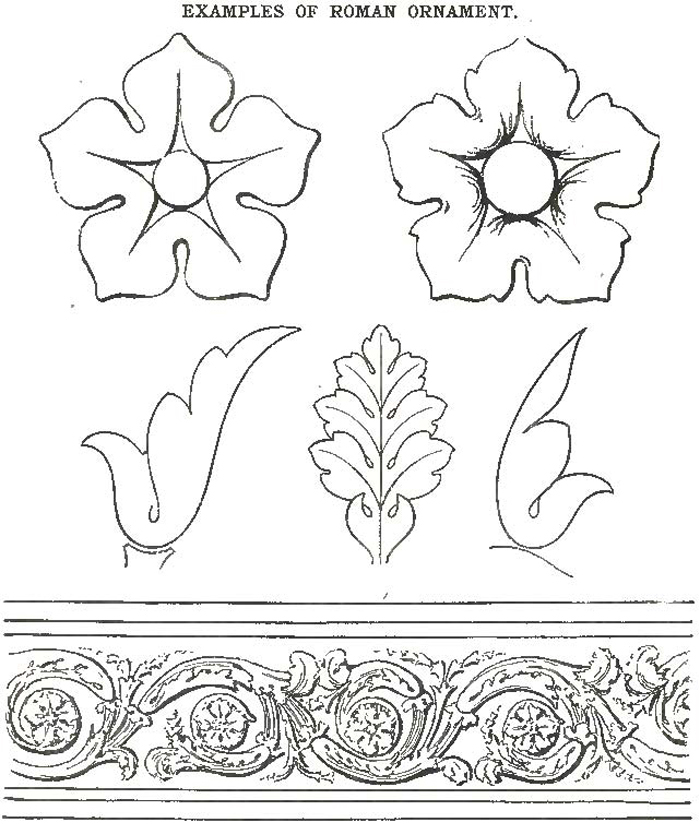

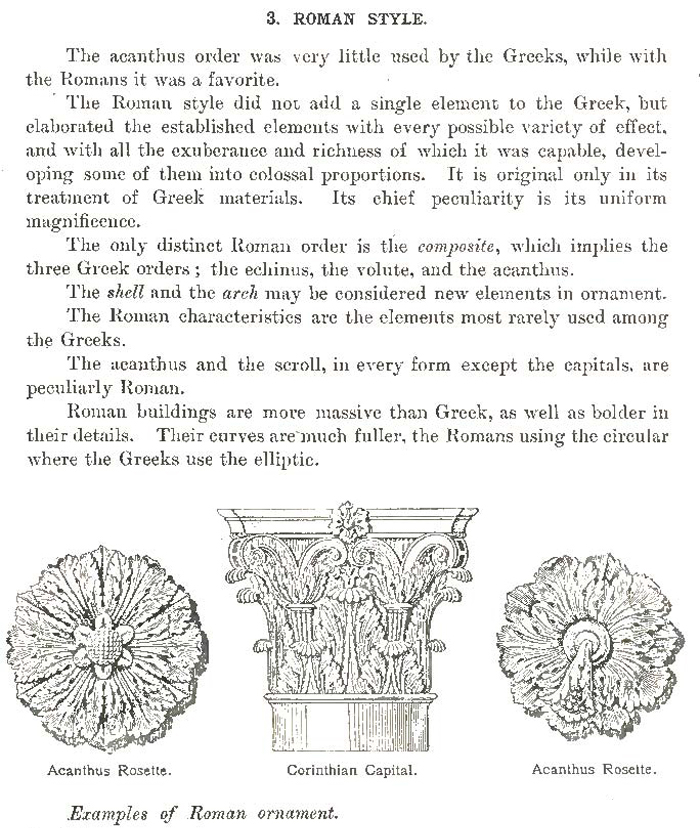

The acanthus order was very little used by the Greeks, while with the Romans it was a favorite.

The Roman style did not add a single element to the Greek, but elaborated the established elements with every possible variety of effect, and with all the exuberance and richness of which it was capable, developing some of them into colossal proportions. It is original only in its treatment of Greek materials. Its chief peculiarity is its uniform magnificence.

The only distinct Roman order is the composite, which implies the three Greek orders ; the echinus, the volute, and the acanthus.

The shell and the arch may be considered new elements in ornament. The Roman characteristics are the elements most rarely used among the Greeks.

The acanthus and the scroll, in every form except the capitals, are peculiarly Roman.

Roman buildings are more massive than Greek, as well as bolder in their details. Their curves are-much fuller, the Romans using the circular where the Greeks use the elliptic.

