Home > Directory Home > Drawing Lessons > How to Draw Caricatures & Cartoon Faces > Human Anatomy & Figure Drawing for Artists and Caricaturists

Human Anatomy & figure drawing for artists, cartoonists, and caricaturists

|

GO BACK TO THE HOME PAGE FOR CARICATURE DRAWING TUTORIALS

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

ARTISTIC ANATOMY

ARTISTIC anatomy takes into consideration those parts of the human body which are visible to the eye, or which affect by their form or action these visible exterior parts. The basic, bony structure of the human frame is covered, at the points particularly, by a strong envelope entitled Periosteum. This, in turn, is covered by the muscles, which are placed in layers and thinly inclosed by their own special envelope. The muscles are formed by fleshy fibers and sinewy parts running in various directions, according to their particular uses.

These component parts of the figure are covered by the membrane commonly termed the skin.The actions of the principal muscles can be plainly seen through this elastic covering. There is a common tendency among artists to over-accentuate this easily observed play of the muscles; and, while an expert knowledge of them is apt to lead in this direction, it is distinctly a good fault. A picture of a figure in which the muscles are somewhat exaggerated carries more conviction than one in which there is no suggestion of the anatomical construction beneath the skin.

The great antique statues invariably indicated with the utmost clearness the muscular development of the human figure. To study these statues carefully (which does not necessarily mean to draw them) cannot fail to give a better understanding of the practical application of a knowledge of artistic anatomy.

The skeleton is the framework, or foundation, of the human figure. Upon it the superstructure is dependent. It regulates the capabilities, power, and size of its owner, and is strong enough to suspend and hold the remaining portions of the body in any necessary position.

The skeleton is composed of about two hundred parts, which need not be named in detail in a work of this character. Some of these bones, when viewed in cross-sections, are triangular, some four-sided, and others round; still others show all of these forms combined in their different parts to meet special requirements.

Broadly speaking, there are three sorts of bones in the human figure: short, long, and broad.The entire mass of the bony structure may be broadly divided into the extremities and the trunk. With the trunk are included the head, the ribs, the breastbone, the backbone, and the bones of the hips.

THE HUMAN SKELETON.

The arms are known as the superior extremities and the legs as the inferior extremities.The skull, or bony portion of the head, is subdivided into the cranium and the face. There are twenty-four bones in the backbone, or vertebral column; seven of these are in the neck, twelve in the back or ribs, and five in the loins. An average spine or backbone is from two feet four inches to two feet eight inches long, without taking its base into consideration. When seen from the side, it is greatly curved in form : concave at the neck, convex at the back, and slightly concave at the loins. Viewed from the front or rear, its tendency is to slant toward the left with a slight curve; the purpose of this slant is not known. The entire column is flexible, owing to cartilage discs between the bony section; these discs are elastic enough to permit the spine to move in various directions without injuring what is known as the spinal marrow, which extends almost throughout the length of the column. lhe spine moves principally at the neck and loins.

The general bearing of the figure depends, to a great extent, upon the curve of the spinal column. The ribs are attached to either side of this column and are twenty-four in number. They consist of bone and cartilage. The seven upper ribs on each side are termed true ribs; the others are called false ribs and are not attached, like the true ribs, to the breastbone. The general inclination of the false ribs is downward from the back. The ribs form a basket-like shape incasing all the vital organs and forming a basis for a fleshy covering which, differing in a marked way from the general contour of the ribs, is distinctly affected in form by them.

The breastbone is in the front and center of the chest. In infancy the breastbone consists of several sections which gradually acquire solidity with advancing age until, in an adult, they are practically a single bone. The general inclination of the breastbone is forward and downward, this angle being affected considerably by climatic or racial causes and, in an individual, by his daily occupation or habits. From twenty to twenty-five degrees is the angle for the breastbone which has generally been conceded to be the average or normal one in the male. In the female this angle is somewhat greater.

The female neck, in its bony portion, is considerably straighter than the male.The collar bones are attached to the upper end of the breastbone; from the breastbone they curve outward and, toward their outer ends, reverse their direction. They are more pronounced in men than in women. Their union with the breastbone leaves a small follow commonly called the pit of the neck. The large, strongly constructed bones forming the cavity occupying the center of the osseous structure of the human figure is called the pelvis. The pelvis presents a curved bony wall projecting itself downward and forward, and at its top is a strong, curved edge to which powerful muscles are attached. This part of the figure is larger and roomier in the female than in the male and its shape considerably different.

