Home > Directory of Drawing Lesson > Human Face > Drawing the Neck, Throat, and Shoulders

Drawing the Human Neck, Throat, and Shoulders with Anatomical Pictures

|

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

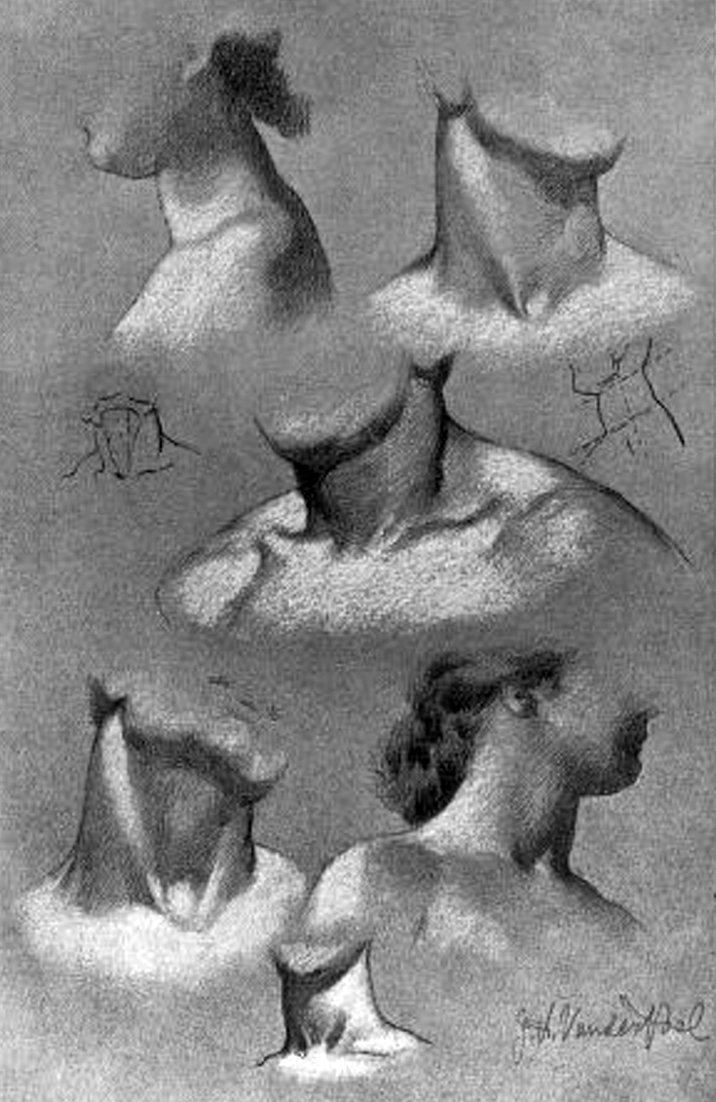

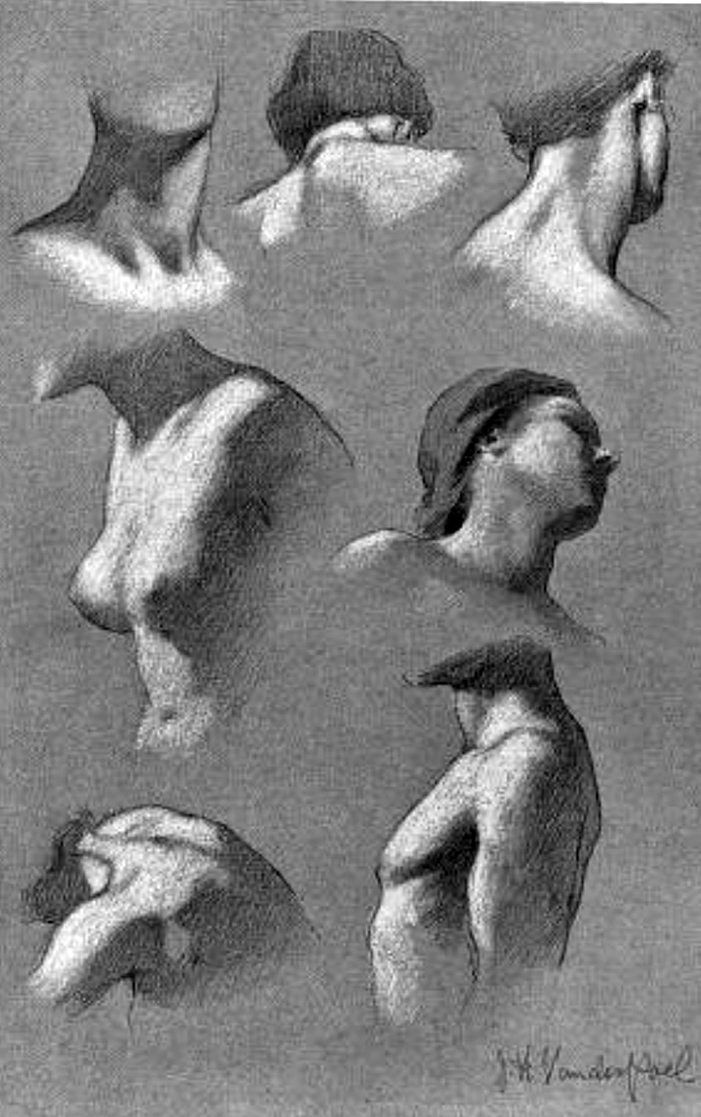

The neck, having much to do with the carriage of the head, should receive careful consideration. The neck is cylindrical in form, tapering slightly from its base up. As the base of the skull is higher at the back than at the jaw, and the pit of the throat above the clavicles lower than the base of the neck in the back on a line with the vertebral prominence, it is discovered that two parallel lines sloping downward from back to front mark the upper and lower extremities of the neck. A line nearly at a right angle to these parallel lines denotes the forward direction of the throat ; this forward tendency, however, is greater in the female than the male. In the male, too, the sections would disclose a tendency to flatter planes than in the more cylindrical form in the female. In the male, too, the larynx or Adam's apple is more conspicuously marked.

In case of a front view, the sides of the neck are symmetrical;

that is, structurally, when in action, as in throwing the head well to

the side, though the evidence of structural symmetry remains, the lines

inclosing the form become radically different. In the profile, however, the line that incloses the neck at the back differs radically from

its opposite at the throat, both in its elevation and its nature. In the

study of the construction of the human figure, the student should learn

early that all parts of the figure, irrespective of their distinct nature in bony or muscular structure, interlace as they fuse into the other. In the skeleton the parts are distinct, yet they connect with mathematical precision ; the muscles are distinct in form and function, but

it requires a trained mind and eye to trace their origin and termination as they fuse one into the other. In the living model the