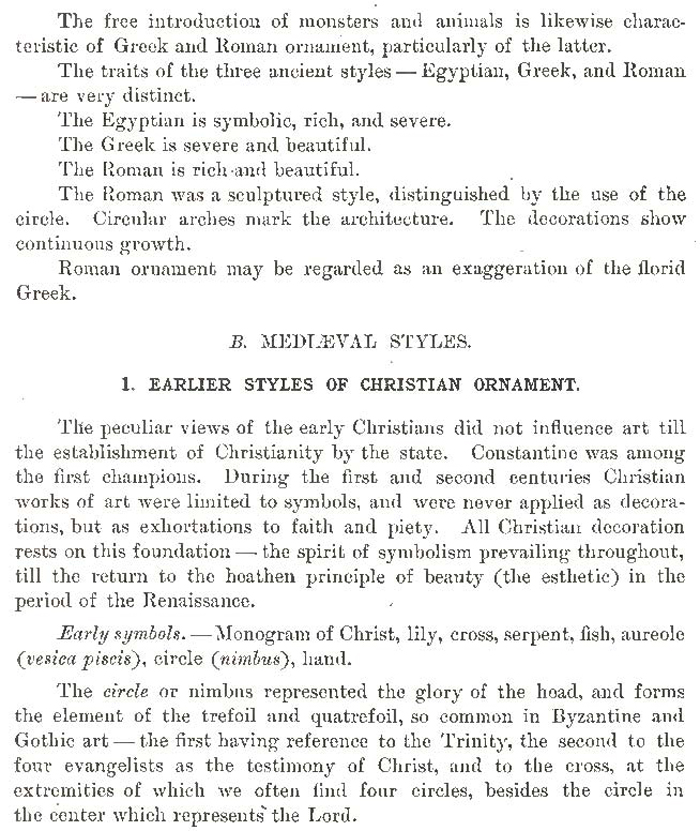

The free introduction of monsters and animals is likewise characteristic of Greek and Roman ornament, particularly of the latter.

The traits of the three ancient styles Egyptian, Greek, and Roman —are very distinct.

The Egyptian is symbolic, rich, and severe.

The Greek is severe and beautiful.

The Roman is rich .and beautiful.

The Roman was a sculptured style, distinguished by the use of the circle. Circular arches mark the architecture. The decorations show continuous growth.

Roman ornament may be regarded as an exaggeration of the florid Greek.

The peculiar views of the early Christians did not influence art till the establishment of Christianity by the state. Constantine was among the first champions. During the first and second centuries Christian works of art were limited to symbols, and were never applied as decorations, but as exhortations to faith and piety. All Christian decoration rests on this foundation — the spirit of symbolism prevailing throughout, till the return to the heathen principle of beauty (the esthetic) in the period of the Renaissance.

Monogram of Christ, lily, cross, serpent, fish, aureole (vesica piscis), circle (nimbus), hand.

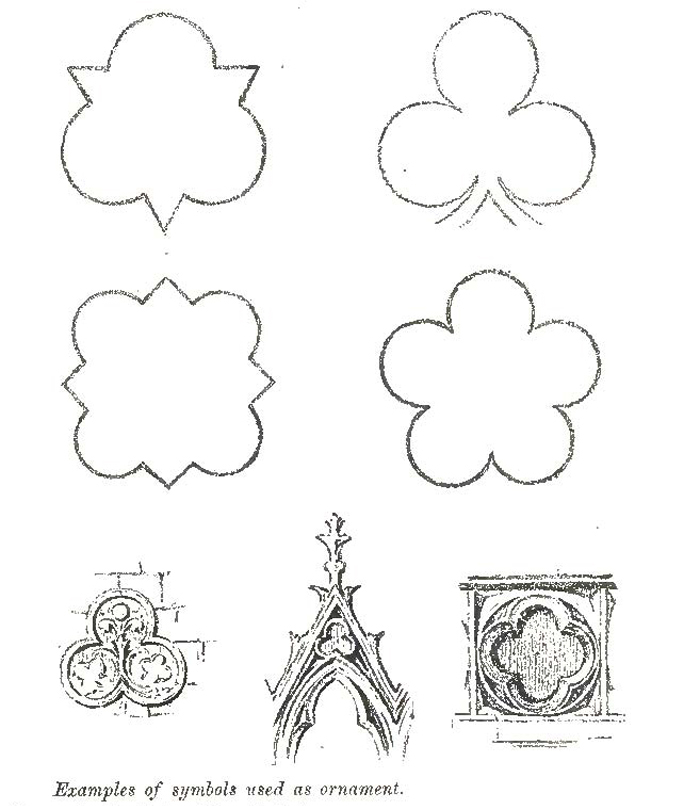

The circle or nimbus represented the glory of the head, and forms the element of the trefoil and quatrefoil, so common in Byzantine and Gothic art — the first having reference to the Trinity, the second to the four evangelists as the testimony of Christ, and to the cross, at the extremities of which we often find four circles, besides the circle in the center which represents the Lord.