The arms are attached to the shoulder blades by powerful ligaments. The upper part of the arm contains one long bone, partly round and growing larger at the top to form a rounded cap or head, and several protuberances which are covered by cartilage and fit snugly into a suitable space in the blade bone, which is also lined with cartilage. The lower end of this bone is also enlarged and, by a beautiful and delicate arrangement, is fitted to the twin bones of the forearm in such a manner as to allow one to turn over the other, thus permitting the hand to twist in either direction.

HUMAN SKULL.

The various bones of the wrist are attached directly to the two bones of the forearm; these are succeeded in turn by the bony portions of the back and palm of the hand. To these latter bones are attached the finger joints. The legs contain bones similar in arrangement and number to those of the arm, though different in shape to fit them to their particular uses. The thigh bone is, in similar manner to the bone of the upper arm, partly round. It is also topped with a round head or cap which fits into a suitable cavity and forms a ball-and-socket joint of great power. Like the bone of the upper arm again, it has at its top, in addition to a globular head, certain protuberances the largest one of which serves as a point of attachment for important muscles. The lower end of the thigh bone broadens to form two parts to which the principal bone of the leg is attached in a hinge-like manner. Like the juncture of the wrist bones to the lower part of the arm, the bony parts of the ankle and instep join the bones of the lower leg and toes. To one who would become an expert draughtsman of the figure, practice in drawing the skeleton will be found an important aid; for the action, or general swing and direction of a figure (whether at rest or in motion) is always determined by the unseen skeleton.

From the standpoint of the anatomist the skull consists of two parts : the cranium and face. As the forehead is usually considered a part of the faceparticularly in art—the student may, for convenience sake, consider these as one. Draughtsmen take the Caucasian, or European, as a standard of comparison, and the plate shown in this work relating to this subject is made in accordance with this standard. The skull is composed of several bones, most of which are separated by irregular saw-like lines dovetailing into each other. Some of the interior bones of the skull are not necessary for the artist to consider.

The bones of the forehead vary greatly in races and individuals. With the European head as a standard of comparison, it may be set down as a fixed rule that the forehead is as long as the nose. The spherical shape of the cranium, or upper part of the head, is not materially affected in form by its light covering of skin and muscle. The face contains much more fleshy covering, in which the play of muscle is so subtle and intricate as to form a problem more perplexing to the artist than any other part of the human figure. The action of the muscles of the face is, as a rule, in an opposite direction from the wrinkles or marks which they cause. It is by the action of these muscles (which in turn are animated and controlled by the brain) that the various emo- tions of the soul are plainly depicted upon the countenance. For this reason the muscular development of these parts should be studied with most careful attention. In considering the general shape of the face, due attention should be given to the fact that many of its prominent parts are caused by bony protuberances.

It should be noted that the large bone at the back and base of the skull projects quite strongly. This is particularly noticeable in infants and bald people.

The bones just back of the ears form a point of attachment to a pair of powerful neck muscles. The arched projections over the eyes are greatly varied in shape and size in individual cases and play a considerable part in the general character of every face. This is also true of the curved line at each side of the forehead, just above the outside tips of the eyebrows. The cheek-bone and jaw-bone also play important parts in facial characteristics.

FACIAL AND NECK MUSCLES.

The important muscles of the face are for the most part readily understood and are all that are necessary to note in a book of this character. The frontal muscle begins at the inside upper edge of the orbit of the eye, then rises obliquely and unites with a system which covers the entire skull. The forehead is wrinkled by the action of this muscle and many emotions are indicated by its play. The temporal muscle starts at the top and side of the forehead, and descends through the cheek to the lower jaw-bone, which it has the power to raise and press against the upper jaw. Another muscle—primarily used as an aid to mastication—starts at the upper jaw and the lower front of the cheek-bone. It descends on the outer side of the under jaw-bone, being affixed to it and reaching nearly to the end of the mouth. This muscle acts in connection with the temporal muscle, and the two swell and contract simultaneously. The action of these particular muscles is very noticeable when the mind is violently agitated by passion, pain, or any other strong emotion, or during strenuous muscular exertion.