continuous skin envelops the complete structure, and creates planes

that embrace both bone and muscle — parts of the planes that bound

one form interlace with portions of 'planes that bound another. For

example, the upper part of the neck reaches well up into the back of

the head, and is much higher than the junction of throat and jaw, the

back of the shoulders is higher than the base of the throat, and again

the deltoid that clothes the shoulder like an epaulet, enveloping

the outer end of the clavicle, the spine of the scapula, and the head of

the humerus, marks the breadth of the shoulders, though from its

apex to the elbow it measures the length of the upper arm ; the

biceps in its descent penetrates the forearm, whilst the mass of muscle

on the outer side of the forearm, the supinater longus, enters the upper

arm. The trapezius produces the flat plane of the nape of the neck, the sides are diagonally crossed by the sterno-cleitla mastoid, beginning at the lateral borders of the base of the skull, inclosing between

them in their descent the larynx and the pit of the neck, terminating

along the upper border of the clavicles.

The plane of the nape of the neck is only broken at its connection with the skull by the slightly outward sloping surface of its base, the sides of the skull back of ear fuse almost imperceptibly into the lateral planes of the neck; at the angle of the jaw we find the least fusion, the angle of demarkation being strongly accented, particularly in the male, the front of the throat, by means of the upper part of the larynx, penetrates the under surface of the jaw, coming forward into it. This is particularly noticeable when the head is thrown back. The base of the neck at the back is buttressed on both sides by the trapezius, elevating the plane from which the neck issues above the forward base just within the clavicles. The grace of the female neck as compared with the firmness of the male should be noted.