Thus, figures or combinations of three, four, or five circles are common in mediaeval art, and have sacred significations. Many crosses are composed entirely of five circles as principals, or are prominently decorated with them.

In crosses composed simply of five circles, the center circle has reference to our Lord, and the other four to the evangelists. Occasionally the symbolic images of the evangelists — the angel, the lion, the ox, and the eagle — are represented within these circles.

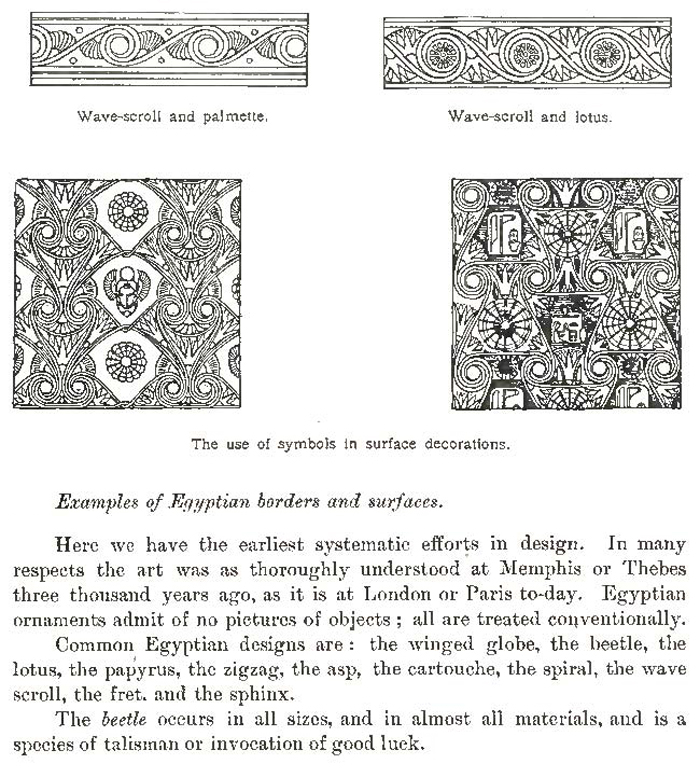

The lily or fleur-de-lis is the emblem of the Virgin and of purity. It is as common in Christian decoration as the lotus in that of Egypt.

The serpent figures largely in Byzantine art, as the instrument of the fall, and as a type of the redemption.

The cross planted on the serpent is found sculptured on Mount Athos: The cross surrounded by the so-called runic knot is only a Scandinavian version of the original Byzantine image — the crushed snake curling around the stem of the avenging cross. The cross with two scrolls at the foot of it, typifying the snake, is another form of the same.

The hand is also a characteristic element of early Christian art.

There is a distinction between the Greek and the Latin form. The Greek symbolizes our Lord, expressing His monogram by placing the thumb on the third finger, and slightly curving the second and fourth. The Latin displays the thumb, the first and second fingers extended. The Roman prelate blesses in the name of the Trinity ; the Greek, in the name of our Lord.

The dome has its reference to the vault of heaven and the glorification of our Lord.