A series of fleshy fibers circle the eyes and operate the eyelids. These muscles are not attached to the bones upon which they rest. The nostrils and upper lip are controlled by the elevator muscle of the nostril, which arises in a double tendon at the junction of the upper jaw and the base of the nose. This muscle ends in a fan-like shape, spreading over the nostrils and the upper lip; in connection with other muscles, it forms the furrow separating the cheek and the nostrils. At the root of the nostrils, what is called the compressor muscle originates. This muscle terminates in a membrane which covers the entire nose and reaches well into the forehead. It can wrinkle the skin of the nose or compress the nostrils. Just below the orb of the eye the elevator muscle of the upper lip starts, running down at a gentle angle to the upper lip, which it has the power to draw outward and upward. The action of this muscle is evident in laughter and other emotions. Another muscle acts in unison at its outside edge, descending in a parallel direction. A fleshy muscle is attached to the cheek-bone and runs into the angle of the mouth. It can draw the corner of the mouth and under lip toward its points of attachment, and forms the prominent ridge shown in the cheek of a laughing face. The facial muscles, thus far considered, have for their function the upward pull of the features. Another set of muscles exert a downward pull and are called the depressors. One of these latter originates underneath the lower jaw, where it is quite broad. As it reaches upward it becomes narrower, forming a pyramidical shape.

At its upper end it curves around the angles of the upper lip and, in accordance with its name, has the power of depressing the corners of the mouth. The mouth is closed by a special muscle, which is so interwoven with its neighbors as to almost become a part of them. It is capable of affecting the face in various ways and can compress the lips against the teeth or against each other, and acts contrary to other muscles in controlling laughter. The trumpeter, as its name implies, is used to contract the lips to form an orifice, through which the breath may be blown into any wind instrument. Generally speaking, the muscles of the face expand in pleasurable emotions, and contract in violent passions. They are intimately connected with those of the neck.

The forward and rotary motions are the most common actions of the head. They principally depend upon two of the neck-bones. The action of bowing has its most important movement where the skull joins the first vertebra of the spinal column. The rotary action, however, takes place at the second vertebra, which contains a kind of pivot especially adapted for this purpose. The head is capable of a slight movement toward either shoulder, not exceeding a quarter of a circle to the right or left. Other movements of the head—either sidewise or slanting—are jointly actuated by the five other vertebrae of the neck, in connection with the two previously alluded to.

The vertebrae of the neck are inclosed by a network of various muscles—all in pairs. These muscles are capable of imparting various movements to the joints which they surround. The two powerful and very prominent muscles at either side of the neck assist in almost all its actions, and are attached at the top behind the ear. When the head is turned to one side the neck wrinkles on that side and the corresponding tension of its twin muscle takes place on the opposite side. During this action the projection which usually shows quite plainly in the front of a man's neck ( and is commonly termed Adam's apple) comes into much greater prominence. This muscle shows very plainly in aged and thin persons, while in a well-formed woman it is hardly visible.

A flat, broad muscle completely covers the back of the neck, running down to a point in the middle of the back. It is shaped much like a monk's cowl, and its Latin name is founded on this similarity. It sends out fibers which radiate in various directions, the ends of these fibers attaching themselves to the shoulder blades and collar bones. It will be readily understood, owing to the complex nature of this muscle and its system of tendonous attachments, that its actions are many. Its principal use is to pull the head downward and backward, in which instance the skin of the back of the neck takes characteristic folds. A flat, broad muscle attaches to the skin of the upper part of the chest, ascends into the lower jawbone and thence toward the ear. It aids in depressing the ends of the mouth and a portion of the cheek.

THE SHOULDER-JOINT.

The shoulder-joint demands the most studious observation and study in order to comprehend its intricate movements. The shoulder blade is placed against the head of the upper arm bone. The collar bone is attached to both of these bones by powerful ligaments, which form an arch under which the upper arm bone hangs, the whole being incased by several muscles which bind them together. The bladebone moves freely over the back of the ribs, and the collar bone, being attached to it, responds to its motions.The head of the upper arm bone, having a socket-joint, can move in nearly every direction; the various movements affect the adjoining bones to a certain extent. For instance, in raising the arm, the blade-bone responds; the outer edge of the collar bone rises also, moving on its inner end as a pivot. In pushing, striking, or pulling with the arm, the bladebone slides over the ribs, and the angle of the collar bone is determined by the violence of the action.

A muscle—triangular in shape, like the D of the Greek alphabet from which it gets its name—partly covers the bones which form the shoulder-joint. This muscle is composed of three principal masses, which are attached as follows :

1. To the collar bone.

2. To the socket of the upper arm bone.

3. To the bladebone.

The three masses of which this muscle is composed incline downward and form a point, which is inserted into the middle of the upper arm bone.

This muscle has a threefold purpose; it can raise the arm sidewise, forward, or backward.

The muscle forming the breast is attached to the collar bone, to the inner half of the breastbone, and to several of the ribs. This muscle is called into play in the act of shrugging the shoulders.

What is called the mesial line begins in the hollow in the center of the collar bones and proceeds down the breastbone to the end of the trunk. The muscles of the chest cause, by their prominence on either side, a groove which plainly marks the upper half of the mesial line.