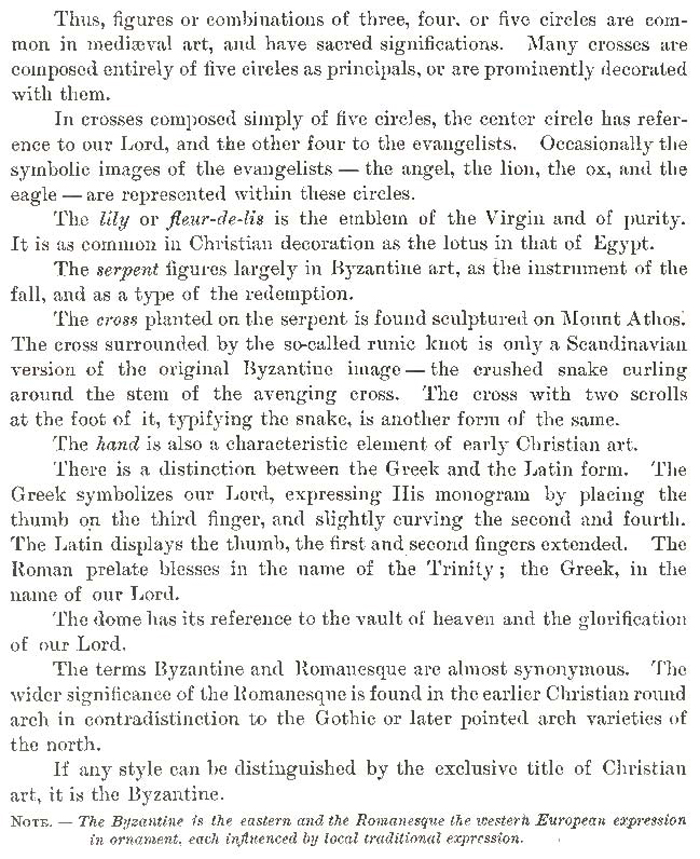

The terms Byzantine and Romanesque are almost synonymous. The wider significance of the Romanesque is found in the earlier Christian round arch in contradistinction to the Gothic or later pointed arch varieties of the north.

If any style can be distinguished by the exclusive title of Christian art, it is the Byzantine.

NOTE. - The Byzantine is the eastern and the Romanesque the teesterh European expression in ornament, each influenced by local traditional expression.

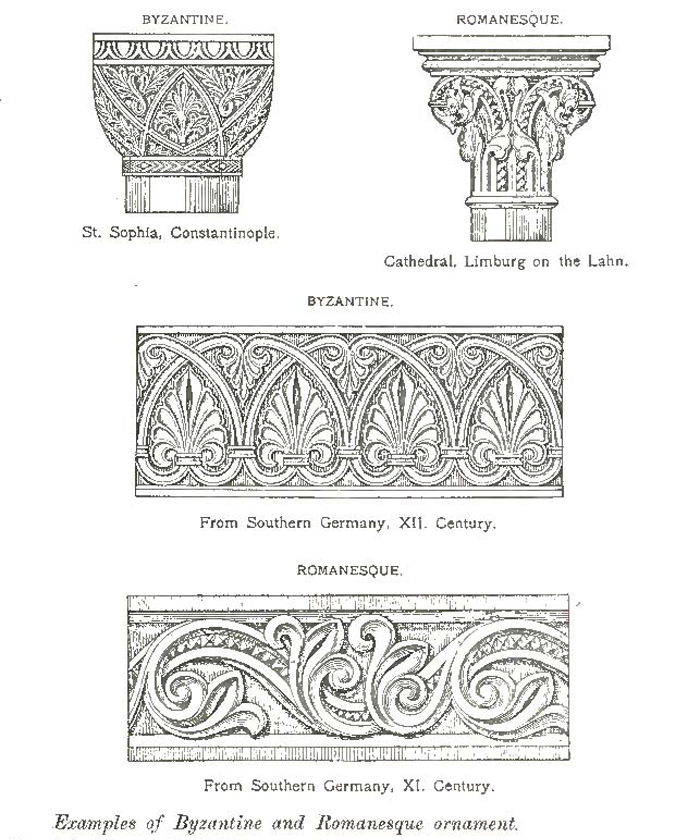

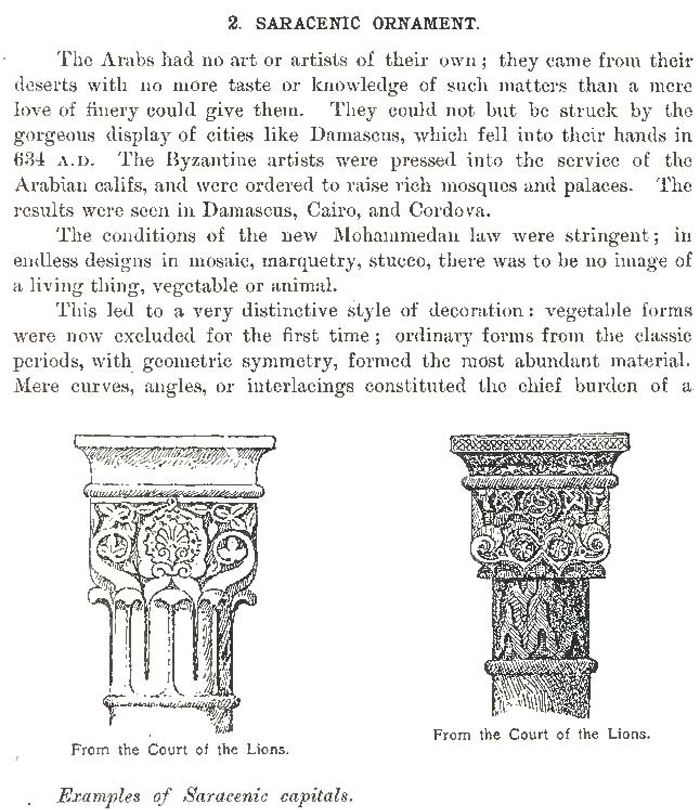

The Arabs had no art or artists of their own ; they came from their deserts with no more taste or knowledge of such matters than a mere love of finery could give them. They could not but be struck by the gorgeous display of cities like Damascus, which fell into their hands in 634 A.D. The Byzantine artists were pressed into the service of the Arabian califs, and were ordered to raise rich mosques and palaces. The results were seen in Damascus, Cairo, and Cordova.

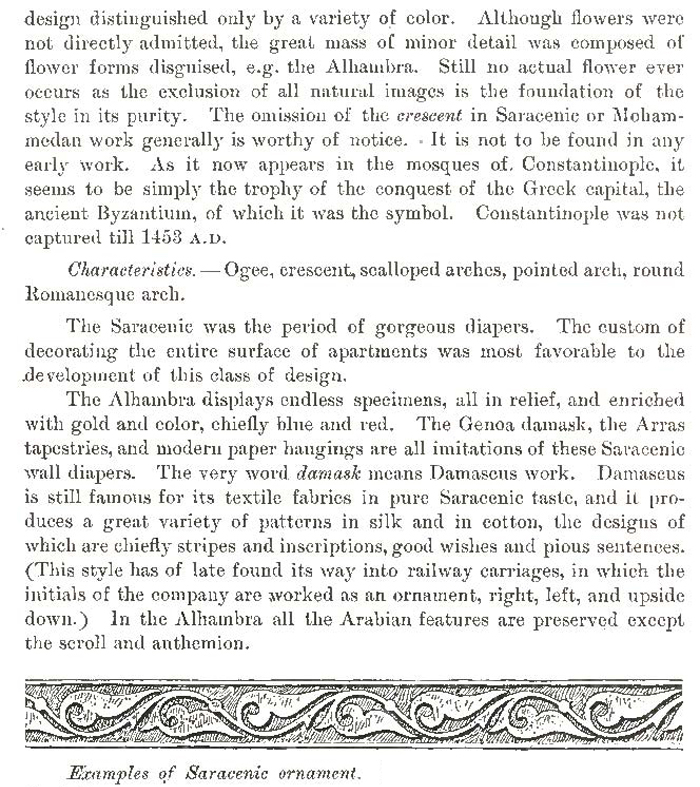

The conditions of the new Mohammedan law were stringent ; in endless designs in mosaic, marquetry, stucco, there was to be no image of a living thing, vegetable or animal. This led to a very distinctive style of decoration : vegetable forms were now excluded for the first time ; ordinary forms from the classic periods, with geometric symmetry, formed the most abundant material. Mere curves, angles, or interlacings constituted the chief burden of a design distinguished only by a variety of color. Although flowers were not directly admitted, the great mass of minor detail was composed of flower forms disguised, e.g. the Alhambra. Still no actual flower ever occurs as the exclusion of all natural images is the foundation of the style in its purity. The omission of the crescent in Saracenic or Mohammedan work generally is worthy of notice. • It is not to be found in any early work. As it now appears in the mosques of, Constantinople, it seems to be simply the trophy of the conquest of the Greek capital, the ancient Byzantium, of which it was the symbol. Constantinople was not captured till 1453 A.D.

Ogee, crescent, scalloped arches, pointed arch, round Romanesque arch.