A depression of lozenge shape, at the bottom of the breastbone, is the result of a projection of cartilage from the seventh rib on either side.

A man's nipple is usually at the fifth rib, or just above it.

A continuation of the mesial line is caused by long straight muscles on either side of it, descending from the breastbone and forming the shape of the abdomen. Besides being attached to the breastbone, these muscles connect with the fifth, sixth, and seventh ribs. In action they pull the body forward and downward, causing numerous folds in the skin. Over them, at either side, extend bands which unite at their ends with the expanding tendons of a neighboring muscle. These bands are usually three in number, but are different in quantity and position in everybody.

Adjoining the muscle just considered, and descending obliquely in a beautiful curve, is another important muscle which joins, at its lower end, the pelvis, and, at its upper extremities, seven, or sometimes eight, lower ribs. It thus forms a regular, slanting, serrated pattern.

MUSCULAR DEVELOPMENT OF THE UPPER HALF OF THE FIGURE (Front).

Joining this and fitting into its saw-like edges is another muscle at the extreme right or left of the figure. Its tendons reach to the outer sides of the ten upper ribs and to the bladebone. A very large, broad muscle of the back is one that covers the portion below the bladebone. It is attached to the bones of the spine, from the sixth rib downward. From thence it extends forward and upward to the head of the upper arm bone, where it inserts itself in the shape of a thin and very strong tendon. This muscle draws the bladebone and upper arm backward and downward. It thus causes the bladebone to move upon the ribs. Underneath this muscle is another fleshier one attached to the pelvis, the angles of the ribs, and all the bones of the column. This muscle bends the body backward and, in doing so, produces many transverse wrinkles.

To state that the arm and hand of man give him powers which no other animal possesses is to put in words a self-evident fact. In accordance with their important mission these members have a wonderful and delicate mechanism. The human hand can reach every part of the exterior of the body, and it would be futile to attempt to indicate here the varied uses to which this extremity can be put, either alone or in connection with other members.

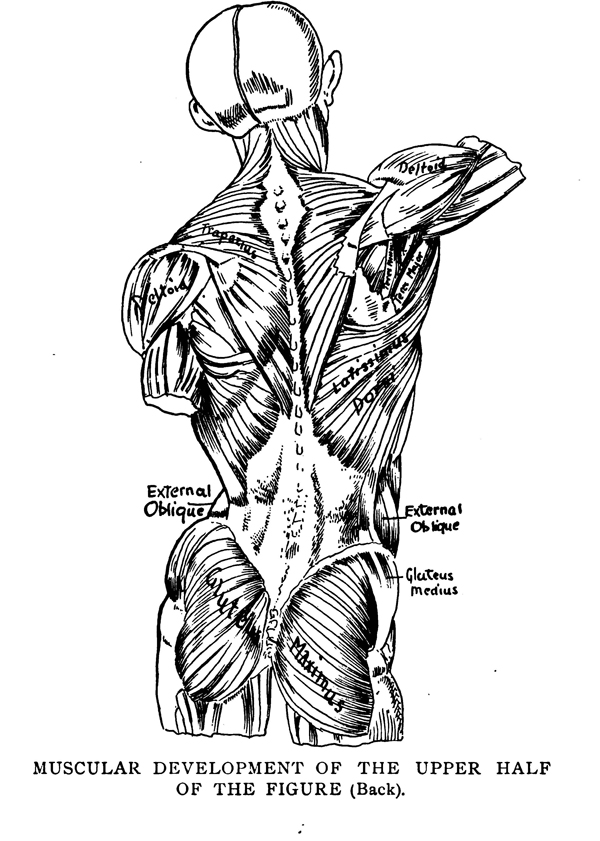

MUSCULAR DEVELOPMENT OF THE UPPER HALF OF THE FIGURE (Back).

One radical difference between the action of the upper and lower extremities is the manner in which the outer bone of the lower arm rolls over and across its neighbor. For this reason its joint is constructed in a radically different manner from that of the knee. When the bones of the lower arm are crossed, the palm turns backward and the thumb is toward the body. When this action is reversed the palm of the hand is turned forward and the thumb outward. The greatest mass of the hand is on the thumb side. The back of this important member is arched sidewise, the palm being concave accordingly. The knuckle of the middle finger is the most pronounced—though in a very plump woman or child the knuckles become indentations instead of projections. There are two principal sets of muscles which, in turn, cause the bones of the forearm to cross or resume their normal position.