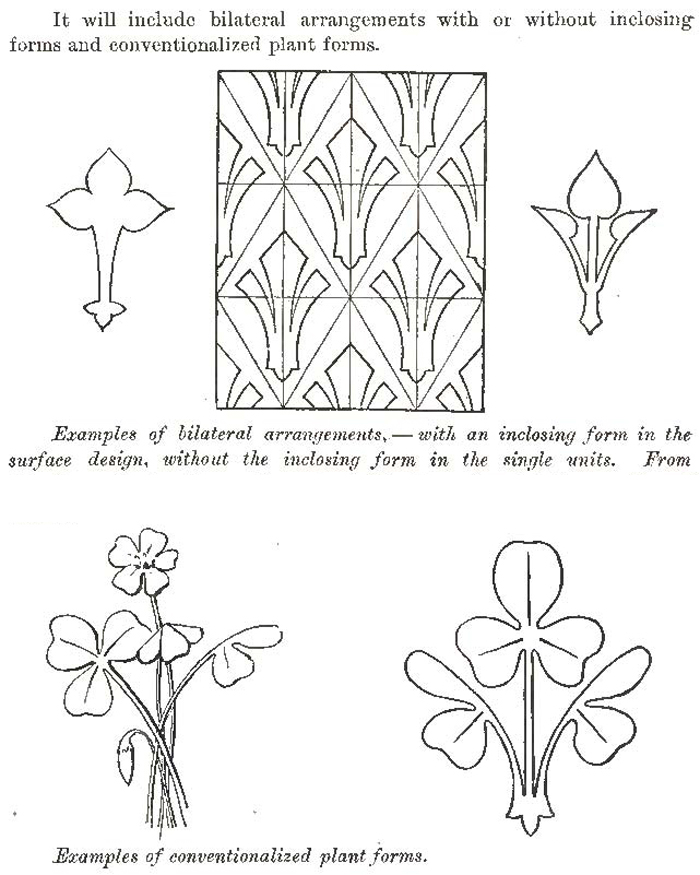

The Saracenic was the period of gorgeous diapers. The custom of decorating the entire surface of apartments was most favorable to the .development of this class of design.

The Alhambra displays endless specimens, all in relief, and enriched with gold and color, chiefly blue and red. The Genoa damask, the Arras tapestries, and modern paper hangings are all imitations of these Saracenic wall diapers. The very word damask means Damascus work. Damascus is still famous for its textile fabrics in pure Saracenic taste, and it produces a great variety of patterns in silk and in cotton, the designs of which are chiefly stripes and inscriptions, good wishes and pious sentences. (This style has of late found its way into railway carriages, in which the initials of the company are worked as an ornament, right, left, and upside down.) In the Alhambra all the Arabian features are preserved except the scroll and anthemion.

The Saracenic is distinguished for its geometric tracery, strap work, inscriptions, and wonderful coloring.

It has been said by a competent judge that " Every principle which we can derive from the study of the ornamental art of other nations is not only present here, but was more universally and truly obeyed by the Moors than by any other people."

It has also been said that there are really but three pure styles, all others being derived from them, viz. : Egyptian, Greek, Saracenic.

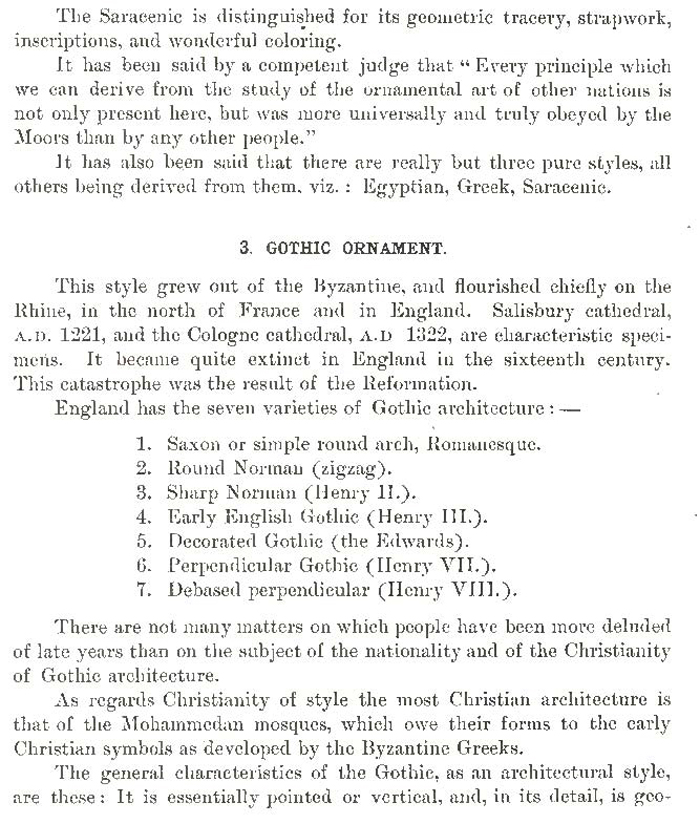

This style grew out of the Byzantine, and flourished chiefly on the Rhine, in the north of France and in England. Salisbury cathedral, A.D. 1221, and the Cologne cathedral, A.D 1322, are characteristic specimens. It became quite extinct in England in the sixteenth century. This catastrophe was the result of the Reformation.

1. Saxon or simple round arch, Romanesque.

2. Round Norman (zigzag).

3. Sharp Norman (Henry II.).

4. Early English Gothic (Henry III.).

5. Decorated Gothic (the Edwards).

6. Perpendicular Gothic (Henry VII.).

7. Debased perpendicular (Henry VIII.).

There are not many matters on which people have been more deluded of late years than on the subject of the nationality and of the Christianity of Gothic architecture.

As regards Christianity of style the most Christian architecture is that of the Mohammedan mosques, which owe their forms to the early Christian symbols as developed by the Byzantine Greeks.

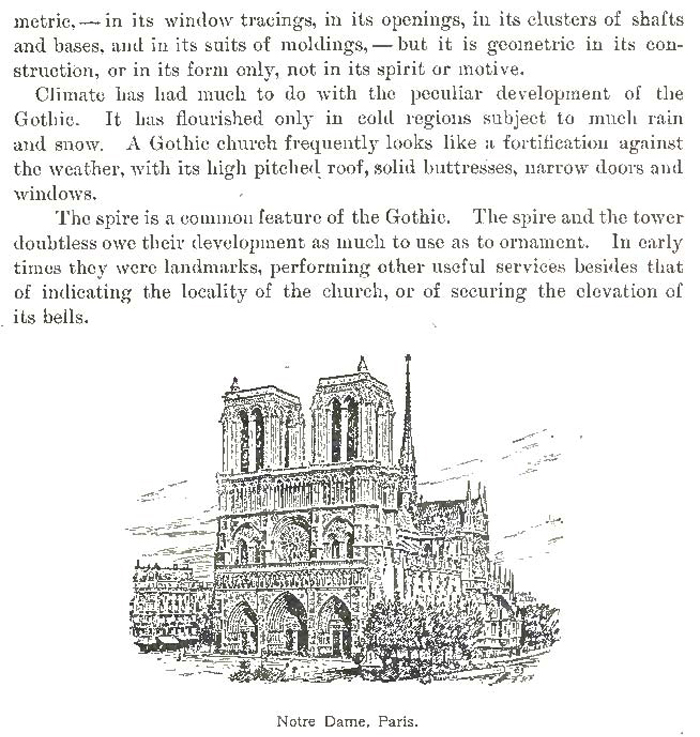

The general characteristics of the Gothic, as an architectural style, are these : It is essentially pointed or vertical, and, in its detail, is geometric, — in its window tracings, in its openings, in its clusters of shafts and bases, and in its suits of moldings, — but it is geometric in its construction, or in its form only, not in its spirit or motive.

Climate has had much to do with the peculiar development of the Gothic. It has flourished only in cold regions subject to much rain and snow. A. Gothic church frequently looks like a fortification against the weather, with its high pitched roof, solid buttresses, narrow doors and windows.

The spire is a common feature of the Gothic. The spire and the tower doubtless owe their development as much to use as to ornament. In early times they were landmarks, performing other useful services besides that of indicating the locality of the church, or of securing the elevation of its bells.

Ornamentally, the Gothic is the geometric and pointed element elaborated to its utmost. Its only peculiarities are- in the combination of detail in its decorations, the conventional and the geometric prevailing at first, and afterward these combined with the elaboration of natural objects.

The Byzantines never did this ; the Gothic vesicas, trefoils, quatrefoils, cinquefoils, and geometric varieties are infinite. Early English Gothic presents the following characteristics : mullions instead of piers, windows of several lights, flying buttresses, crocketed pinnacles, complicated moldings, clustered columns, round capitals, an extensive application of foliage, with the trefoil leaf. The dog-tooth molding was also another characteristic ; in its original form it was a simple vesica cross, but being contracted to fill hollows, it assumed its present form in the early Plantagenet period.

It is the geometric tracery which stamps a design as Gothic. Examples : Tudor-flower, fleur-de-lis, crocket leaf, trefoil, vine scroll, etc. In this style Norman and classic ornament are not admissible ; also tropical plants would be inconsistent.

This name implies the revival of art or its rebirth. It was the revival of the classic order of architecture, the ancient art of Greece and Rome in the place of the Middle Age styles. The essence of all Middle Age art was symbolism, and the transition from symbolism to the unalloyed principles of beauty is the great feature of the revival. Art was wholly separated from religion in the Renaissance, but this transition was developed gradually.