Another set of muscles causes the arm to bend; still another set causes it to extend; the former being principally in front, the others in the back. In many cases these two sets of muscles act jointly. The muscles which cause the arm to extend terminate in the hand in tendons of a fan-like shape, which may be readily seen through the skin of a thin hand. When the fingers are bent inward they all have an inclination toward the center of the palm.

The elbow fits into the hollow of the upper arm bone. When the lower arm, to which it is attached, is straightened, the muscle of the arm—previously described as a triangle or Greek letter D—covers the biceps, which is formed of two heads, as its name indicates. Both of these heads are attached to the bladebone; they are quite fleshy at their principal point of size, but soon become tendonous after attaching themselves to the outer bone of the lower arm. They end in a sinewy membrane which descends along the forearm to the wrist. This muscle contracts appreciably at its fleshy part during strong action.

MUSCLES OF THE LEG.

The triceps is on both sides of the biceps. Extending around the back of the upper arm bone the triceps is divided into three parts so distinct that many consider them as three muscles. This triple muscle has the power of extending the forearm. The manner in which the principal veins of the arms are placed can be seen in a glance at the plate on page 73. Veins, if drawn at all, should be introduced in the most careful manner and should never be exaggeiated in the slightest degree. The muscles of the legs are generally united with each other in their various functions, and are intimately joined in fabric also. The limits of a work like the present do not permit the complicated descriptions which an involved subject of this sort require. The reader is, therefore, referred to the tabulated plates of the muscles of the leg and thigh given in this chapter.

It is desirable, however, to give some detailed attention to the knee-joint, as an important and beautiful part of the human form. The triceps, though thus named, consists of four distinct muscles according to some authorities; they unite to move the thigh inwards. One large muscle pulls the thigh upwards, another downwards.

The sartorius is said to derive its name, from the fact that it brings the legs obliquely across in the way tailors sit at work. It arises from the back of the pelvis—at first tendonous, then becoming fleshy—descends and inclines more inward, passes obliquely over the triceps, descends (again tendonous) to its insertion into the fore part of the shinbone. An important muscle, constituting the front of the thigh, arises, partly fleshy, partly tendonous, from the lower part of the pelvis and, running straight downward, fixes itself by a strong tendon into the kneecap. The kneecap being movable, there is of course a strong ligament attached to its lower point. This ligament is firmly rooted into a tubercle on the fore and upper part of the shinbone. Thus the extension of the leg is effected, as if the muscle itself were attached at this spot. A muscle (chiefly observable near its origin at the fore part of the spine of the pelvis) descends obliquely outwards; soon spreading itself and becoming tendonous, envelops another series of muscles. Thence it extends itself to the inside of the knee, which it envelops. It finally inserts itself in the head of the large bone of the lower leg. From thence it sends down an expansion to the foot.

A muscle having its origin at the front and top of the thigh-bone, and descending—with oblique fibers —in a large fleshy mass, is inserted into the inner side of the kneecap. Thence it throws off a system of fibers to the muscles of the lower leg. Next may be noted a muscle which, from its origin in the appendage of the large bone of the lower leg, runs down the outside of that bone rather obliquely, and is inserted into a large wedge-shaped bone adjoining the great toe. It bends the foot upward. A mass of muscle, made up of four lobes or heads, takes its rise from the two protuberances of the thighbone, at the back of the knee. Descending, it divides into two fleshy masses, commonly termed the calf of the leg.

A portion of this system of muscles also arises from the back parts of the bones of the lower leg, and assumes different degrees of flatness, according to the purpose for which the different units are intended. Where the strong tendon, common to these muscles, attaches itself to the heel-bone, there is a marked protuberance which should never be omitted in a drawing. The tremendous power of these combined masses of muscle and tendon is called into play by such actions as walking, running, and leaping. A long fibrous muscle, which runs down the outer side of the leg, is attached to the upper outer side of the small lower leg bone. From there it passes, tendonous, through the channel at the outer ankle, whence it inserts itself into the upper part of the principal bone of the great toe ; its most important use is to move the foot outward.

A tendonous, fleshy muscle arises out of the upper, outer part of the lower leg bones. It splits into round tendons and is inserted by a flat tendon into the root of the first joint of each of the four small toes; then it expands over the upper side of the toes as far as the root of the last joint. It has the power of extending all the joints of the four small toes. Another muscle arises, fleshy, from the inside of the root of the protuberance of the heel-bone and is inserted into the root of the first joint of the great toe. Its purpose is to pull the great toe from the others. When the knee is bent, the kneecap recedes partly into the space formed by the separation at the joint of the thigh and lower leg-bones.

Privacy Policy .... Contact Us