In Italy the change first began about the year 1300. This was in some degree owing to the crusades, but more specially to the Latin conquest of Constantinople in 1204, which displayed many treasures of ancient art to the Venetians. Four ancient bronze horses, a Christian trophy of this Venetian crusade, still adorn the facade of St. Mark's. The beginning of the Renaissance period may be known as the trecento, the more finished as the cinquecento, and the latest, the most modern, as the Louis Quatorze.

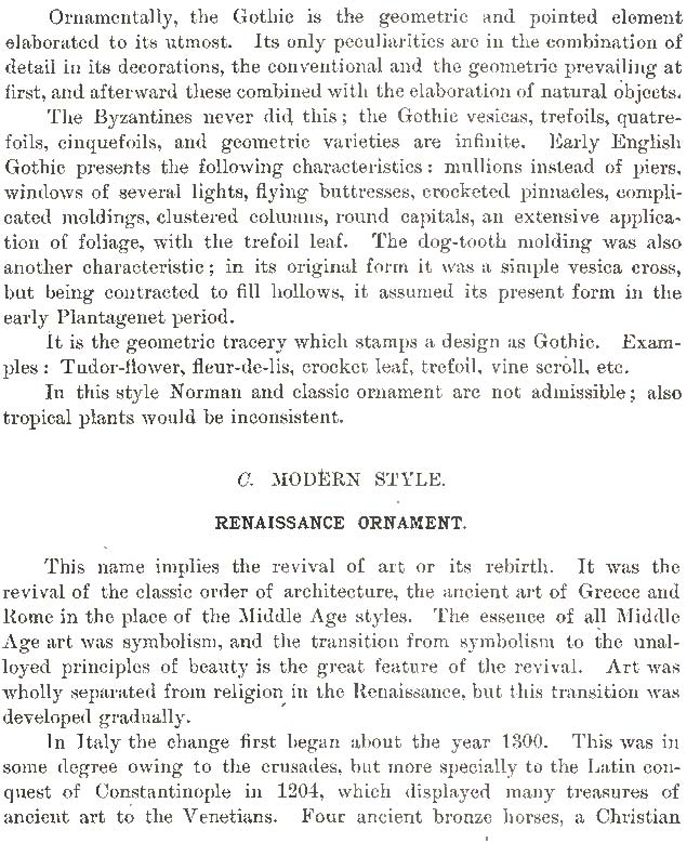

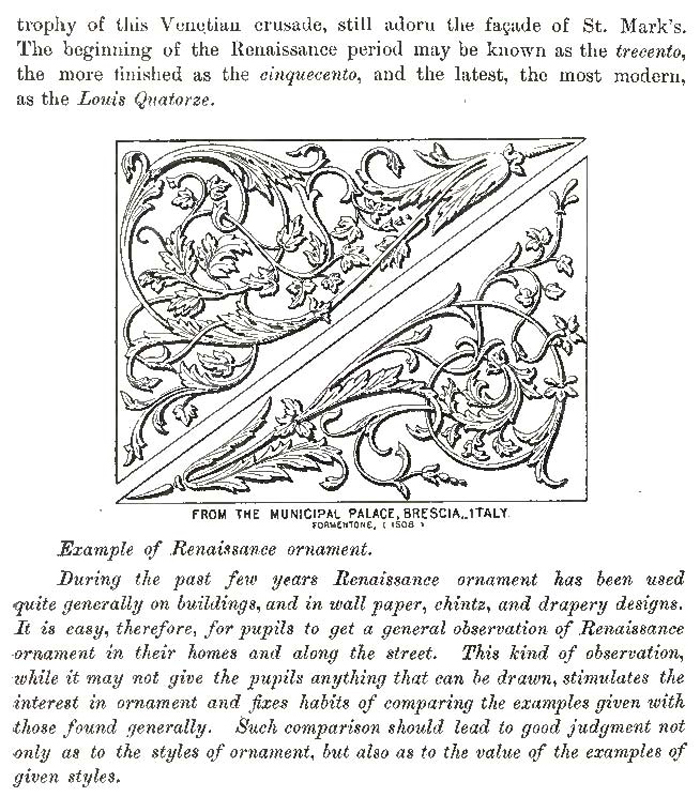

Example of Renaissance ornament. From Parallels of Historic Ornament, sheet of Renaissance style.

During the past few years Renaissance ornament has been used quite generally on buildings, and in wall paper, chintz, and drapery designs. It is easy, therefore, for pupils to get a general observation of Renaissance ornament in their homes and along the street. This kind of observation, while it may not give the pupils anything that can be drawn, stimulates the interest in ornament and. fixes habits of comparing the examples given with those found generally. Such comparison should lead to good judgment not only as to the styles of ornament, but also as to the value of the examples of given styles.